A consigned kit can arrive looking tidy: boxes nested, reels bagged, labels crisp. That’s the trap. In a receiving cage, a reel with a third-party label sitting on top of a partially peeled manufacturer label turns the whole job into an argument about which sticker counts as “truth.” This is where a build is either protected or quietly gambled.

In two contract manufacturing environments—one ISO 13485 shop near Minneapolis and one high-mix industrial line in Wisconsin—the pattern is the same: the expensive failures are rarely the obviously wrong parts. The expensive failures are the parts that are “close enough” to load into a feeder without a fight.

In 2019, a run died the slow death that teams always misdiagnose at first: 0402 1% resistors placed cleanly, reflow looked fine, and then ICT yield cratered in a pattern that smelled like design trouble. But it wasn’t design—it was identity. The reel label said 10k, the BOM called 100k, and the shop’s internal barcode mapped to “resistor 0402 1%” with no value. Thousands of placements later, nobody could prove what value was actually on the tape without doing destructive-level work or a rework slog under a microscope. Roughly 1,800 boards went through hand rework, pads lifted, scrap piled up, and the internal cost landed around $28k before the customer even saw the whole blast radius.

No line load until identity is proven.

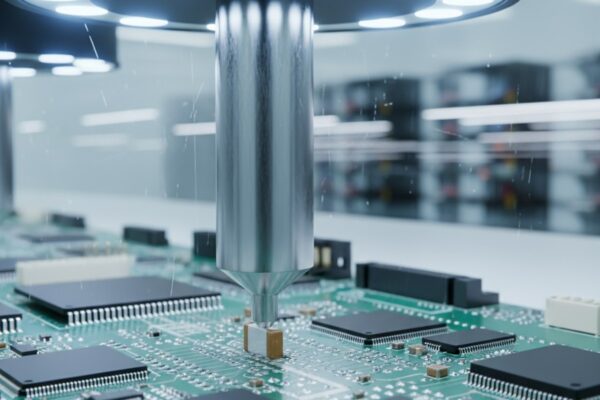

That line sounds rigid until you trace the mechanism: once a feeder is loaded and a placement machine is running at tens of thousands of components per hour, ambiguity compounds. Receiving can spend minutes to stop a build from consuming days. We need to define what “proven” means in practice—without turning receiving into a science project.

How Wrong MPNs Turn Into Line-Down Events (Mechanism Trace)

Start at the dock. A box arrives with customer-supplied material. Somebody checks a packing slip, counts bags, and scans a barcode into an ERP or spreadsheet. Then the parts get staged, kitted, walked to the line, loaded into feeders, placed, and reflowed. Only then do the real costs begin to multiply—because every downstream station assumes upstream identity was correct.

That 2019 resistor incident followed the most common path. The incoming kit looked “reasonable” because it had labels and the parts were passives, which are often treated as low drama. The build started, placement was fast, and the first clear signal came late: ICT failures consistent enough to look like a design margin issue. The team burned hours in the usual places—test engineering time, line-side debate, emails—before someone pulled the reel and asked a basic question that receiving should have answered: does this reel’s full manufacturer part number (not an internal house number) match the customer BOM line item? By the time the answer came back “no,” the cost was no longer a receiving problem; it was two shifts of microscope work and a schedule crater.

A wrong MPN isn’t just a wrong value passive. The 2021 version of the same movie is a QFN regulator that fits the footprint and passes first article visual inspection. The part “matches” at a glance: same body size, same pin count, neat label. Then functional test shows abnormal current draw, brownouts, and behavior that looks like design instability. Engineering time gets dragged into a failure that isn’t technical. In that case, the difference lived in the suffix and in assumptions about pin behavior and thermal pad recommendations. A buyer sourced an alternate under allocation pressure, a kit got labeled as the original, and receiving had no trigger to stop an engineering decision from being made in the dark.

Teams often reach for the wrong comfort here. They want to treat receiving as paperwork and move the risk to test, because test feels “real.” But test isn’t designed to prove identity; it proves performance against expected behavior. If the wrong part produces plausible behavior for a while, the escape can survive AOI, ICT, and even functional test, only to fail under field conditions not represented in the fixture. The earlier interception point is boring on purpose: confirm identity before the feeder loads.

