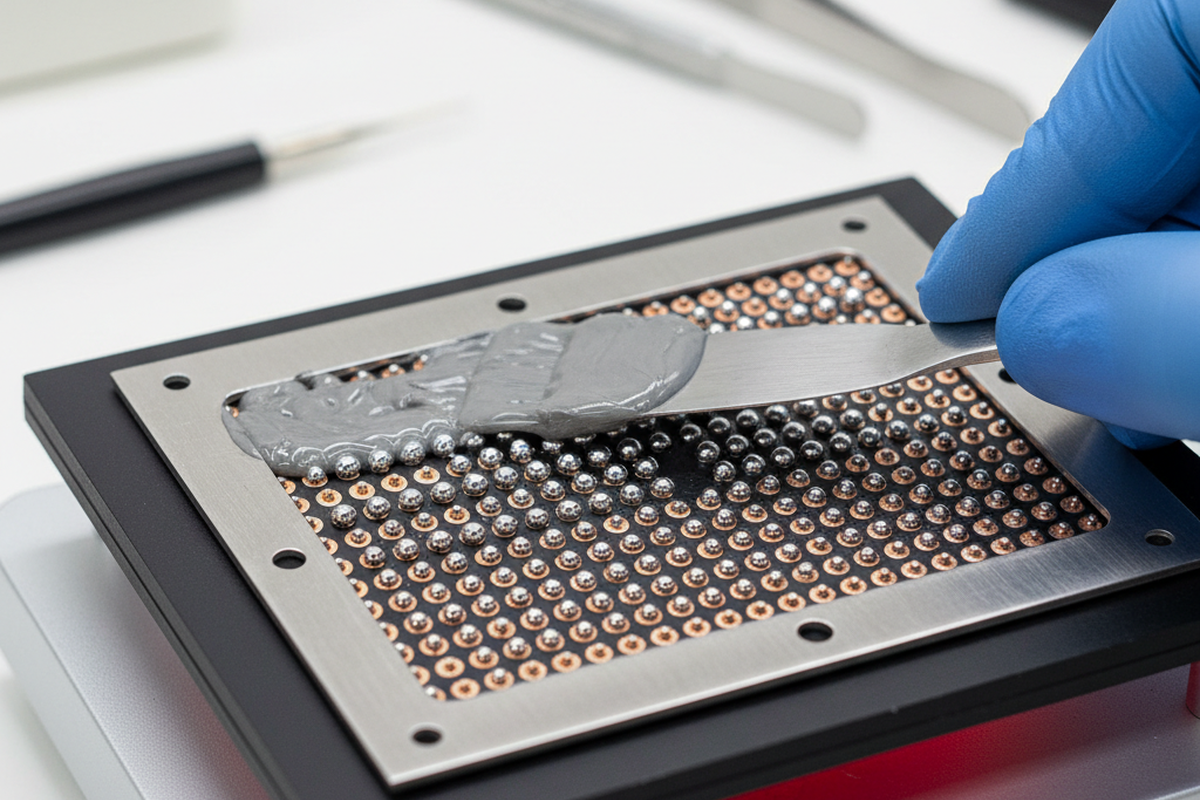

A BGA reball often looks like a clean win: shiny balls, no bridges, board boots, quick functional test passes, invoice paid. That’s the version people want.

Then the unit comes back.

In late 2017, on a depot floor in Cedar Rapids, IA, a reballed edge router shipped with a traveler labeled RWK-17-0932. It passed every check that mattered to throughput. Six weeks later it returned under what would become a recurring warranty tag, REB-RTN-30, showing the same intermittent symptom plus a new one. The deeper finding wasn’t bad solder balls. It was a board flex issue near a mounting point and early pad cratering that the reball didn’t fix—and the extra thermal cycles actively worsened.

That return exposes the trapdoor in this entire category of work: a reball can create the appearance of success while pushing a marginal board closer to irrecoverable.

A shop can still decide to reball—Kline certainly does. But she treats it like a controlled mechanical intervention with gates, artifacts, and a written risk boundary, not a premium default repair.

Stop Conditions Before Heat

Stop. Don’t heat it yet.

Kline’s gate-first triage starts before any station warms up because the most expensive failures in BGA work are the ones created by unnecessary heat cycles. Her NPI visit in Sioux Falls, SD (run sheet R3) produced a set of boring-looking controls: an explicit rework cycle cap (set to 1 for that assembly), a thermocouple map (center + four corners + a nearby polymer connector), and an X-ray checklist added to the traveler. She didn’t add these to slow rework down. She added them to stop rework from becoming the default path for every ambiguous fault.

