A unit can leave the line with green functional test logs and still show up “dead on arrival.” That phrase has a way of dragging a team straight into firmware screenshots and power-rail debates.

It’s usually a trap. Post-ship and post-install failures often come from motion, strain, and looseness—mechanical mechanisms that mimic electrical faults. If the first instinct is “the carrier dropped it,” the better move is to open a unit and look for witness marks, loose hardware, and connector retention issues before anyone starts rewriting code.

This is about the unglamorous middle: harness routing that doesn’t depend on operator interpretation, fasteners that use a verification system instead of a torque note, and pack-out that assumes carriers do not care.

The Trap: It Passed Test, Then Died

When a device passes ICT/FCT and starts resetting only after installation, the narrative becomes predictable: brownout, EMI, firmware timing. In late 2021, a gateway pilot run of about 1,200 units had under 1% electrical failures at functional test, but early RMAs climbed to roughly 4.6% within the first couple of months. The test rack exports were boring in the best way. The field returns were not.

The mechanism wasn’t mysterious once someone stopped staring at logs and opened the box. A returned unit showed a harness routed under a stamped bracket; the insulation had a shiny, polished wear spot where it had rubbed. On the line, operators were doing what the system rewarded—routing whatever way made the lid close fastest—because the work instruction said something like “dress harness to avoid pinch” and did not constrain the route with photos or tie points. That’s how one lot becomes three build variants, and only one of them survives vibration exposure (in this case, an install environment like Houston, where equipment sees real vibration and handling).

The point isn’t just “watch for chafe.” These problems sit in three buckets that can be controlled: harness routing/strain relief, fasteners/grounding discipline, and pack-out that prevents the product from hurting itself in transit.

Mechanism Trace: The Fast Walkback (Symptom → Evidence → Control)

A useful habit in box build integration is a short walkback from the symptom to physical mechanisms and then to evidence. “Intermittent after shipping” and “only after install” are timelines, not root causes. Timelines narrow what mechanisms are plausible: connector back-out, harness strain at a panel cutout, loose grounds that shift under vibration, fasteners “torqued” by an out-of-calibration clutch tool, or internal motion from packaging that lets a cable bundle slam into an edge.

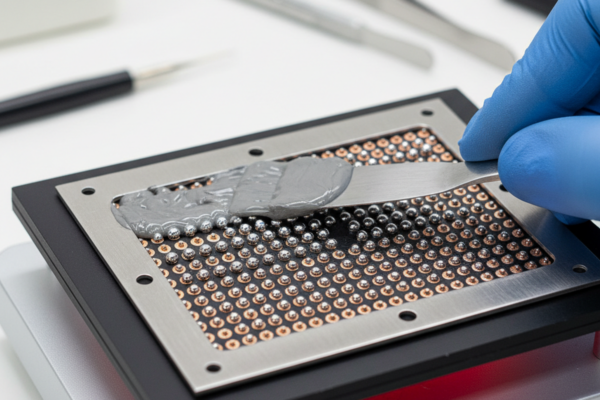

That habit keeps the investigation honest. If the hypothesis is “EMI,” there should be evidence that survives handling and teardown. In one 2018 incident tied to Ontario field returns and a looming compliance retest, the plots looked noisy and people reached for ferrites. The faster check was mechanical: a ground lug screw inside an RMA unit could be turned with fingertip pressure. The torque spec existed, but the driver was a worn clutch tool overdue for calibration, and access to that lug was awkward after the harness went in. Changing the build sequence so the lug was torqued before the harness blocked access, adding paint witness marks, and fixing the powder-coat masking under the ring terminal cleaned up the symptoms without a schematic change.

This is where “passed test but arrived dead” needs a reset. Shipping adds energy: drops, corner crush, vibration. If a unit can move inside a carton, it will, and the impacts won’t be evenly distributed. In a carrier damage audit, 18 of 30 returned cartons showed corner crush; inside, the units had repeatable witness marks where a bundle had been pressed against a heatsink edge. That’s not random bad luck. It’s a mechanism with an evidence trail.

If nobody can point to physical evidence—witness marks, fastener witness paint, foam abrasion, connector latch condition—then nobody has a root cause yet.

Harness Routing: Stop Rolling Dice

Harness routing is not a shop-floor improvisation. It’s a design feature. Either it exists—meaning it is constrained and auditable—or it doesn’t, and production becomes a routing lottery.

