A pilot run can look stable right up until it doesn’t. One day the line produces clean boards, AOI looks calm, and everyone talks like the hard part is over. The next day, the same program yields bridges and opens like someone flipped a switch. The uncomfortable part is that nothing “big” changed—just the normal things that happen on a Tuesday night with a mixed crew.

In one Brooklyn Park pilot line build, the drift showed up in a place people didn’t want to stare at: solder paste volume trending down across a region. Koh Young SPI made it obvious once someone bothered to look at the trend instead of the pass/fail snapshot. And then it got worse: a reflow recipe on a Heller 1809 had been nudged midstream because someone was “tuning for shine.” This isn’t sabotage. It’s just what happens when there’s no agreed definition of “same build.”

When schedule pressure hits, the natural request is usually “can we add more test” or “can we put more inspection on it.” While that request makes emotional sense, it targets the wrong deliverable. A pilot’s job isn’t to prove the team can muscle units out of the line once. It exists to prove the process is repeatable under normal variation, with the knobs controlled and captured.

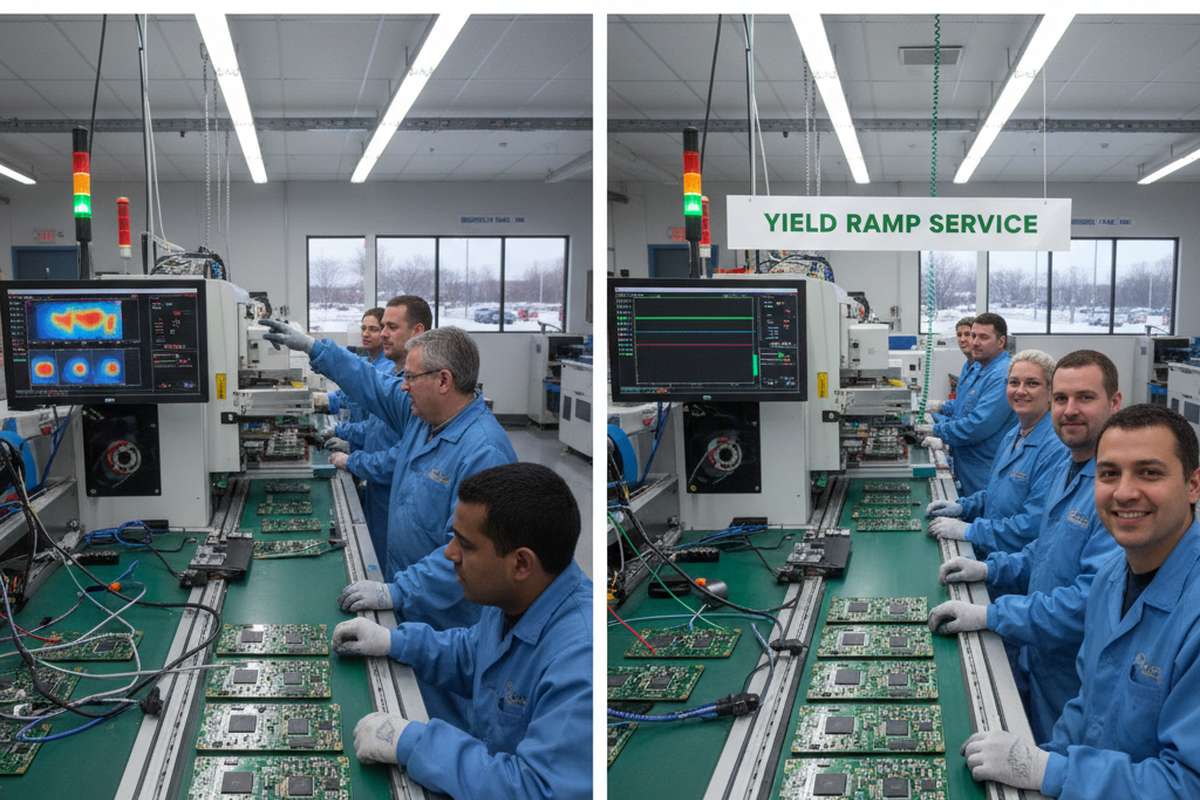

What Yield Ramp Service Actually Is (and what it isn’t)

Yield ramp service, done well, runs on two tracks simultaneously. The first is containment: protecting shipping and safety while the rate is still ugly. The second is capability: closing the defect mechanisms so the line stops needing heroics. Teams under pressure often do only the first track and then call it “ramping.”

