A board can look clean. It can pass a bulk ionic number highlighted in green on a certificate. And it can still leak in the field.

This isn’t cynicism. It’s geometry, humidity, and time catching up with a measurement that looked in the wrong place.

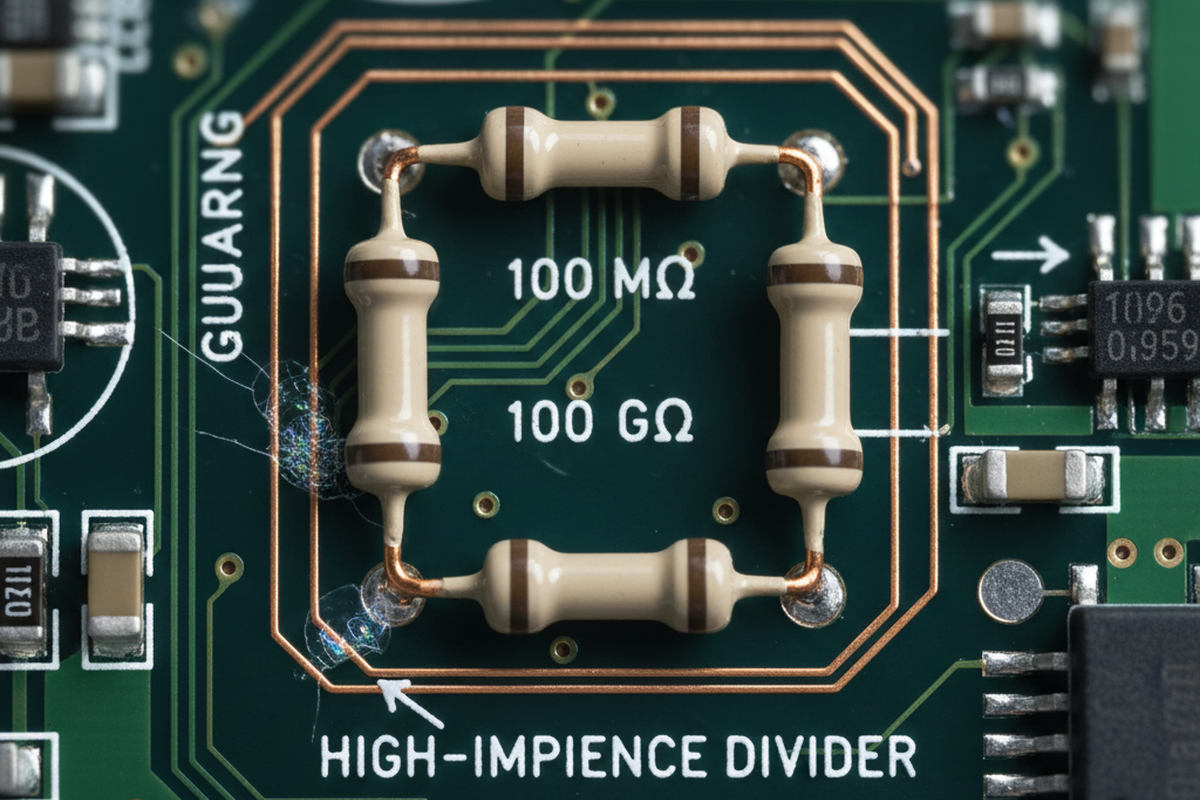

Consider a familiar pattern in industrial sensing: a platform with a high‑impedance divider (100 MΩ to 1 GΩ) behaves perfectly on the bench and passes incoming checks, yet starts showing offset drift after coastal deployment. The argument in the room is always the same: the contract manufacturer has a ROSE report; it meets a limit; it should be fine. Meanwhile, the only setup that reveals the drift is a biased humidity exposure—think 85%RH with bias applied across the sensitive network—where the failure appears slowly, like a timer.