A common inbound question is “should it be reflowed or reballed?” That question is already off by one. There’s a third option that saves more boards than either: don’t touch the BGA until there is evidence the mechanism is joint-related. Kline’s 2022 depot KPI review included a painful reminder—roughly 28% of “no video” boards arriving with “reball requested” paperwork ultimately had VRM or shorted MLCC issues. Reballing them first wasted 1.5–2.0 labor hours per unit and added heat history that complicated later diagnosis. A shop can’t afford to treat “reball vs reflow” like a menu choice when the real decision is “touch the package vs prove the failure mode.”

There are also hard stop conditions where a reball isn’t just “high risk”—it is predictable damage. Underfill is one of them. In winter 2020, Kline inspected underfilled BGAs under UV and ran a controlled removal on a sacrificial board. The underfill bonded to the mask and tugged at pads during lift. That lesson turned into a policy note: UF-BGA: decline unless FA-only. This was in response to a broker demanding a 48-hour SLA and treating the job like a routine GPU reball. Kline’s decision wasn’t philosophical; she simply recognized the board would be ruined before new spheres ever touched it.

The last gate is documentation discipline. In her world, “we tried” is not a service output; a traveler with acceptance criteria is. Without written stop conditions—underfill present, visible warpage, unknown prior rework count, contamination that can’t be removed—rework decisions drift to whoever is most confident with hot air. That is rarely the same as whoever is most correct.

Pad Health Is the Real Go/No-Go (Not Removal Skill)

If a customer says “the pads look fine,” Kline hears “the pads look fine at the magnification and attention span we used.”

Her training day in spring 2024 focused entirely on that bias. Two junior techs sat under a microscope with an HDMI camera feed to a monitor, tasked with writing a go/no-go decision on a worksheet labeled GO-NOGO-RWK v2. The boards weren’t dramatic: one clean site, one with subtle solder mask disturbance, one with early cratering that looked like “nothing” at low magnification. The uncomfortable reveal came later—continuity checks logged per net didn’t agree with the confident visual call. That lesson resurfaces when a board passes functional test and still becomes a return: pad adhesion and inner-layer integrity aren’t visible just because the copper is still “there.”

The 2017 return story stops being a cautionary anecdote here and becomes a decision rule. A board with a flex-driven failure near a mounting point can present like a BGA intermittency because stress concentrates at corners—exactly where pad cratering shows up first. Reballing can temporarily change contact behavior enough to “fix” it at room temperature while the underlying pad-to-laminate bond degrades. When the board goes back into service and sees thermal cycling and mechanical stress again, the new solder joints are only as good as the pads they sit on. A “successful” reball effectively converts a marginal board into a latent failure.

So the minimum evidence set for pad health must be more than “looks clean.” Kline’s gate is blunt: if pad integrity can’t be verified, the job is classified as unknown risk and defaults conservative. In practice, this means at least one of the following is required before a reball counts as responsible service work: high-magnification inspection for mask disturbance and corner anomalies, continuity/resistance checks that are logged (not waved at), and a corroborating artifact such as pre/post X-ray context or a documented symptom change under controlled stress. The exact tools vary from shop to shop, but the decision must be anchored to something other than optimism.

Kline rejects the framing that rework skill is mainly about getting the chip off and back on. Removal dexterity matters, of course. But the decision to proceed is the craft that determines whether the board leaves as a stabilized repair or a time bomb.

When Reballing Actually Helps (Mechanisms, Not Myths)

Kline isn’t anti-reball. She’s anti-blind-reball.

Mechanism trace is the filter. If the symptom is intermittent and correlates with temperature or mechanical flex, joint fatigue or head-in-pillow is plausible. If the symptom is a dead short or rail collapse, the highest-probability culprits in her logs are often not the BGA at all—shorted MLCCs, PMIC faults, or VRM damage that a reflow temporarily “heals” by changing contact resistance. She deals in likelihoods, not certainties. Symptom lists without evidence are just marketing.

Her 2021 case at a third-party X-ray lab in Minneapolis, MN, is the cleanest example of reballing justified by mechanism and then validated. A board passed ICT and a quick functional test after reball; the straight-on X-ray looked acceptable enough to a tired operator. The NDT tech rotated to an oblique angle and the signature changed—an incomplete wetting pattern consistent with head-in-pillow risk. Kline held shipment, revised the profile (increased soak and adjusted ramp), and the second X-ray showed a materially different wetting signature. The customer email subject later made the point more clearly than any lecture: HIP suspicion confirmed.

This sequence matters because it shows the conditions under which reballing is the right call: evidence points to a joint-related failure mode, and the shop has a way to verify the outcome beyond “it boots.”

The “reflow or reball?” question comes back here, too. Again, the useful answer isn’t definitional. Reflow without diagnosing the mechanism is often just adding an uncontrolled heat cycle. Reball without verifying pad health is often just adding a controlled heat cycle. The third option—prove the mechanism with artifacts—determines whether either thermal event is justified.

