The worst nightmare in electronics manufacturing isn’t the board that fails on the line. Line failures are annoying, sure—they stop the conveyor, summon the tech, and eat into the shift’s yield metrics. But the real nightmare is the “Ghost Board.”

This is the unit that fails in the field, perhaps three years later, inside an automotive sensor or a medical device. It comes back to the RMA bench covered in road grime or biological residue. You flip it over to scan the serial number, to trace the batch, to find out which capacitor lot caused the failure, and you find… nothing. A smear. A beige rectangle where a barcode used to be.

The ink has flaked off, dissolved by the conformal coating, or simply surrendered to time. At that moment, you don’t just have one bad board; you have a potential recall of unknown magnitude because the audit trail washed away with the serial number.

Traceability isn’t a suggestion; it is the backbone of modern liability. Yet, many production lines still rely on methods that treat the serial number like a temporary sticker rather than a permanent feature of the hardware. If you are still printing serial numbers with wet ink or applying them with adhesive labels, you are building a failure point directly into the product’s identity. The only mark that survives the hostile environment of an SMT line and the long decay of the field is the one that removes material rather than adding it: laser ablation.

The Chemistry of Failure: Why Ink Surrenders

To understand why ink fails, look at what you are subjecting the PCB to. The standard SMT process is a gauntlet of thermal and chemical violence. You print a serial number on a bare board, often using a UV-cured epoxy ink. It looks crisp under the inspection lamp.

But then that board enters the wash. Modern flux residues require aggressive saponifiers—alkaline chemicals designed specifically to break down organic compounds. Ink is an organic compound. Over hundreds of cycles, or even just a few aggressive washes with high pressure and high temperature, the bond between the ink and the solder mask weakens. It micro-cracks. It lifts.

It isn’t just about the wash, either. Consider the chemical interaction with subsequent layers. If you apply a conformal coating—say, a Type UR (Urethane) or SR (Silicone)—that coating uses solvents to stay liquid before curing. Those solvents can react with the ink of the silk screen. I have seen “permanent” white markings turn into a brown sludge under a layer of urethane, rendering the barcode unreadable to anything but the human eye—and even then, only with a lot of guessing. A barcode scanner does not guess. If the contrast drops below a certain threshold, the line stops. Or worse, the data is lost.

There is often a temptation to bypass the mess of ink by using labels. “High-temperature” polyimide stickers seem like the clean solution. They aren’t. They are foreign object debris (FOD) waiting to happen.

A sticker relies on adhesive, and adhesive is a polymer that softens when heated. When that board hits the pre-heat zone of a reflow oven, ramping up to 150°C, the adhesive gives way. If you have high-velocity convection fans blowing air to circulate heat, those labels can lift. They fly off the board and get sucked into the intake of the oven’s blowers. Now you have a board with no identity, and you have a $50,000 Vitronics Soltec oven that needs to be dismantled to scrape melted plastic off the impellers.

Machine Vision and the Physics of Contrast

The goal of a barcode isn’t to be seen; it’s to be read by a machine. A Keyence or Cognex fixed-mount reader does not care about aesthetics. It cares about contrast—specifically, the difference in reflectivity between the “cell” (the dark part) and the background.

Silk screen ink sits on top of the solder mask. It has thickness and sheen. Under the coaxial lighting of a scanner, wet ink can glint, creating specular reflections that blind the sensor. The edges of a silk-screened dot are also imperfect; the ink slumps and spreads (dot gain), making a 10-mil cell look like a 12-mil blob.

