The most dangerous package on a receiving dock isn’t the one that’s obviously damaged. It’s the one that looks perfect. A standard Moisture Barrier Bag (MBB) arrives vacuum-sealed tight as a drum, the label is crisp, and the date code looks recent. To the untrained eye—or a hurried purchasing agent—this component is “dry.” But the physics of water vapor transmission often tells a different story.

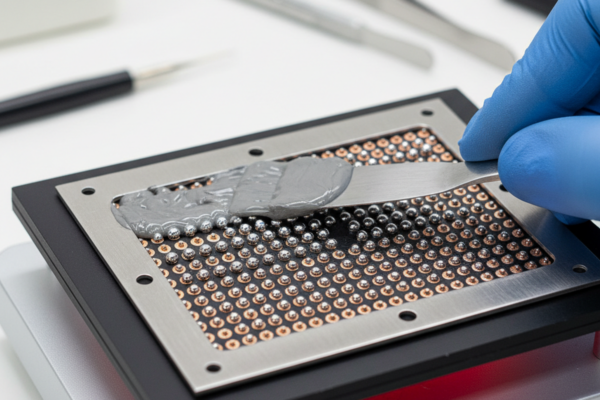

Vacuum pressure is a mechanical state, not a moisture barrier. A bag can be pulled to a perfect vacuum and still have a Moisture Vapor Transmission Rate (MVTR) that allows humidity to permeate the plastic over months of storage. When that water gets inside, it doesn’t sit on the surface; it adsorbs into the hygroscopic plastic encapsulant of the component itself. During the reflow process, when temperatures hit 240°C or higher, that trapped microscopic water turns to superheated steam instantly, expanding to roughly 1,600 times its original liquid volume.

The result is “popcorning”—internal delamination that tears wire bonds or cracks the die. You often won’t see this from the outside. Sometimes the part will even pass electrical testing today, only to fail in the field three months later. The tightness of the bag is an illusion; the only thing that matters is the chemistry inside.

The Humidity Indicator Card: The Only Witness

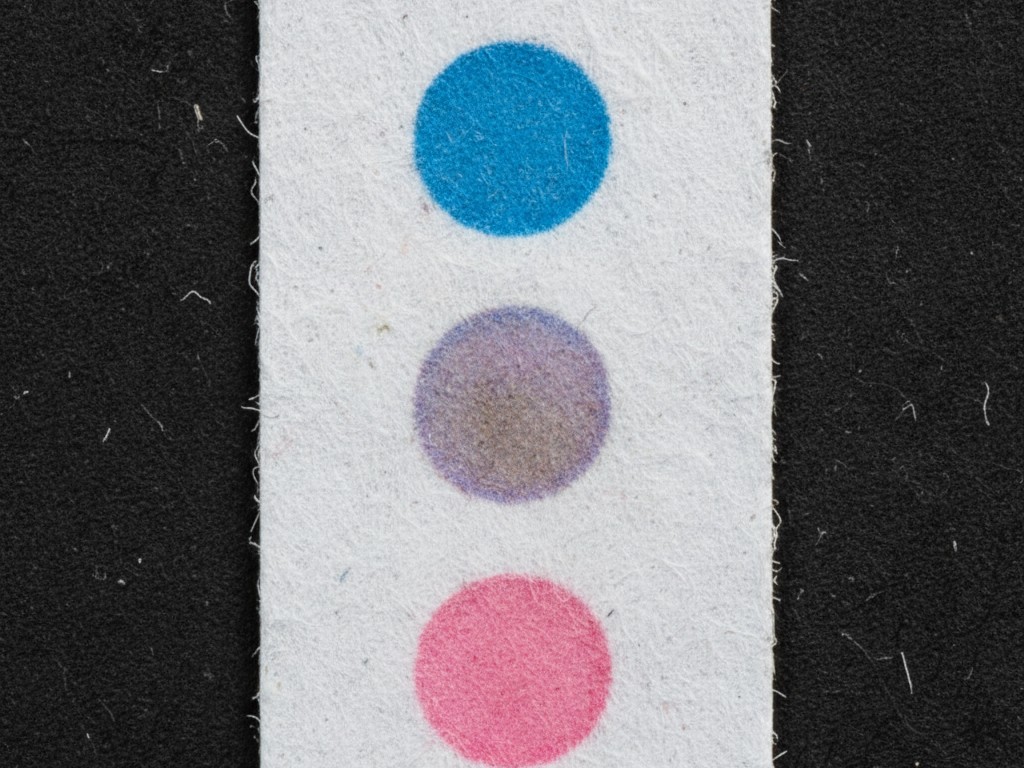

Once you cut that seal, you have exactly one reliable data point: the Humidity Indicator Card (HIC). This small piece of paper, impregnated with Cobalt Dichloride or similar humidity-sensitive chemicals, is the only witness to the environment the component has endured since sealing.

Paperwork and Certificates of Conformance (CoC) can be forged or simply disconnected from reality. A broker in Shenzhen can repackage a reel of MSL 3 microcontrollers that sat on a shelf for two years, vacuum seal them in a new bag with a new desiccant pack, and slap a “New” label on the box. But they often forget to bake the parts first, or they use a cheap HIC that reacts too slowly.

When you open that bag, look immediately at the HIC. Do not wait. The ambient humidity of your facility will begin to turn the spots pink within minutes, destroying your evidence.

J-STD-033D is explicit, yet this is where most errors happen on the shop floor. You are looking at the 10% spot (for standard work) or the 60% spot (for legacy checks), but there is a dangerous grey area here. The spot is supposed to be blue for dry and pink for wet. In reality, you will often see “lavender.” It’s a muddy, ambiguous purple that suggests the desiccant is working hard but failing.