The “add inspection” reflex is the easiest place to see the failure. Adding AOI coverage or expanding functional test can reduce escapes in the short term—and in regulated products, that containment is mandatory. But inspection does not make the process more stable. Worse, unmanaged inspection can make the factory socially numb: operators learn which calls are noise, auto-disposition half of them, and the defect data turns into a pile of arguments. That happened on a Mirtec AOI program where connector shadowing created constant nuisance calls. The line had “lots of defects” on paper, but very little clarity in reality. Inspection systems fail socially before they fail technically.

You don’t have a yield problem; you have an uncontrolled process problem.

This matters financially and operationally, not just philosophically. If a board takes 14 minutes of touch-up at a rework bench and the burdened rate is $55/hr, that’s about $6.40 per board in labor before retest time, scrap risk, and the hidden cost of queues. That number isn’t rare; it shows up whenever teams normalize rework as the plan. The yield number can still look “fine” if the organization only counts what ships.

This confusion is constant, so let’s clarify: FPY is first-pass yield through a defined step without rework. RTY is rolled throughput yield across steps. “Shipped yield” is whatever is left after enough people touch it until it passes. Teams love the last number because it makes slide decks feel safe, but it makes margins imaginary. A reasonable FPY target isn’t universal; it depends on unit economics and risk. A high-mix industrial control might live with 92% FPY for a while if rework is bounded and documented. A tight-margin, higher-volume product can’t, and the math will punish it.

So the service isn’t just “more inspection.” It is a time-boxed containment plan paired with a root-cause closure plan forced to produce a stable baseline. A common forcing rule is simple: containment is allowed for one or two builds while the top mechanisms are being falsified and closed. If containment becomes indefinite, the organization is renting output.

The First Forcing Function: A Defect Pareto That Doesn’t Lie

Ramp chaos makes everything feel equally urgent, which is how teams burn weeks. The antidote is a defect log that can survive scrutiny and a Pareto that makes it hard to argue.

The minimum requirement is boring: a consistent taxonomy and enough columns to connect defects to mechanisms. It does not have to be a perfect MES, but it has to be usable. The moment a team cannot answer “where, on what refdes, on which line, at what time,” they’re doing storytelling, not yield work.

A defect log that supports a real Pareto needs, at minimum:

- Defect type (consistent categories; IPC-7912A-style categories are fine if the team can actually use them)

- Location and refdes (not just “side A”)

- Time/date and build/lot identifier (so drift shows up)

- Line/machine and operator/shift (because variation has fingerprints)

- Disposition and rework steps (so rework isn’t invisible labor)

From there, the move is ruthless: circle the top one to three defect modes and trace each mechanism across the flow—material → print → place → reflow → inspect → test → handling. Not every defect deserves equal engineering time. Prioritizing isn’t callous; it’s how ramps survive. There is one exception that must be said out loud: a low-frequency defect that is catastrophic (safety, regulatory, recall-level) gets elevated above its Pareto rank. That is simply risk management with a spine.

The Pareto also depends on inspection credibility. If AOI is generating 40% nuisance calls, the Pareto is polluted and the team will chase ghosts. That’s why “tuning AOI” is not a nice-to-have. On that Mirtec line, a simple governance rule changed everything: any repeated nuisance call gets fixed within 48 hours or it gets removed. That rule restored trust, cleaned the defect data, and allowed the real top defects to surface—insufficient solder on a QFN corner and a rotated 0402 tied to a feeder lane issue. Cleaning the measurement system is part of yield ramp work, not an afterthought.