When you section the failure down to a specific neighborhood (usually a low‑standoff LGA/QFN region near a guard ring), the “bulk clean” story falls apart. Localized extraction around the hotspot reveals contamination the whole‑board number never captured. The corrective actions that actually move the needle aren’t heroics. They are mundane disciplines: rinse resistivity trending, loading rules that prevent shadowing, and rework flux discipline enforced by a work instruction revision tied to an ECO.

Here, the shortcuts start to multiply: “Can’t we just conformal coat it?” “Can’t we just ask for a cleaner certificate?” “Can’t we just increase spacing?” These questions are comforting because they sound like closure. They aren’t.

A cleanliness certificate is input data. It is not evidence that a high‑impedance or high‑voltage surface will stay insulating across humidity, bias, and aging.

Real evidence looks different: mechanism‑linked validation that matches the failure mode, plus process controls that make cleaning outcomes reproducible—including the parts of manufacturing everyone wishes didn’t count, like rework and selective solder touch‑up.

What “Clean” Means When Nanoamps Matter

For high‑impedance and HV assemblies, “clean enough” cannot simply mean “we extracted ions from a big area and the number was below a limit.” The goal is narrower and more demanding: prevent leakage drift and insulation degradation across seasons, storage profiles, and time under bias. This is an electrical reliability goal, distinct from cosmetic standards. A thin, patchy residue film that would never trigger an alarm on visual inspection can become electrically active in humidity. Once bias is applied, it stops being a passive contaminant and becomes part of a conduction path.

Mechanistically, the ingredients are simple: ionic residue, moisture, bias, time, and geometry that lets a film bridge what spacing diagrams assumed would be air. The hard part is that the geometry you care about is often hidden. Under‑component zones—QFNs, LGAs, BGAs, tight‑pitch pins, and the edges of adhesives or staking—are where residues get trapped and where wash reach is worst. These are also the exact places teams can’t inspect well, and exactly where a bulk extraction test averages away the problem. If someone asks, “How do you clean under a QFN/LGA?” they aren’t asking a beginner question. They are probing the core of whether the cleaning story is real or theater.

Practically, validation must be localized around the sensitive node. A guard ring around an electrometer input, a high‑value divider network, or an HV creepage region is not “just another area of the board.” It is a hotspot with different failure physics. The leakage path often follows mundane features: solder mask edges, via‑in‑pad neighborhoods, or the perimeter of a low‑standoff package where flux residues get trapped and activated by moisture. This is why “just increase spacing” rarely solves HV reliability on an assembly that still has residues: surface films do not respect the nominal spacing drawn in CAD.

Shiny is not a measurement.

The uncomfortable truth is that many programs validate cleaning as if contamination were uniform and visible. High‑impedance and HV failures are usually neither.

The Mechanism Trace: Residue → Moisture → Bias → Leakage (and How to Prove It)

A validation plan starts by stating the failure mechanism in one sentence. For this topic, it is usually surface conduction and drift (sometimes progressing toward electrochemical migration), not immediate breakdown. Then the plan lists the necessary conditions: ionic residue somewhere on the surface or trapped under a package, humidity high enough to create a conductive film, an applied electric field across the region (bias), and enough time for the leakage to stabilize into “new normal” behavior. That time component is what teams underestimate; lab tests are short, while field exposure is long.

Once that causal chain is named, the plan maps where each ingredient hides on the assembly. Under a low‑standoff LGA/QFN near a 100 MΩ divider is a classic trap: the region is electrically sensitive, physically hard to wash, and easy to contaminate during rework. When a program sees drift clustering after coastal deployment or summer warehouse storage, it rarely means the board became “dirtier” in a dramatic way. It means the environment finally supplied the moisture needed to complete the circuit across a residue film that was already there, and bias made the leakage path consistent.

A biased humidity soak is not a fancy test in this context; it is a way to reproduce the actual ingredients of the field failure. And it has a falsification standard: if biased humidity at a relevant stress level does not change insulation resistance over time in the hotspot region, the residue hypothesis loses strength.