X-ray Is a Gate, Not a Photo-Op

The phrase “X-rayed” has become a marketing badge. Kline treats it as a gate with limits, not a stamp.

Her house rule since 2019 is simple to describe and annoying to enforce: no BGA rework release without documented pre/post comparison and a voiding callout, tracked internally under XR-GATE. That rule didn’t come from a standards committee. It came from returns and disputes, and it reportedly reduced 60-day returns on reworked units by about 35% in the first year of enforcement. The practical reason is obvious: a single post-rework image can look “fine” without proving improvement, and a straight-on view misses patterns that only show up at an angle.

We need to correct the “X-ray as checkbox” confusion. A customer asking “do I need X-ray after reball?” is usually trying to buy certainty. Kline’s answer is that X-ray can show geometry, gross defects, and patterns that correlate with risk, but it cannot prove metallurgy or pad adhesion. It is helpful because it is comparative and contextual: straight-on plus oblique, pre versus post, and interpreted with an acceptance boundary that is written down.

Acceptance boundaries aren’t a single magic voiding percentage. Kline refuses to give a universal number because it’s not honest. The risk of voiding depends on ball function (power/ground/thermal vs signal), package geometry and pitch, and the customer’s reliability horizon. Voids clustered in a way that suggests incomplete wetting, or voiding concentrated on power/ground balls that carry heat and current, are treated differently than small, distributed voids on low-stress signals. In her writing and training, the rule is: if the shop cannot articulate why a given pattern is acceptable for this board and this use case, then it isn’t an acceptance criterion—it’s a vibe.

And there are “X-ray is not enough” cases that need to be said out loud. If pad cratering is suspected, inner-layer damage is plausible (thick multilayer, heavy copper, prior aggressive profiles), or the board is safety-critical, X-ray alone is weak comfort. In those cases, Kline pushes toward deeper inspection (up to and including microsection in some environments) or declines the rework for production deployment. That stance is unpopular with buyers who want a single binary test. It is also how a shop avoids shipping boards that become the next REB-RTN-30.

Thermal Profiles: Respect the Stackup or Accept the Damage

A universal rework profile is malpractice with good intentions.

Kline doesn’t answer “what temperature for a reball?” with numbers. She answers with board classification and measurement requirements. Thickness, copper density, nearby shields, local heat sinks, and the distance to collateral-risk plastics are the variables that control gradients and warpage. If those are unknown, the risk is not “maybe,” it’s “higher than the quote assumes.”

Her 2016 incident demonstrates the kind of damage that makes this point stick. At a depot station using an IR top heater with a bottom preheater, she profiled for BGA center and ignored a plastic mezzanine connector roughly 25 mm from the package edge. The board came off looking fine. Later, the connector was found slightly deformed, and the failure presented as intermittent contact. The postmortem lived in the binder as COLL-2016-04, and the corrective action was boring: build a thermocouple map that includes “innocent bystanders,” and keep it with the profile notes. Even the choice of attachment method mattered in practice (Kapton tape versus high-temp epoxy), because thermocouples that lie to the operator are a different kind of hazard.

Throughput myths get people hurt here, specifically the belief that higher heat is safer because it reduces dwell. Kline’s counter is that faster profiles often increase gradients, and gradients are what warp boards, stress via-in-pad structures, and cook nearby connectors. Her profile library labels—6L-mid copper, 10L-heavy copper, RF-shield dense—remind the operator that the board class is the unit of planning, not the package.

A shop that wants to be responsible without publishing proprietary OEM recipes can still be specific. The minimum profiling checklist she insists on is stackup-aware: instrument center and corners, instrument at least one collateral component (often a connector), tune preheat/soak to reduce deltas before chasing peak, and document ramp rates and maximum delta across points. If a shop cannot measure those basics, the honest response is not “we’ll be careful,” it is “we cannot prove control.” That changes whether the job should be taken at all.

Service Rules in Writing: A Practical Gate Checklist (and When to Scrap)

At the end of Kline’s framework, the “service” part matters as much as the “rework” part. The output is more than a booting board—it’s a defensible recommendation for when the unit fails again in the field.

She uses memo language with decision-makers for this reason. The 2023 grain facility example is clean: an industrial drive control board (thick, conformal coat, heavy copper) failed intermittently, and the maintenance lead wanted a BGA reball because “we’ve fixed boards like this before.” Kline redirected to operational math: downtime in $/hour, probability of success, lead time for replacement, and the safety cost of a latent failure inside a control loop. In that case, replacement beat rework and everyone was happier because the decision was made in the right units.