Paste Is Where Pilots Quietly Die (Stencil + Print Control)

A lot of teams want a magical answer here: “What stencil thickness should we use?” “What aperture reduction is recommended?” “What’s the best reflow profile for SAC305?” That’s recipe hunting. It is seductive because it sounds like certainty. In pilot, the deliverable isn’t a static recipe. It is a process window and the controls that keep the process inside it.

Paste printing is the most common place where a pilot’s stability story falls apart. It’s also a place where small, fast changes can move yield more than large, slow ones. In a build where a BGA corner open showed up intermittently, the easy narrative was to blame the BGA supplier. The uncomfortable move was to ask for SPI time-series data and look for drift over an hour of printing. That data showed paste volume variability increasing over time, especially on perimeter pads. X-ray (a Nordson Dage-like system) confirmed the symptom at the BGA corner, but SPI pointed at the mechanism.

The fixes were not glamorous: a quick-turn stencil modification, a tighter under-stencil wipe cadence, and a defined squeegee pressure window. These aren’t “forever answers” in isolation; they are controllable knobs that can be put into a stable window. They also produce evidence. Evidence matters because it prevents the team from escalating to suppliers based on vibes. Prove internal print capability first, then escalate externally if the defect persists under controlled conditions.

This is also where pilots get tricked by shift variation. The pilot can look stable on day shift with the most experienced printer operator and then slide on second shift when paste age, humidity, and operator technique are slightly different. The Brooklyn Park case looked like an operator problem until the defect log and SPI trends were aligned by time and location. Paste volume drift near a shield can region was measurable, and it correlated with a mid-shift change that wasn’t documented.

A short checklist of print controls that often belong in a pilot baseline:

- Paste type and handling rules (Type 4 SAC305 is not magic; it’s just a parameter that must be controlled)

- Under-stencil wipe solvent and cadence (and a rule for when it changes)

- Squeegee pressure and speed ranges (a range, not one number)

- Printer setup checks tied to shift change (because drift has predictable timing)

- SPI thresholds and data exports that show trends, not just pass/fail snapshots

This isn’t a full stencil design tutorial. IPC-7525 exists for a reason. The point is that yield ramp service treats paste and print as first-class yield levers and insists on controls that survive normal variation.

Reflow Profile: Stop Recipe Hunting, Build a Boring Window

Reflow profile work in pilot often fails because it gets treated like a cosmetic knob. Someone sees dull joints and “tunes” zones until the solder looks shinier. Someone else sees a void pattern and changes soak time without capturing it. Then the team tries to learn from defect data that was generated by a moving target.

One earlier-career lesson that shows up again and again is that boring windows scale. A “best setting” mindset tries to push the process to the edge: fastest conveyor, hottest peak, minimum paste to avoid bridges. That feels efficient until paste is an hour older, humidity shifts, boards warp slightly, and a different operator loads the printer. In a small DOE-style trial, changing a few knobs—wipe frequency, squeegee pressure, soak time—can reveal a wide window that is less pretty but far more repeatable. Pilot does not need the prettiest joints; it needs joints that are boringly consistent.

This is why the Heller 1809 recipe lock detail matters. The specific oven model is less important than the fact that the profile is an artifact with an owner, a version, and a record. If a profile change is needed, it gets logged, and the downstream data is labeled accordingly. That alone prevents half the “it ran fine yesterday” whiplash.

And yes, this is contextual. There is no universal “best reflow profile for SAC305,” because oven types differ, board mass differs, component density differs, and nitrogen vs air changes wetting behavior. The most honest output is guardrails and a method to find a stable window quickly, not a copy-pasted graph.

Once the team can say, without flinching, what the profile is and what range is acceptable, the next question becomes human: can the process survive shift-to-shift behavior? That’s where operator loops stop being “soft stuff” and become yield mechanics.

Operators, Inspection Credibility, and the 10‑Minute Loop

Operator feedback loops beat most dashboards during ramp because ramp problems are tactile and local. Paste behavior changes. Handling damage shows up around a fixture. AOI calls stop matching reality. If the line has learned to ignore its own inspection, the ramp is already in trouble.