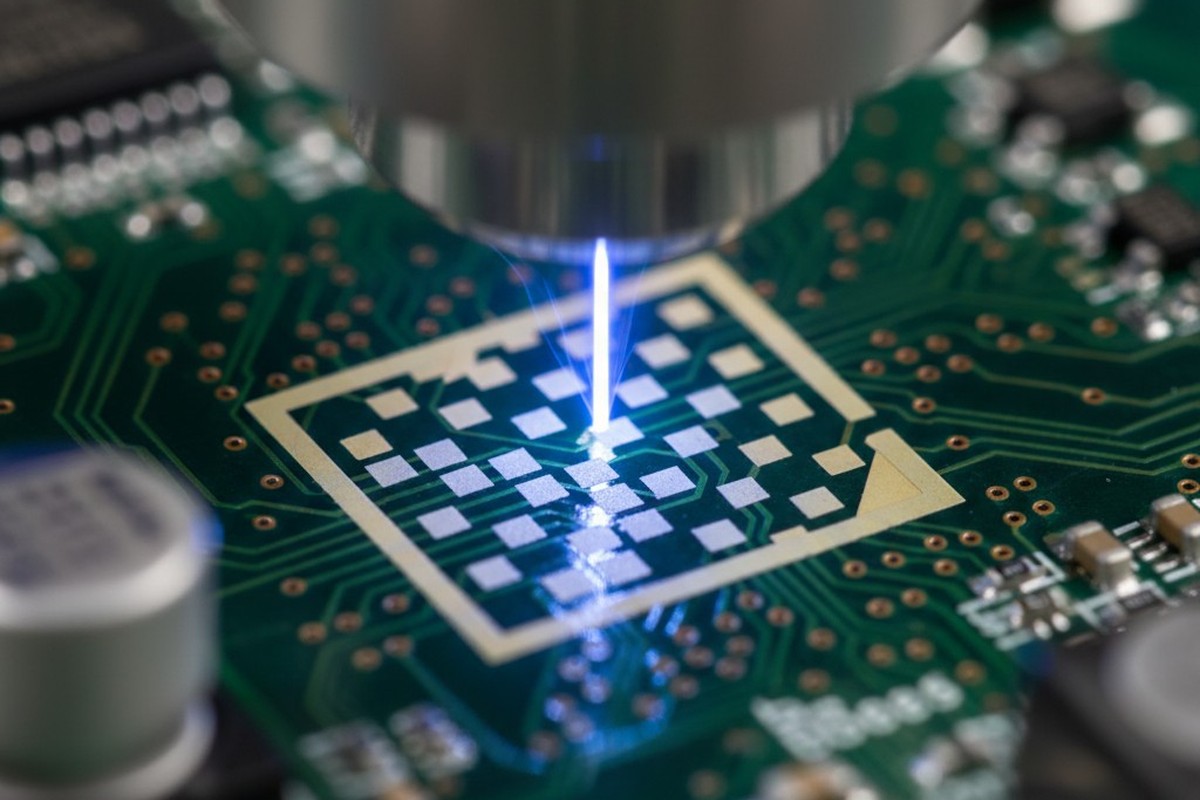

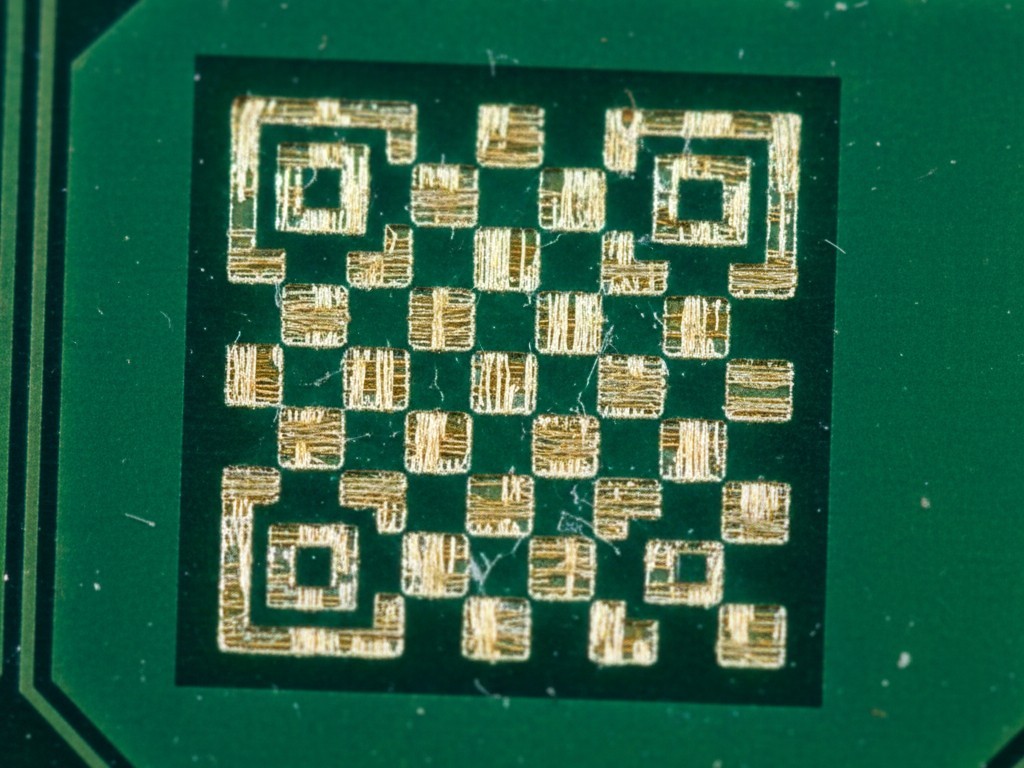

Laser marking works on a fundamentally different principle. It is subtractive. You aren’t adding white ink to a green board; you are using a CO2 or Fiber laser to burn the green solder mask away. This ablation exposes the material underneath. If you tune the laser correctly, you expose the FR4 fiberglass substrate, which is typically a pale yellow-white.

This creates a recess—a physical trench. The dark green mask surrounds the light FR4. The contrast is stark, matte, and permanent. It does not glint because the mark is below the surface of the mask. The edges are cut with the precision of a photon beam, not the squish of a squeegee.

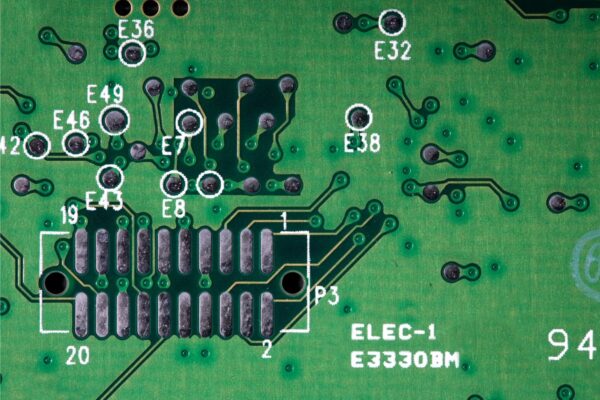