A related schedule failure hides behind a polite phrase: “The kit is basically complete.” In 2023–2024, the same ticket tag showed up repeatedly—“kit incomplete”—because kits arrived 99% complete and teams wanted to “just start the build” while a missing connector or specialty LDO was in transit. That move creates half-built WIP, repeated changeovers, and a planning mess that gets blamed on manufacturing. It also creates a temptation to load whatever is on hand and “sort it later,” which is how ambiguous reels end up in feeders. Completeness gating protects the schedule rather than just adding bureaucracy. If the missing item is on the critical path, the honest option is a disposition decision, not optimism.

So the receiving gate has to do two things at once: prevent wrong MPNs from entering the line, and prevent partial kits from turning the floor into a WIP parking lot. Both problems share the same root: ambiguity tolerated at intake becomes chaos downstream.

The Three Claims Receiving Must Prove (and the Two-Cue Rule)

Receiving is not a single check. It involves three distinct claims that teams routinely collapse into one “looks fine” moment: identity, orientation, and condition. Each claim needs evidence, and the minimum viable control is two independent cues for each. Two labels printed by the same repacker are not independent. A barcode scan that only maps to an internal part number is not independent of the label it was derived from.

This guide skips basic SMT flow definitions—feeders, reflow, AOI, ICT—because the audience already lives in that world. The point here is how a receiving team proves the right thing, early enough that the line cannot accidentally convert uncertainty into labor and scrap.

Identity is the claim that the part is the part: the manufacturer MPN including suffix, and the correct revision/variant where applicable. The suffix is where the landmines live—temperature grade, lead finish, RoHS status, packaging code, and sometimes functional differences that are not visible on the body. The question that keeps showing up in real email threads is some version of “Do we need the full MPN?” or “Can we omit the packaging code?” The operational answer is simple: if the customer BOM lists a full MPN, receiving must match the full MPN. If a consigned label truncates the suffix, that’s not “close enough”—it’s a hold trigger. In 2021, a QFN that “fit” still failed functional because the variant assumption was wrong. The two-cue identity proof typically requires (1) label text/barcode reconciled to the customer BOM/AVL and (2) a second cue not derived from the same label—manufacturer label beneath a repack, a datasheet mapping that confirms the package and function, a top-mark sample under a USB microscope, or traceable franchised distributor documentation with lot/date codes.

Orientation is a different claim. A part can be the correct MPN and still be loaded wrong. The 2018 diode incident in an ISO 13485 environment looked like a soldering defect until someone put boards under a microscope and saw the diode band orientation didn’t match the assembly drawing. The consigned bag contained mixed diode variants with nearly identical markings, and the assembler followed the bag label, not the drawing. Instead of a speech about operator attention, the corrective action added a polarity sanity check at intake for polarized discretes and attached a photo log to the traveler. Orientation proof uses different cues: a package outline and pin-1 indicator versus the footprint/drawing, a diode band or cathode mark verified against the drawing, an LED polarity mark verified against the reel orientation and land pattern. This is also where small tools matter: a Dino-Lite-class microscope in receiving turns “it looked fine” into an actual cue.

