The failure usually lands in the RMA pile disguised as a “software glitch.” A USB security key stops authenticating after a few weeks. A PCIe card in a server rack drops off the bus intermittently, triggering a kernel panic. The software team spends weeks debugging drivers, but the root cause isn’t code. It’s visible only under 20x magnification.

If you zoom in on the edge connector of those failed boards, the story is violent. The gold plating hasn’t just worn down; it has been sheared off entirely. What remains is a smear of black nickel oxide and exposed copper. The contact resistance has spiked from a manageable 30 milliohms to an open circuit.

This isn’t a manufacturing defect in the traditional sense. The board was built exactly to print. The failure happened in the design software, the moment a simplified “Gold Plating” specification was applied to a connector meant to survive the physical brutality of insertion.

Physics vs. Marketing Brochures

There is a pervasive misconception in procurement and junior engineering circles that “gold is gold.” If the datasheet says the finish is gold and it conducts electricity, the assumption is that it works for a connector. This belief is expensive because it ignores the fundamental material science of the metal. Pure gold is incredibly soft. In the world of metallurgy, we measure this softness on the Vickers Hardness (HV) scale.

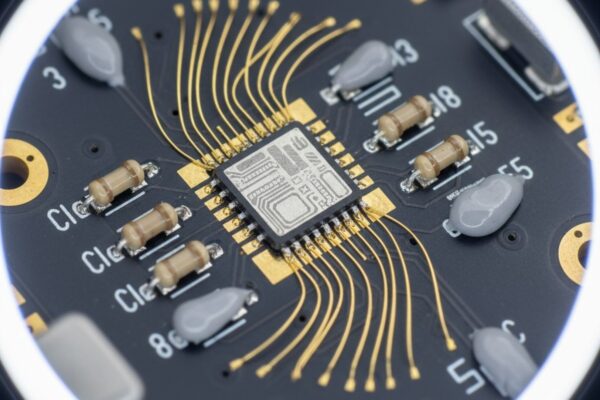

Electroless Nickel Immersion Gold (ENIG), the standard finish for most modern surface-mount boards, is almost pure gold. It typically clocks in between 60 and 90 HV. It is soft enough that a fingernail can leave a mark on it. When you slide an ENIG-plated board into a mating connector, the metal springs inside that connector act like hardened steel plows digging into the soft gold surface. Within 10 to 20 insertion cycles, the gold is gone. You have ground through the finish and are now mating the connector pins directly against the underlying nickel. Nickel oxidizes rapidly when exposed to air, creating that black, resistive layer that kills the signal.

To withstand the shear forces of insertion, you cannot use pure gold. You need “Hard Gold,” technically known as Electrolytic Nickel Gold. This is an alloy, usually doped with small amounts of Cobalt or sometimes Nickel, which fundamentally alters the crystal structure of the deposit. Hard Gold registers between 130 and 200 HV on the Vickers scale. It doesn’t plow; it glides. It is designed to survive hundreds, sometimes thousands, of mating cycles without exposing the base metal.

We often see vendors or fab houses suggesting “Thick ENIG” as a middle ground—simply leaving the board in the immersion bath longer to build up a thicker layer of pure gold. This is a trap. While it might delay the wear-through by a few cycles, it introduces a new risk: “Black Pad,” a brittle fracture phenomenon caused by corrosion of the nickel layer during the extended immersion process. Furthermore, you are still fighting physics with the wrong material. A thicker layer of soft butter is still butter; it won’t resist the knife.

The Manufacturing Constraint: Tie Bars

If Hard Gold is the superior choice for connectors, why isn’t it the default for the entire board? The answer lies in the manufacturing process. ENIG is a chemical process; you dip the board in a tank, and the reaction happens everywhere copper is exposed. It is elegant, flat, and requires no external connections.

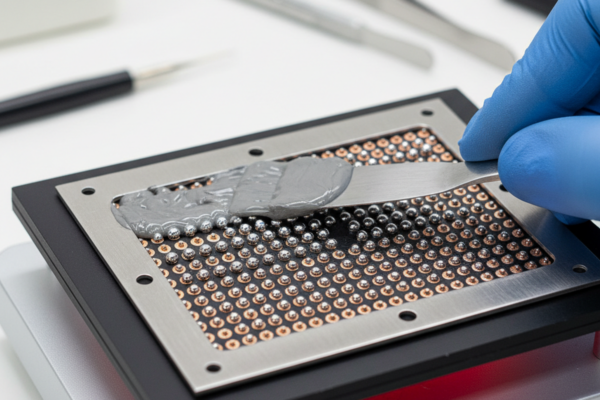

Hard Gold is electrolytic. It requires an active electrical current to drive the gold ions onto the surface. To get that current to the edge connector fingers during fabrication, the board designer must include “tie bars” or “bus lines”—traces that physically connect the gold fingers to the edge of the production panel. These traces carry the current during the plating bath.

