The machine stops. Maybe it’s a high-speed industrial loom in a humid textile plant, or a medical monitoring cart in a quiet hospital ward. The symptom is always the same: a sudden, inexplicable loss of signal that halts operations. A technician opens the cabinet, taps the control box, and the system comes back to life. Engineers log it as a “software glitch” or a “ghost in the machine” and move on. They are wrong.

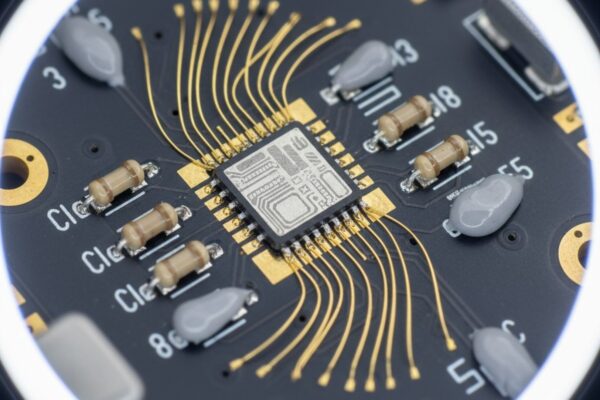

It’s rarely software. If you were to pull that circuit board and place the connector interface under a scanning electron microscope at 50x magnification, the ghost would reveal itself as a physical scar. This corrosion is born from a specific decision made months prior: mating a Gold-plated header with a Tin-plated socket. Supply chain shortages or a desire to shave fractions of a cent off the Bill of Materials (BOM) often drive this choice, but physics extracts a tax on that saving. You pay it in downtime, warranty claims, and the frantic replacement of “equivalent” parts that were never equivalent at all.

The Galvanic Trap

To understand why this failure is inevitable, look at the fundamental chemistry. Gold and Tin live in different neighborhoods on the galvanic series chart. Gold is a noble metal; it doesn’t oxidize. It remains conductive and inert essentially forever. Tin is a base metal. It wants to oxidize, forming a thin, hard skin of Tin Oxide (SnO2) almost immediately upon exposure to air.

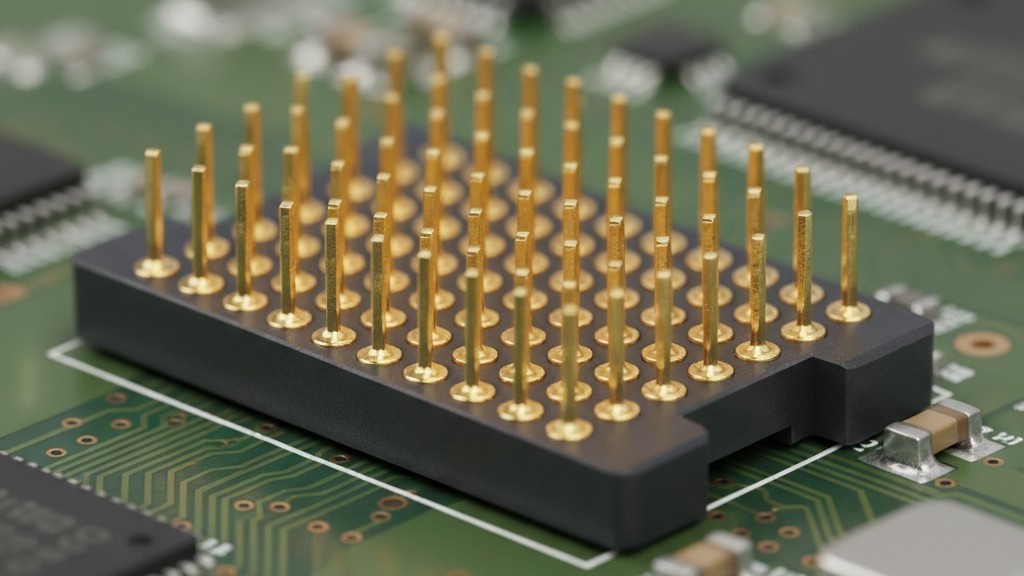

When you mate these two metals in a connector system—say, a standard 0.100″ pitch header from a series like Molex C-Grid or TE AMPMODU—you create a galvanic potential. The difference in electrode potential between Gold and Tin is approximately 0.4 volts. Add even minimal humidity, and that potential difference turns the connector interface into a small battery. The Tin becomes the anode and begins to corrode at an accelerated rate.

Designers often try to cheat this reality. A common question in design reviews is whether “Gold Flash” (a very thin layer of gold, often under 0.1 microns) is enough to mate with Tin. The assumption is that some gold is better than none. But Gold Flash is often porous. It allows the underlying nickel or copper to migrate through, creating complex intermetallic corrosion products that are even harder to predict than a pure Tin-Tin interface. The chemistry is unforgiving: if the plating systems do not match, the interface is unstable the moment it leaves the factory.