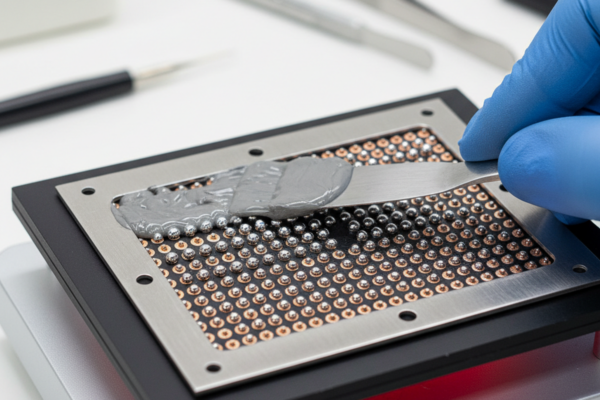

Condition is the third claim, and it is where teams try to treat physics like paperwork. Moisture sensitivity level handling is the most common example because it becomes an unprovable argument after shipment. In 2022, opened MSL parts arrived with no intact seal, no humidity indicator card (HIC), no desiccant worth mentioning, and no bake record. The easy path is to accept anyway because the calendar is screaming. The disciplined path is a red tag hold: either the customer proves floor life control (credible evidence, not vibes), or the material gets a documented reset plan—bake and reseal per JEDEC J-STD-033 concepts and the device datasheet’s bake limits. This is where the question “Do we really need the HIC card?” is rarely about the card. It is about who owns the schedule pain. Without condition evidence at receiving, nobody can defend the outcome later; every voiding or latent failure becomes a blame game.

A related comfort is “We scanned it, so it’s correct.” Scanning is useful, but it is not truth by itself. In 2020, a repackaged reel arrived with a crisp label and a barcode that matched the customer’s printed MPN, but the partially exposed manufacturer label didn’t align. The distributor’s traceability response was thin—effectively a PDF screenshot and a shrug. The receiving team sampled top marks and compared tape specs and physical dimensions against the datasheet; something didn’t line up well enough to load. The customer re-bought from a franchised channel. Barcodes aren’t the enemy, but a scan only provides a single cue. The second cue must come from somewhere else.

There is one nuance worth stating plainly: MSL handling specifics vary by component. JEDEC concepts create a structure (seal date, HIC response, floor life), but bake temperature/time limits are device-dependent. A receiving policy can require proof and a reset plan, but it should not pretend to have a universal bake recipe.

Once the two-cue rule is accepted, the next question becomes operational: what happens when cues disagree, or when the evidence packet is missing? That is escalation ladder territory.

Escalation Ladder: Accept, Hold, Reject (and Who Gets Pinged)

A receiving gate fails most often at the moment it needs teeth. Someone wants to “run it anyway,” and the organization lacks a shared script for what happens next. The ladder has three tiers—accept, hold for clarification, reject/return—and it needs objective triggers tied to identity, orientation, and condition.

A practical ladder starts with owners and time. A red tag hold is not a warehouse purgatory; it is a disposition with a service-level expectation, typically 24–48 hours, and a “stop the line load” rule while the hold is active. When a customer program manager pushes for speed, the ladder points to evidence. When sales wants smoothness, the ladder points to documented acceptance criteria. This is also how an organization defends itself in regulated environments: an ISO 13485 audit finding in 2020 was driven by undocumented receipt of customer material without documented acceptance criteria. The corrective action was not more signatures; it was a “hold until disposition” rule.

The triggers should read like reality, not theory.

- Identity triggers: missing suffix where suffix matters, internal house number with no mapping to manufacturer MPN, repack label covering manufacturer label with broken chain-of-custody, mismatch between label MPN and BOM/AVL.

- Orientation triggers: polarity ambiguous for diodes/LEDs/electrolytics, pin-1 indicator not verifiable against the footprint/drawing, mixed lots in bagged polarized parts.

- Condition triggers: MSL2/3+ devices with opened packaging and no HIC/seal date evidence, no bake log when required, damaged reels/tape that could misfeed or expose parts.

Two short rules keep the ladder honest. No heroics at the line. No “sorting it out” with undocumented line-side decisions. If the evidence is missing or contradictory, the correct place to resolve it is off-line, with the BOM owner or customer buyer, and with an ECO/deviation when an alternate is being accepted.

With the ladder defined, the next battle is cultural: the comfortable shortcuts that try to collapse the ladder back into “trust the scan” or “we’ll catch it later.”

Red-Teaming the Shortcuts (and the Minimum Honest Alternative)

The most seductive shortcut is barcode faith: “We scanned it, so it’s correct.” In shops with clean data models and intact chain-of-custody, scanning is powerful. In consigned kits, the chain is often fractured: repacks, house numbers, truncated labels, mixed date codes. The 2020 repack reel incident is the clean counterexample: a scan can be perfectly consistent with bad upstream labeling. Treat scanning as one cue. The second cue must be independent: manufacturer packaging evidence, datasheet mapping, top-mark sampling, or traceable franchised distributor documentation.