On the line where AOI nuisance calls trained people to auto-disposition, the failure wasn’t that Mirtec was a bad machine. The failure was governance. Operators were clearing the same connector shadow call again and again, which is a predictable human response to repetitive noise. The fix was partly technical—lighting and library thresholds—and partly social: a visible rule that repeated nuisance calls get fixed within 48 hours or they get removed. That rule rebuilt credibility, cleaned the data, and made the Pareto honest.

A lightweight loop that works in pilot is a 10-minute end-of-shift debrief with three prompts: “What slowed you down?”, “What did you rework twice?”, “What did the instruction not match?” The key is closure: changes happen within a day or two, and the team explicitly connects “we changed X because you saw Y.” In regulated environments, that closure has to flow through ECO/NCR pathways and controlled work instruction updates. The loop still works; it just needs the right paperwork plumbing so “fixing the line” doesn’t become undocumented process drift.

Golden Process Packet: Making the Pilot Transferable (and CM‑Proof)

A pilot that cannot be replicated in another building is just a story, not evidence. That matters most when a product moves from an in-house line to a CM, or from a pilot crew to volume shifts, or from one geography to another. The failure mode is predictable: the “same rev” gets built under different consumables and different settings, defects change shape, and blame becomes the operating system.

In a medical pilot transfer between a customer site in Madison and a CM in Guadalajara, the boards were often electrically fine, but the lot reviews were chaos. People could not answer what changed. An oven zone had been tweaked. A stencil wipe solvent had been swapped. Nitrogen reflow had been used in one place and air in another without being captured. When BTC/QFN voiding and intermittent opens appeared at the CM, it was tempting to frame it as “the CM can’t build it.” The actual defect was the missing baseline.

This is where yield ramp service becomes governance work. A “Golden Build Packet” is not a formality; it is the transfer vehicle. It defines what “same build” means in artifacts, not in intentions. It also creates a forcing function: if the team cannot write down the process, the team cannot claim it is stable.

A practical golden packet typically includes version-controlled, revision-matched items like:

- Stencil drawing and any step stencil callouts (including aperture notes)

- Oven recipe and how it was measured/validated (not just “Zone 3 = 240”)

- Placement program identifier or hash and machine setup notes

- AOI library version and inspection thresholds (and rules for nuisance calls)

- SPI thresholds and what data gets exported

- Work instructions, torque specs where relevant, ESD controls, and rework limits

- Change-control pathway: who can change what, with what evidence, and how it gets recorded

A detour that matters because people get stuck here: acceptance thresholds are not always universal. BTC/QFN void criteria, for example, can be application- and standard-dependent, and teams should not improvise that in the middle of transfer. The disciplined move is to agree criteria with quality/customer stakeholders and to record what standard revision or internal spec is being used. The point is not to turn the pilot into a paperwork festival. The point is to stop silent tweaks from turning pilot data into anecdotes.

The gate is blunt: do not scale until “same build” has a definition, and that definition lives in a packet that can travel.

Follow the Unit: When “Yield” Isn’t the Bottleneck Anymore

Even when SMT FPY improves, pilots can still miss shipment dates because the constraint moved. Yield ramp service that only stares at solder joints can miss the real blocker.

In a Penang CM build, the SMT line stabilized, but deliveries were still late. Following the unit revealed a queue at functional test, driven by a bed-of-nails fixture problem: intermittent contacts caused retests, which created more queue, which created schedule slip. The instinct was to buy more fixtures. The faster fix was to redesign contacts and establish a documented cleaning and maintenance cadence, recorded in the same golden packet that defined the SMT baseline. FPY barely changed, but throughput did—because the system constraint wasn’t solder anymore.

A simple litmus test closes the loop: containment is what keeps shipping risk contained this week. Capability is what makes next week calmer and cheaper. If the pilot ends with only containment—more test, more inspectors, more rework benches—output might exist, but the ramp is renting it. If the pilot ends with a Pareto-driven closure plan, a credible inspection system, a boring process window, and a golden packet that defines “same build,” the ramp has something that can actually be scaled.