This is also where the “ROSE pass = safe?” confusion should be handled. Bulk ionic tests can be useful screens, but they do not guarantee that the one square centimeter under a low‑standoff package near a guard ring is clean. They also rarely mimic operating conditions—the extraction chemistry, location sampling, and sensitivity to localized residues matter. A report can be “true” and still irrelevant to the failure mechanism. The validation question isn’t “Did it meet a number?” It’s “Does this assembly maintain insulation behavior under humidity and bias for the time constants the product will actually see?”

There is no universal “acceptable residue” threshold that can be asserted honestly for all high‑impedance/HV designs. The acceptable level depends on impedance scale (nanoamps are not microamps), voltage gradients, geometry, and environment. The way to manage that uncertainty is correlation, not confidence. Pick a representative board or coupon strategy, apply a biased humidity profile that brackets plausible field conditions (85°C/85%RH is a common bracket, but not the only one), and correlate localized contamination indicators (localized extraction around the hotspot, SIR/ECM style tests, insulation resistance vs. time) to the electrical performance you care about.

The throughline is simple: if the failure involves humidity + bias + time, the validation has to involve humidity + bias + time, in the right place.

Minimum Viable Validation Package (What It Proves, What It Doesn’t)

A “minimum viable validation package” isn’t a watered‑down version of a perfect program. It is a deliberate compromise: enough to rule out the most common false confidence loops without turning the project into an open‑ended science effort. It stops treating a certificate as a finish line. Rather than adding testing for its own sake, this package represents the smallest set of controls and proofs that meaningfully reduces the probability of drift/leakage returns.

At minimum, the program needs two categories: (1) screening/process evidence that cleaning is controlled and repeatable, and (2) at least one mechanism‑linked electrical proof test focused on the hotspot.

On the process side, the program should demand auditable artifacts from the cleaning line and the CM, not marketing statements. Consistently stable programs have specific traits: a documented wash recipe, maintenance records that include nozzle inspection/cleaning on an aqueous in‑line washer with spray bars, and a loading method that avoids shadowing (basket spacing rules that are actually followed, not just taped to a door).

Rinse quality deserves disproportionate attention because it is easy to neglect and changes outcomes. DI rinse resistivity logging that trends over time is more informative than arguing about a “stronger” chemistry while rinse water quality floats. This is also where material compatibility belongs—connector housings, labels, silicones/underfills, gaskets. A chemistry swap that hazes plastics or swells a gasket can “solve” contamination only to create a different reliability problem. A basic coupon check plus datasheet/SDS review is mandatory when substitutions are in play.

On the mechanism side, pick one test that resembles the failure ingredients and one measurement that targets the hotspot. That might be a biased humidity soak with defined bias across the sensitive region (HV spacing or the high‑value divider area) combined with insulation resistance vs. time trending, or SIR/ECM testing oriented around the process and materials used. Pair it with localized extraction around the high‑risk region (guard ring neighborhood, under low‑standoff packages) rather than a whole‑board average. The point is to make the program sensitive to the way these failures actually occur: localized, activated by humidity, stabilized by bias, and revealed over time.

Procurement and early troubleshooting often lead with a mis‑question: “Which cleaner should we buy?” If cleaning results change when boards are rearranged in a basket or when spray nozzles are unclogged, the team does not have a chemistry problem. It has a process capability problem. Chemistry selection matters—especially with flux types and materials constraints—but it is the last knob to turn after mechanics, loading, rinse quality, and monitoring are visible and controlled.

And no: conformal coating is not a cleaning plan. Coating can reduce risk, or it can seal residues into the assembly and turn them into long‑term drift sources. If coating is used, it needs its own process controls (masking strategy, thickness measurements logged per lot, cure verification, and a rework plan) and it still cannot be treated as permission to skip hotspot cleanliness validation.

Rework and Selective Solder: Validation’s Blind Spot

If a validation plan ignores rework, it validates a fictional manufacturing process.