The second shortcut is test optimism: “We’ll catch wrong parts at test.” The 2019 0402 wrong-value incident shows why this is a coping story. ICT caught the problem after thousands of placements, when the line had already converted a simple receiving ambiguity into labor, schedule damage, and MRB/NCR paperwork. Even when test catches the issue, the cost is not the failing unit; it is rework, scrap risk, engineering time, and customer trust. Test is containment; receiving is prevention. These are different jobs.

The third shortcut is footprint thinking: “Same package equals same part.” The 2021 QFN look-alike failure makes this one expensive because it drags engineering into a non-engineering problem. A package match is not identity. The suffix matters, and alternates require documented approval—an ECO, a deviation, an updated AVL—before kitting. When a customer says “it’s the same,” the ladder’s job is to force that claim into a document, not to let it live as a hallway assurance.

A reasonable question remains: how much is enough? Specifically, how much sampling is “enough” for passives in sealed reels. There is no universal number that stays honest across channels, repack status, and historical performance. The pragmatic approach is risk tiers and history. Sealed manufacturer reels from a franchised channel with clean documentation can be sampled lightly—enough to confirm that the reel identity is real and consistent. Repacked passives, house-numbered reels, or any part family with recent NCR history deserve deeper checking. The point is not statistical purity; the point is to be explicit about why the sampling depth changed, and to tie it back to evidence and risk.

The fourth shortcut is the fantasy of 100% inspection. In 2017, leadership demanded full verification of everything consigned without adding headcount or time. Receiving got staffed with temps and a shared laptop, volume spiked, and the checklist became fiction—boxes stacked, signatures scribbled, line still starved. The fix was uncomfortable because it admitted limits: risk-based triage with hard escalation triggers. A smaller checklist that actually happens beats a perfect checklist that doesn’t.

One omission should be explicit: this guide is not an instruction set for counterfeit certainty, and it is not a lab-method playbook (no decap, no XRF claims). Those methods exist, and they have a place. But a receiving system should not pretend it can prove authenticity with certainty from a bench. The honest receiving contribution is chain-of-custody evidence and refusal to load ambiguous identity into a production run.

That leaves the practical question a customer and a CM can both answer: what does “good consignment” look like so receiving stays fast and the ladder stays mostly unused?

What “Good Consignment” Looks Like (So Receiving Can Stay Fast)

Good consignment isn’t just a vibe. It is a proof packet that lets receiving verify identity, orientation, and condition with minimal back-and-forth. The packet is also a way to reduce friction: a hold is less likely when the evidence arrives with the parts.

At minimum, a strong packet includes: a packing slip that maps line items to manufacturer MPNs (not just internal numbers), a certificate of conformance when applicable, a lot/date code list for traceability where required, and photos of labels for anything repacked or anything with suffix risk. For MSL-controlled devices, it includes intact packaging evidence (sealed bag or intact tray seal), an HIC card result, a seal date, and if the package has been opened, a documented bake/reset plan with dates and handling steps. For any alternate substitution driven by allocation or pricing, it includes a documented approval—an ECO or temporary deviation—and an updated AVL so receiving is not asked to validate an engineering decision by inference.

Each item exists for a specific claim. The BOM/AVL mapping and the full MPN address identity. The photos and top-mark sampling support independence of cues when labels are suspect. The orientation proof rides with drawings and traveler attachments for polarized parts and pin-1 verification on ICs. The MSL evidence proves condition in a way that can be defended later.

There is a legitimate edge case: true prototypes and very low-volume builds where the assembly is manual, the lot is controlled, and the customer accepts written risk. In that context, reduced checks can be rational—but “reduced” should still protect against the high-leverage failures. Identity and polarity checks for high-risk parts remain non-negotiable, and any reduced control should be documented as a choice, not as a quiet shortcut.

The practical payoff is schedule insurance. The recurring “kit is missing one line item” pattern shows what happens when optimism substitutes for disposition: WIP racks fill with half-built boards, changeovers multiply, and the floor becomes a calendar problem disguised as a manufacturing problem. A strict receiving gate feels slower in minutes. It is faster in weeks. And the earliest “no” is often the only version of “helpful” that prevents a build from turning into an argument nobody can win later.