A practical gate checklist for BGA rework services looks like this when it’s written to prevent arguments later:

- Define consequences: uptime impact, warranty liability, safety exposure, and whether the board goes back to production or only to failure analysis.

- Hard stops (scrap/decline unless FA-only): underfill present (

UF-BGApolicy class), visible warpage, unknown or excessive prior rework cycles, contamination that cannot be removed, missing/damaged pads beyond what can be repaired with acceptable reliability, or assemblies where qualification and sign-off are not available. - Mechanism hypothesis: state the most likely failure mode (joint fatigue, HIP risk, flex-driven intermittency, inner-layer damage, non-BGA rail fault) and what evidence would falsify it.

- Minimum artifacts before release: logged resistance/continuity checks on relevant nets, documented thermocouple map and profile notes, and X-ray comparison where applicable (

XR-GATE: pre/post, straight-on + oblique). - Acceptance criteria: contextual boundaries (no single voiding percentage), plus explicit “cannot prove” statements (pad adhesion, metallurgy, field-life equivalence).

- Validation tier: minimum viable checks (extended run and symptom reproduction attempt) versus stronger checks (thermal stress screening, controlled flex checks) depending on consequence of failure.

The “it boots” problem still has to be said plainly, because it keeps showing up as an endpoint. “It boots” is a snapshot. Reliability is a time horizon. The 2017 router return makes the failure mode obvious: a board can pass room-temperature functional test and still fail under thermal cycling or mechanical stress, especially when the underlying mechanism is pad cratering or flex. Kline’s rule is to red-team success: describe the plausible near-term pass and the plausible long-term fail, then decide whether the customer’s use case tolerates that probability. Validation doesn’t need to imitate field life, but it must be honest about what it is and isn’t proving.

The cost question—“is reball worth it?”—is where shops accidentally become salesy or evasive. Kline avoids this trap by using expected-cost framing rather than a simple price table. If the board is low value, or replacement is available quickly, and downtime cost is modest, a risky reball attempt is often irrational even when it is cheaper than replacement on paper. If the board is high value, replacement is EOL, or the organization explicitly accepts reduced reliability for learning (failure analysis), a reball can be rational—if the gates are met and the risk is signed off. That’s the difference between a service recommendation and a heroic story.

Scrap triggers are the uncomfortable part, and they belong near the top of any service rules document because they save the most time and boards. Underfill that bonds aggressively, a board with multiple prior heat cycles, visible warpage, or evidence that pad adhesion is compromised are not “challenging jobs.” They are jobs that pay once and cost twice when the callback arrives. Kline’s own receipts are why she’s strict: REB-RTN-30 exists because “send it” decisions were made without pad verification and without comparative acceptance artifacts.

There’s also a limit statement that should appear in any competent write-up: X-ray is helpful, but not omniscient. The Minneapolis oblique-view case demonstrates both the value and the limit. It caught a wetting-risk pattern that a straight-on view would have missed, and it justified a profile revision. It did not prove pad adhesion, it did not prove metallurgy, and it did not promise field life. It’s scope control, not pessimism.

FAQ (Short, Because the Gates Are the Point)

“Can a shop reball without X-ray?”

Yes, but it becomes a different service category. Without pre/post and angle-aware imaging (internal XR-GATE style), the shop leans harder on process discipline and electrical evidence, and acceptance thresholds should tighten. For high-consequence boards, “no X-ray” often means “decline or FA-only.”

“What voiding percentage is acceptable?” A single percentage is the wrong promise. Acceptance depends on ball function (power/ground/thermal versus signal), package geometry, and customer reliability horizon. A shop should be able to point to location and pattern risk, not just “looks normal.”

“Why not just reflow first?” Because reflow is still a heat cycle that can warp a board, disturb mask, and push marginal pads toward failure. If the mechanism isn’t joint-related, it’s wasted risk. The third option—prove the mechanism—is usually the cheaper move.

“How does a customer know they’re not being sold a ‘premium’ reball?” Look for artifacts: a written stop-condition list, a rework cycle cap, a thermocouple map and profile notes, and comparative imaging or logged measurements. “No fix no fee” can be a business model; it is not evidence of controlled risk.

“When is ‘scrap now’ the best technical recommendation?” When the cost of a latent failure is high (safety, warranty, downstream damage), when the board history is unknown but likely harsh, and when pad integrity cannot be verified. In Kline’s framework, “scrap” is not an insult; it’s a controlled decision boundary that prevents repeated downtime and cascading losses.

The most consistent through-line in Kline’s service rules is that refusing work is sometimes the most responsible output. Her 2019 shift to writing scrap criteria into the traveler wasn’t about being conservative for sport; it was about turning “what can be done” into “what should be done,” with receipts, gates, and limits that survive the next dispute.