Yet, the battery effect alone rarely kills the signal immediately. If the connector were perfectly stationary, sealed in a block of epoxy, it might conduct for years despite the galvanic mismatch. The true killer requires a second accomplice: motion.

Fretting: The Engine of Destruction

We call this Fretting Corrosion. It isn’t caused by large, visible movements like unplugging and replugging a cable. It thrives on micro-motions—movements measured in micrometers—that occur while the connector is ostensibly “locked” in place.

Vibration often gets the blame—the hum of a factory floor or the rumble of a vehicle chassis. But in many cases, the culprit is simply thermal cycling. Consider a PCB mounted inside a plastic enclosure. As the device heats up during operation and cools down at night, the plastic housing and the FR-4 fiberglass of the PCB expand and contract at different rates. This mismatch forces the connector pins to scrub back and forth against their mating contacts.

When a Tin contact mates with another Tin contact, this scrubbing is actually beneficial; it breaks through the oxide layer and exposes fresh, conductive metal. This is “self-cleaning.” But when a hard Gold header mates with a soft Tin socket, the dynamic changes. The hard Gold pin acts like a file. With every thermal cycle, it scrapes the soft Tin. The Tin oxidizes, and the Gold scrapes that oxide off.

Over time—perhaps 200 cycles, perhaps 2,000—this debris accumulates. Tin Oxide is ceramic-like: hard, brittle, and electrically insulating. It doesn’t fall away; it gets trapped in the contact interface. Under the microscope, this accumulation appears as a “Black Spot” in the center of the contact area. It looks like a pile of soot. Eventually, that soot grows thick enough to separate the metal surfaces entirely. The resistance of the connection doesn’t rise linearly; it spikes exponentially. One moment the resistance is 30 milliohms; the next, it is an open circuit.

There are exceptions. If a connector system is designed with massive normal force—think of a high-pressure gas-tight crimp or a bolted terminal—the pressure can punch through almost any oxide layer. But for the vast majority of board-to-board and wire-to-board connectors used in industrial and consumer electronics, the contact force relies on a small, stamped metal spring. It simply lacks the strength to crush the oxide debris generated by a Gold-Tin mismatch.

The Software Illusion

The most dangerous aspect of Fretting Corrosion is its intermittency. Because a pile of loose debris causes the failure, the connection is mechanically unstable. A slight vibration, a thermal shift, or even the percussive maintenance of a frustrated technician tapping the box can shift the debris pile just enough to re-establish contact.

This creates a wasteful pattern in engineering teams. The hardware fails in the field, but when the unit returns to the lab for “Bench Testing,” it works perfectly. Unplugging the unit to ship it wiped the contact clean, or the stable lab temperature prevents the thermal expansion that triggers the open circuit.

So, the hardware team signs off, and the blame shifts to firmware. Developers spend weeks writing “debounce” algorithms to filter out noise on input pins or adding retry logic to communication packets. They are trying to solve a physics problem with code. No amount of software debouncing can fix a localized high-resistance junction that is physically separating the signal path. You cannot code your way across an air gap.

Mitigation and the Lubricant Band-Aid

If a fleet of devices is already deployed with this mismatched plating, and recalls are financially impossible, there is only one reliable mitigation: lubrication. Specialized contact lubricants, such as Nyogel 760G, can be injected into the connector interface.

The lubricant serves two purposes. First, it seals the contact area from oxygen and humidity, slowing the galvanic corrosion. Second, and more importantly, it suspends the oxide debris. Instead of packing down into a solid insulating layer, the debris floats in the grease, allowing the metal asperities to push through and make contact.

However, relying on lubricant as a primary design strategy for a mixed-metal interface is a gamble. It creates a maintenance burden. It attracts dust. It eventually dries out. It is a band-aid for a wound that shouldn’t exist. The only time a mixed interface is acceptable is in consumer electronics with short lifespans—a mobile phone replaced in two years may not experience enough thermal cycles to build up the critical oxide mass. But for industrial, automotive, or medical equipment designed to last a decade, the lubricant will eventually fail, and the physics will resume its work.

The Verdict: Rules of Engagement

The economic argument for mixing platings is usually simple: “We have thousands of Gold headers in stock, but the Tin sockets are cheaper.” Or, “The supply chain is broken, and we can only get the Gold version of the header.” The savings might be pennies per unit.

Compare that saving to the cost of a single field failure. In an industrial setting, a truck roll to diagnose a stopped machine can cost $500 to $1,000. If the failure causes a production line stoppage, the cost can be thousands of dollars per hour. A failure rate of even 0.1% wipes out the BOM savings of the entire production run.

The rules of engagement are absolute. If the header is Gold, the socket must be Gold. If the header is Tin, the socket must be Tin. There is no “hybrid” solution safe for long-term reliability. The BOM is not a grocery list where ingredients can be swapped based on daily market prices; it is a definition of the electromechanical system. When you mix Gold and Tin, you are not saving money. You are building a timer.