The 2021 bracket-edge chafe story is a clean example because it shows how variability enters. The work instruction language (“avoid pinch,” “tie as needed”) allows multiple interpretations. Operators will pick the one that minimizes hassle in that moment: quickest lid closure, easiest reach, least fighting the bundle. In one lot, three routings appeared because the system never defined a single “good” route. Only the “tight” routing rubbed a feature and failed after vibration. When someone later asks, “why can’t the line follow instructions,” what they often mean is “why can’t humans read our minds.”

The fix pattern is consistent: define a golden sample, then harden the work instruction so it’s hard to misread. That usually includes two to three specific retention points (a molded clip, a defined tie location, a strain relief near a panel cutout), plus a slack callout near the connector that prevents the harness from acting like a lever during vibration. In a 2019 corrective action, adding a single molded clip (HellermannTyton-style) and a roughly 15 mm slack callout cut intermittent disconnect RMAs by about 70% over the next quarter. Not because clips are magical, but because they remove interpretation.

A routing spec that survives scale tends to replace vague verbs with checkable outcomes. Examples that actually work in a CM or EMS environment:

- “Dress harness” becomes “route above bracket, not under; clip in Hole B; tie 10–15 mm from chassis boss.”

- “Avoid pinch” becomes “no harness between lid flange and chassis; verify 360° clearance at lid close.”

- “Secure as needed” becomes “use one tie only at Location C; tail trimmed; no ties on connector backshell.”

The discomfort here is social, not technical. This feels prescriptive because it is prescriptive. The alternative is variability, and variability is a failure mode.

There’s also an installer reality check that changes how strict this needs to be. On a 2023 site visit in Phoenix, an installer was balancing an enclosure on a ladder rung, wearing gloves, using a headlamp, in dust and heat. The “routing suggestion” page in a binder did not control what happened. The installer shoved the harness aside to close the lid and moved on. Two weeks later, the same unit came back with a pinched cable and a partially unseated connector. That isn’t a field operator problem. It is a design and integration control failure. If a step is important, it must be physically hard to do wrong.

Harness routing and fastener discipline share the same moral: intention doesn’t ship—verification ships.

Fasteners & Grounds: Torque Without Verification Is Theater

A torque value on a drawing is not a torque system. Torque control without verification is theater, and it fails quietly until shipping vibration and thermal cycling make it loud.

A torque system has five parts: a spec (tied to the actual fastener/material stack), a tool (and a calibration schedule), access and sequence (so the tool can be used correctly), a verification method (witness marks or audits that catch drift), and bounded rules for any locking method. In the 2018 ground lug incident, the biggest change wasn’t a new number—it was sequencing the ground lug before the harness blocked access, and adding witness marks so an auditor could see “torqued” versus “touched.”

This is where teams waste time. “Noisy pre-scan” becomes “we need better filtering.” “Random resets” becomes “firmware watchdog.” But loose grounds and under-torqued fasteners can create electrical-looking symptoms, especially when powder coat or paint sits under a ring terminal. The fastest verification is mechanical: torque audit on the critical lugs, check contact surface prep (star washer, masking spec), and check the tool calibration record. That path is usually hours, not weeks.

Thread-lock is where the temptation to “do something quick” creates new problems. Blanket instructions like “blue Loctite on everything” are exactly how a line does well-intentioned damage. In early 2020 during a Tijuana CM audit, a change request meant to stop loosening became “apply liquid thread-lock to all screws.” Plastic bosses started cracking during final assembly, and residue showed up where it didn’t belong, including near a micro-fit connector. The fix wasn’t banning thread-lock; it was bounding it: metal-to-metal fasteners that see vibration may use a defined method (often a pre-applied patch is cleaner), plastics are typically excluded, and “no liquid thread-lock near connectors” is a sane rule because contamination is real and rework is a reality.

Fastener mistake-proofing also gets ignored until a demo dies. In 2017, a prototype failed after being carried across a building because the wrong screw length was used: an M3 pan head in 10 mm instead of 6 mm, from two bins both labeled “M3 pan head.” The screw tip grazed a PCB keepout near an enclosure wall—barely visible, but enough for a latent short when the unit flexed. Kitting fasteners with separated compartments and a photo sheet, and forcing explicit callouts on the assembly drawing, is not glamorous. It is cheaper than a week lost to “PCB reliability” arguments.