If you see lavender on the 10% spot, assume the parts are wet. Do not let production pressure convince you that “it’s close enough to blue.” If the color has shifted even slightly away from the reference hue, the component has absorbed moisture. The desiccant is saturated. The safety margin is gone.

Be especially wary if you are dealing with independent distributors or brokers. A common trap occurs when a broker takes parts exposed to unknown humidity, seals them up, and ships them immediately. If the transit time is short (2-3 days), the HIC might not have had time to fully equalize and turn pink, even if the parts are wet. If the bag seal date is yesterday, but the parts are from 2019, the HIC is telling you the condition of the air in the bag, not the moisture in the part. In these cases, even a blue HIC is suspect.

The Oxidation Trade-Off: To Bake or Not to Bake?

When you identify a wet part, whether via a pink HIC or a broken seal, the knee-jerk reaction is to “just bake it.” Most production managers love the 125°C bake. It’s fast. According to the J-STD-033D lookup tables, you can often dry out a standard thickness package in 24 to 48 hours at this temperature. It fits the weekend gap: put the reels in on Friday, and by Monday morning, they are ready to mount.

But this speed comes with a severe hidden cost: oxidation.

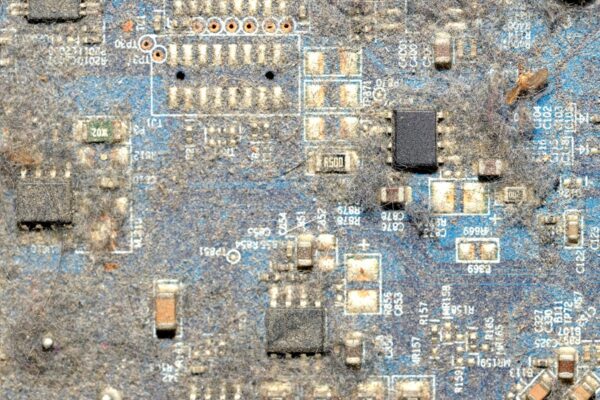

Electronics manufacturing is a constant war against two enemies: moisture and oxides. Baking at 125°C fights moisture but aggressively feeds oxidation. If your components have an OSP (Organic Solderability Preservative) finish, a high-temperature bake will destroy that protective coating. The organic layer breaks down, exposing the copper underneath to the hot air. By the time you pull those parts out, the leads or pads may look fine to the naked eye, but they have formed a thick oxide layer.

When these oxidized parts hit the SMT line, the flux in your solder paste will struggle to break through that oxide barrier. You will see wetting issues, head-in-pillow defects on BGAs, or weak solder joints that fail drop tests. You have essentially traded a moisture defect (popcorning) for a solderability defect (non-wetting). For components with Tin/Lead or pure Tin finishes, the risk is lower but still present, especially for fine-pitch parts where intermetallic growth can degrade joint reliability.

The only technically sound way to salvage wet components with sensitive finishes is the “Low-Temp Bake.” This usually means 40°C at less than 5% Relative Humidity (RH). It is painfully slow. We are talking about bake times measured in weeks, not hours—sometimes up to 79 days for thick packages (see Table 4-1 in the standard for the dizzying array of thickness-vs-MSL variables).

But 40°C is gentle. It drives the water molecules out without accelerating the chemical reaction that causes oxidation, preserving the solderability of the leads. If you are dealing with expensive silicon or hard-to-replace vintage parts, patience is the only engineering control that works.

Floor Life and the “Reset” Myth

Once the parts are dry and on the floor, the clock starts ticking. This is the “Floor Life”—the allowable exposure time defined by the component’s Moisture Sensitivity Level (MSL). An MSL 3 part gives you 168 hours. An MSL 5a part gives you only 24 hours.

There is a persistent myth on many production lines that you can “reset” this clock by simply popping the reel back into a dry cabinet for a few hours. This is false. A dry cabinet (keeping parts at <5% or <10% RH) only stops the clock; it does not rewind it. If an MSL 5a part is out for 10 hours, and you put it in a dry box for the night, it still has 10 hours of accumulated exposure when you take it out the next morning. It does not go back to zero.

To actually reset the floor life to zero, you must bake the part according to the standard. And as we just established, baking is a destructive process that eats into the component’s solderability budget. You cannot bake a part indefinitely; usually, you get one shot before the leads are too degraded to solder reliably.

This requires a level of process discipline often missing in high-mix environments. Operators must log the time out and time in with religious accuracy. If a reel is left on a feeder cart over the weekend because someone forgot to scan it back into the dry tower, you cannot “guess” that the humidity was low. You have to assume the worst-case scenario. If the facility humidity spiked to 60% RH while the lights were off, those parts are now suspect.

The Cost of Vigilance

Implementing a strict moisture control lane—inspecting HICs properly, refusing to accept “lavender” dots, and insisting on low-temp baking for sensitive finishes—will make you unpopular. It slows down receiving. It delays production runs while parts sit in a 40°C oven for a month.

But consider the alternative. A single moisture-induced delamination in a BGA is often undetectable until the board is fully assembled and powered on. Or worse, it passes the factory test and fails in the customer’s hands when thermal cycling propagates the micro-crack. The cost of scrapping a fully populated PCBA, or handling a field recall, dwarfs the cost of a dry cabinet or a schedule delay. In MSL control, paranoia isn’t a character flaw. It’s a prerequisite for yield.