Let’s clear up a confusion that appears on almost every CAD drawing: You probably don’t want a “QR Code.” A QR code is that massive blocky thing you scan to see a restaurant menu. It is designed for consumer marketing. On a PCB, where real estate is worth dollars per square millimeter, you use a Data Matrix (specifically ECC 200). A Data Matrix can store 50 characters of alphanumeric data in a 3mm x 3mm square. It has redundancy built in. Don’t ask for a QR code; ask for a Data Matrix. The laser handles them natively, and unlike a QR code, a Data Matrix remains readable even if 20% of the symbol is damaged.

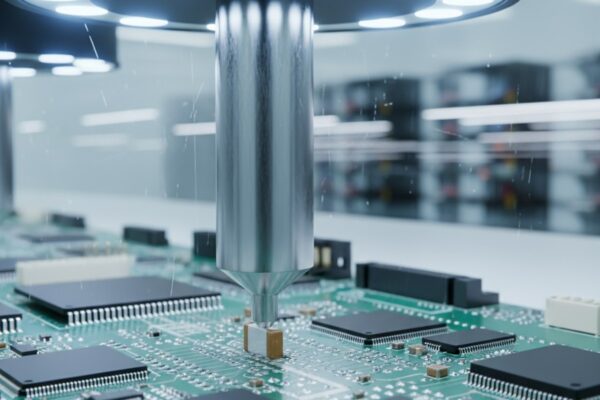

Integration: The Mark Must Precede the Process

The timing of the mark is as critical as the method. Some factories treat marking as a final packaging step—slapping a label on the finished unit before it goes into the box. This is a mistake.