Torque values are context-specific, and nobody should pretend otherwise. But the structure—spec, calibrated tool, access/sequence, verification, bounded locking rules—is not optional if the goal is to ship low-RMA product.

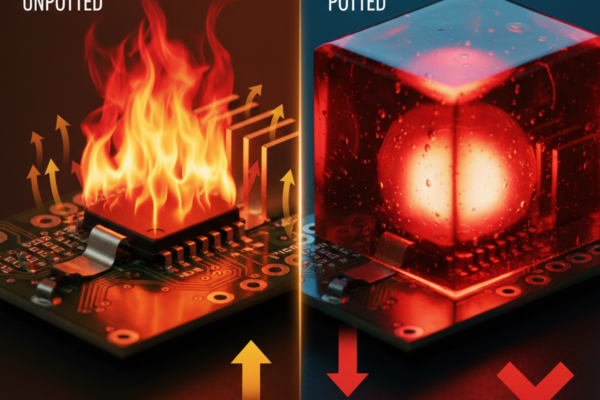

Pack-Out: Engineer for Carrier Indifference

Packaging is not a logistics afterthought. It is part of the mechanical system, and it has to be designed for carriers that do not care.

The core question is simple: what can move inside the carton, and where does the energy go when the carton is dropped or crushed? In 2019, damage photos had a repeatable pattern: the top-left corner of cartons took hits, and inside, the product could yaw and slam into the foam. The foam cradle fit a nominal unit, but tolerance stack plus a bulging cable bundle changed the real fit. The unit didn’t need a stronger sheet metal ear; it needed immobilization and corner protection so it stopped hurting itself.

“Fragile” stickers and orientation arrows are wishful thinking. Insurance claims are administrative hobbies, not controls. Carrier handling is weather. Packaging is engineering.

The practical controls are not mysterious. Immobilize the product so it cannot gain momentum. Protect edges where energy concentrates (corners, protruding ears). Account for tolerance stack and cable bundle bulge when you design the foam geometry. Treat “this side up” as optional unless it is enforceable in the real distribution channel; otherwise design for any orientation. And add one pack-out behavior that catches drift: a simple shake test at the dock—if you can feel movement, it’s wrong.

Packaging has trade-offs (cost, weight, sustainability), and the right test standard depends on distribution channel, unit weight, and warranty cost. The important boundary is honesty: don’t claim compliance to an ISTA level without a test report. A pragmatic minimum on-ramp is still possible: do a basic face/edge/corner drop sequence on a packed unit, add a vibration exposure appropriate to your channel, and include a stack/compression check if palletization or warehousing is involved. The goal isn’t to pass a paper standard; it’s to catch the harness clip that pops loose before customers do.

Red-Team the Comfort Stories, Then Do the Minimum That Works

The comfort stories are familiar: “It’s the PCB,” “It’s the operators,” “It’s the carrier.” Those stories feel good because they let teams stay in their own lanes. They also waste time. The faster model is: if a failure shows up after shipping or install, assume mechanical mechanisms until evidence says otherwise—then install auditable controls that make the correct build hard to drift away from.

If there’s only time for a 60-second check on an “arrived dead” unit before a meeting derails:

- Look for witness marks on harness insulation near edges, brackets, and heatsinks; shiny rub spots are a clue.

- Check critical fasteners and grounds for verification (paint witness marks, torque audit marks, contact surface prep around the lug).

- Check connector retention and strain relief (latch engaged, secondary lock if used, no harness acting as a lever at a panel cutout).

A few common questions come up in these programs. “Should they just train the line better?” Training helps, but it’s an unreliable control when the WI says “tie as needed” and the design allows three routings. “Should they add thread-lock?” Sometimes, but only with bounded rules and material awareness; otherwise it creates cracked plastics and contamination. “Should they just use better packaging?” Yes—but “better” means motion control and tolerance-stack reality, not thicker cardboard and more stickers.

If the goal is max-min risk reduction—largest cut in warranty and field pain per unit effort—three moves dominate: constrain harness routing with a golden sample and auditable WI, implement a torque system with verification (and sequence/access that make it possible), and design pack-out to immobilize the product under carrier-indifference assumptions.