A pilot build can pass ICT and look stable, then develop intermittent high‑impedance failures after a day in a humidity chamber with bias applied. The post‑mortem often reveals something painfully ordinary: two technicians performing “the same” touch‑up used different fluxes and different cleaning habits. One used a flux pen and a cotton swab with IPA; another used a different flux and a wipe material that shed fibers. A work instruction saying “clean as needed” is just a wish. When failures get tied back to MRB notes or NCRs and then to the rework bench, the pattern stops looking random. It starts looking like an uncontrolled second manufacturing process.

This is why rework and selective solder must be in the validation scope. The controls are explicit: a locked flux list (part numbers tracked in the tool crib), defined solvent and wipe materials (no “folk recipes” dependent on the person), clear routing rules for when boards must go back through wash after touch‑up, and verification criteria that match the failure mechanism (not just “looks clean”). If a program has to live through ECOs and field service repairs, the validation should include at least one rework cycle in the test matrix for the hotspot region, because that is where residues get injected late and silently.

There is also a subtle but important uncertainty to manage here: “no‑clean” on a flux label is not a physics guarantee, and formulations vary. Treat flux type as a controlled variable. When it changes, re‑validate the hotspot behavior under humidity and bias. Otherwise, the program ends up “validated” for a flux that isn’t the one being used during the messy, time‑pressured touch‑ups that actually happen.

Rework volume can be small and still dominate risk because the sensitive node is localized. The risk is proportional to whether a rework event touched the wrong square centimeter, not how many boards were reworked total.

Red‑Teaming the Comfort Artifacts (ROSE, CoCs, Visual, Hipot)

The mainstream mindset is simple: hit the cleanliness KPI, pass hipot, ship. The comfort artifacts are stacked like a shield: ROSE report, supplier CoC, visual inspection, maybe UV tracer dye, and a hipot pass at the end. Each artifact measures something real, but none of them, by itself, measures “this assembly will not develop surface conduction and drift at humidity under bias over time.”

ROSE is a coarse bulk screen; it is not designed to map localized residues under a QFN perimeter or at a guard ring edge. A supplier CoC describes incoming material, not the state of the assembled board after reflow, selective solder, handling, and rework. Visual inspection (even with UV aids) helps catch gross residue and workmanship issues, but thin electrically active films can be nearly invisible. Hipot proves a moment‑in‑time withstand under a specific setup; it does not automatically predict surface conduction drift at 85%RH with bias applied for hours or days. These aren’t criticisms of the tests. They are reminders of their limits.

If the product cares about nanoamps, it should validate with nanoamps—or with tests that reliably predict them.

A pragmatic rebuild keeps the comfort artifacts as screens, but stops using them as closure. Add one mechanism‑linked proof test at the hotspot under humidity and bias for a relevant time, and pair it with localized contamination measurement or SIR/ECM‑style evidence. That single addition often does more to prevent drift‑driven field returns than expanding a checklist of certificates.

How to Scope It Without Starting a Science Project

A credible program does not try to validate “cleanliness” everywhere, forever. It scopes around consequence and plausibility.

Start with the sensitive node and its neighborhood: high‑value dividers (100 MΩ and up), electrometer inputs with guard rings, and HV spacing where surface films can bridge creepage. Then decide what the product’s world looks like in ranges: benign indoor, coastal humidity exposure, or hot warehouse storage followed by moisture during shipping and deployment. That scoping decision informs test stress selection. It also informs sampling: localized extraction around the hotspot is more informative than whole‑board averages when under‑component entrapment is the failure driver. If the CM can show rinse resistivity trends, washer maintenance logs, and loading diagrams that prevent spray shadowing, that reduces the need for repeated exploratory testing. If they cannot, the program should assume variability until proven otherwise.

This guide intentionally avoids ranking cleaner brands, providing hobbyist cleaning steps, or walking through a standards clause‑by‑clause history. That material does not help a pro team decide whether a high‑impedance/HV assembly will remain stable under humidity and bias. It tends to distract from the levers that actually matter: geometry, process capability, and mechanism‑linked validation.

The practical north star is straightforward: stop asking whether the board is “clean” in the abstract. Ask whether the hotspot stays insulating across humidity, bias, time, and rework reality—and require measurements that can answer that question.