Traceability is needed during the assembly process. You need to know that this specific board failed at the Automated Optical Inspection (AOI) station. You need to know that this board spent 45 seconds too long in the reflow oven.

To get that data, the mark must be applied to the bare board before it enters the screen printer. The laser marker should be the first machine in the line, or the board should arrive pre-marked from the fab house. However, marking in-house gives you control. You can serialize sequentially based on the exact time of assembly. By ablating the mark into the solder mask before the first drop of solder paste is applied, you ensure the mark travels with the board through the paste printer, the pick-and-place, the reflow oven, and the wash.

If the mark survives the process, it validates the process. If you mark at the end, you have zero granularity on your yield losses. You just have a bone-pile of scrap boards with no history.

The Total Cost of Ownership: Ink is Expensive Dirt

The resistance to laser marking is almost always the initial price tag. A decent inline fiber laser system is a significant capital expenditure (CapEx), often ranging from $20,000 to $60,000 depending on the automation. A silk screen station is cheap. A label feeder is cheap. But this is “spreadsheet math” that ignores the reality of the factory floor.

Calculate the cost of ink. Not just the tub of epoxy, but the screens. Screens stretch. They clog. They need to be washed with harsh solvents that require hazardous waste disposal. They have a shelf life. They require labor to mix the ink, setup the machine, and clean up the mess afterwards. Ink is a variable process; humidity affects cure time, viscosity changes with temperature.

The laser consumes electricity. That’s it. There are no consumables. No screens to wash, no hazardous solvent disposal fees, no shelf-life management. Once the focal height and power are dialed in, the laser does not drift. It does not clog. It runs for 50,000 hours before the diode pump needs attention. Over a three-year horizon, the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) of a laser is frequently lower than ink, even with the higher upfront cost.

There is one area where ink wins: massive fill areas. If you need a giant, solid-white company logo that spans three inches, a laser is slow. It has to hatch-fill that entire area line by line. A screen printer does it in one swipe. But we are talking about traceability here, not graphic design. If you need a pretty logo, screen it. If you need data that must survive a nuclear winter (or a 260°C oven), lase it.

The Sleep of the Just

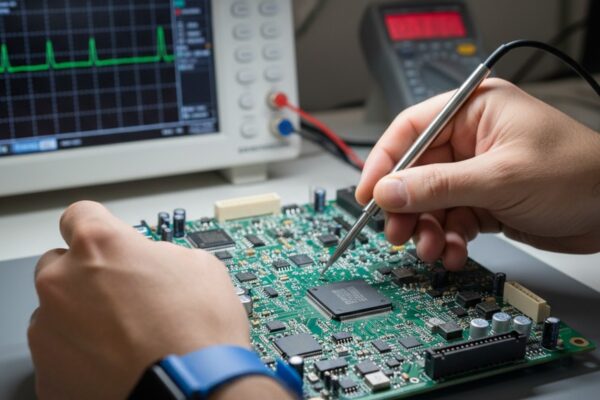

We don’t talk enough about the emotional toll of bad processes. The anxiety of the “2 AM phone call” is real. When a line goes down because a barcode reader can’t trigger, or when a customer audits your facility and finds illegible date codes, the cost is reputation.

There is a specific peace of mind that comes from picking up a scrap board that has been through hell—reflowed twice, washed in aggressive chemistry, scrubbed with a wire brush during rework—and seeing that the Data Matrix is still crisp, white, and scannable. It’s a permanent record of the work. It means that whatever happens to that board in the field, ten years from now, you will know exactly when it was made, who made it, and what parts are on it.

That is what you are buying with laser ablation. You aren’t just buying a machine. You are buying the certainty that your data is etched in stone, or at least, in FR4.