After the plating is done, the board is routed out of the panel, and those tie bars are severed. You can often see the remnants of them if you look closely at the very tip of a gold finger—a small spot of exposed copper where the connection was sliced. This requirement imposes constraints on the layout. You cannot easily have “floating” hard gold islands in the middle of a board. It also means the process is additive in terms of labor and steps. The fab house has to run a separate masking process to cover the rest of the board, plate the fingers, and then finish the rest.

This leads to a common friction point in quoting. A procurement manager sees the line item for “Hard Gold Fingers” adding 5-10% to the board cost and asks, “Can’t we just use the same finish as the rest of the board?” Or conversely, they ask to plate the entire board in Hard Gold to simplify the process. This is equally dangerous. The Cobalt that makes Hard Gold durable makes it terrible for soldering. Solder joints on Hard Gold are brittle and prone to failure. The rule is rigid: ENIG (or OSP/Immersion Silver) for the components, Hard Gold for the connector. Never mix them.

The Calculus of the Recall

The decision to skip Hard Gold is almost always financial. On a prototype run of 50 boards, the setup fee for hard gold might add $200. On a production run of 10,000 units, it might add $0.40 per board. In the spreadsheet, saving $4,000 looks like a win.

But reliability is an economic metric as much as an engineering one. We have to weigh that $0.40 against the cost of the failure. If the device is a disposable sensor that is plugged in once during assembly and never touched again, ENIG is technically acceptable. The “insertion count” is one. The risk is low.

But if the device is a USB dongle, a memory card, or a modular daughterboard, the user will plug it in. They will unplug it. They will toss it in a bag and plug it in again. If that connector fails after six months, the cost is not $0.40. The cost is the shipping of the return, the labor of the failure analysis, the replacement unit, and the reputational damage.

We analyzed a case involving a custom RAID controller where the vendor saved roughly $1.20 per board by using ENIG on a PCIe edge connector. The connectors began to oxidize in the field, increasing resistance. The heat generated by that resistance didn’t just fail the card; it melted the plastic PCIe slots on the host motherboards. The “savings” on plating resulted in a requirement to replace 200 server motherboards manually. The ROI on that decision was catastrophic.

The Geometry of Insertion

Even with the correct metallurgy, the physical shape of the board edge can destroy a connector. A standard PCB is routed with a milling bit, leaving a 90-degree sharp edge. If you force a 1.6mm thick board with a sharp 90-degree edge into a connector, you are essentially using a guillotine on the connector pins.

This is where the “Chamfer” or “Bevel” specification becomes critical. A proper edge connector requires the PCB edge to be angled, typically to 20 or 30 degrees. This ramp allows the connector pins to ride up onto the gold pads smoothly rather than colliding with the leading edge of the fiberglass.

It is common to see designs that specify “Hard Gold, 30 micro-inches” but forget to specify the chamfer. The result is a board that is chemically perfect but mechanically destructive. The connector pins catch on the fiberglass, bend, or scrape violently against the leading edge of the gold, pre-wearing the surface before the device is even fully seated. If your fab house doesn’t ask you about the bevel angle when you submit a design with edge fingers, they are letting you walk into a trap.

The Final Specification

When you sign off on a BOM, you aren’t just buying parts; you’re buying probability. To ensure the probability of connection failure remains near zero, the specification on the fabrication drawing must be explicit. Do not rely on the vendor’s default.

- Specify the Material: Explicitly request “Hard Electrolytic Gold” or “Gold/Cobalt Alloy.”

- Specify the Thickness: “Flash gold” is a marketing term, not a spec. For standard edge connectors (PCIe, USB, ISA), the industry standard (IPC-6012 Class 2/3) typically demands a minimum of 30 micro-inches (approx 0.76 microns). Anything less than 15 micro-inches is effectively a wear-out timer.

- Specify the Geometry: Call out a 20-30 degree chamfer on the mating edge.

There is no software patch for a worn-out contact. Once the gold is gone, the device is dead. The extra cents spent on the correct plating are the cheapest insurance policy you will ever buy.