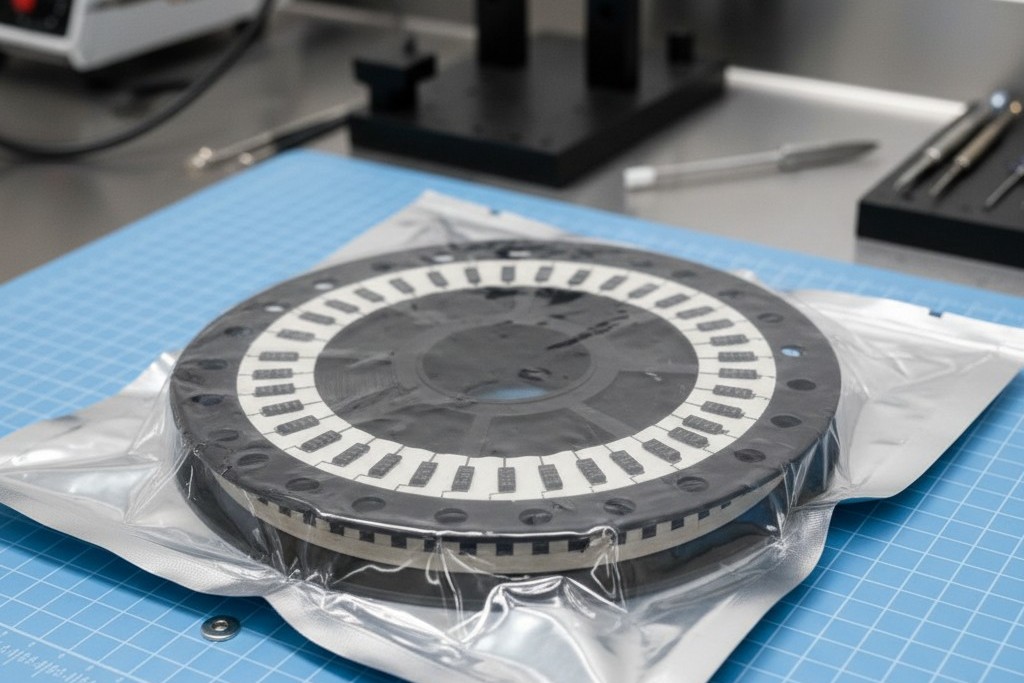

In electronics manufacturing, the most dangerous component is often the one that’s already been used. A full, vacuum-sealed reel arriving from a distributor like Digi-Key or Mouser is a known, safe quantity. But the moment that seal breaks and the reel hits a feeder, a clock starts ticking. When the run finishes and a partial reel remains, how you handle that leftover inventory determines whether the next production run yields functional boards or expensive scrap.

This isn’t about warehouse tidiness; it’s thermodynamics.

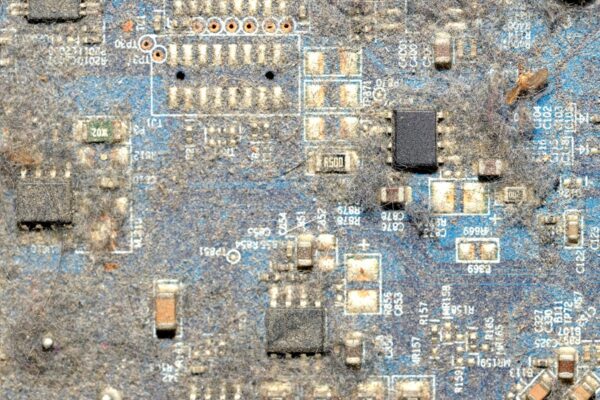

When a moisture-sensitive device—say, a BGA or a QFN—sits exposed to the ambient air of a production floor, its hygroscopic epoxy encapsulant begins to absorb water vapor. It acts like a sponge. If that component is later placed onto a board and sent through a reflow oven, the temperature spikes to 240°C or 260°C in seconds. The trapped water inside the plastic package doesn’t just get hot; it flashes into superheated steam. Since water expands roughly 1,600 times in volume when it turns to steam, the pressure inside that tiny component becomes explosive. The result is “popcorning”—internal micro-cracks, delamination of the die from the lead frame, and bond wire failures. You often can’t see this damage with the naked eye, but the board will fail.

The only defense against this physics is a rigorous, almost paranoid sealing protocol. The moisture barrier bag (MBB) isn’t just packaging—it’s a time capsule.

The Cumulative Clock

A persistent myth haunts many shop floors: that the “Floor Life” clock—the allowable exposure time defined by J-STD-033—resets the moment a part goes back in a bag. That is dangerous wishful thinking. The clock doesn’t reset; it merely pauses. If an MSL Level 3 component has a 168-hour floor life and sits on a feeder for 24 hours, it has 144 hours left. If it’s thrown into a loose bag with a weak seal for a week, diffusion continues, albeit slower. When it comes back out for the next job, it might already be dead stock.

This reality dictates how we handle partial reels the second they come off the pick-and-place machine. The gap between “End of Run” and “Vacuum Seal” is the single most critical variable in inventory preservation. In a high-humidity environment—think a Midwest summer where the shop floor hits 60% RH despite the HVAC fighting for its life—moisture ingress happens rapidly. Leaving a reel of high-value FPGAs on a cart “to be packed later” is essentially deciding to degrade the parts on purpose. The protocol must be immediate: the reel comes off the machine, the leader is secured, and it goes straight to the sealing station.

This strictness often confuses clients who supply their own materials. When we receive a consigned kit, we often have to break the client’s original seals to verify counts or load feeders. Once that happens, we own the moisture risk. We can’t simply tape the bag shut and hope for the best, nor can we rely on the client’s original packaging if it’s been compromised. We reseal everything according to our internal MSL protocols, regardless of how it arrived. If the part is open, the clock is ticking, and we are responsible for pausing it.

Standard diffusion rates assume a specific ambient environment, usually 30°C/60% RH. While a reel sitting in a bone-dry Arizona facility absorbs moisture slower than one in Ohio, relying on ambient luck isn’t a process. The protocol must assume the worst-case scenario to guarantee safety. If the vacuum seal isn’t tight enough to show the outline of the sprocket holes through the bag, it’s not a seal. It’s just a loose wrapper, and the clock is still running.

The Lie of the Reused Desiccant

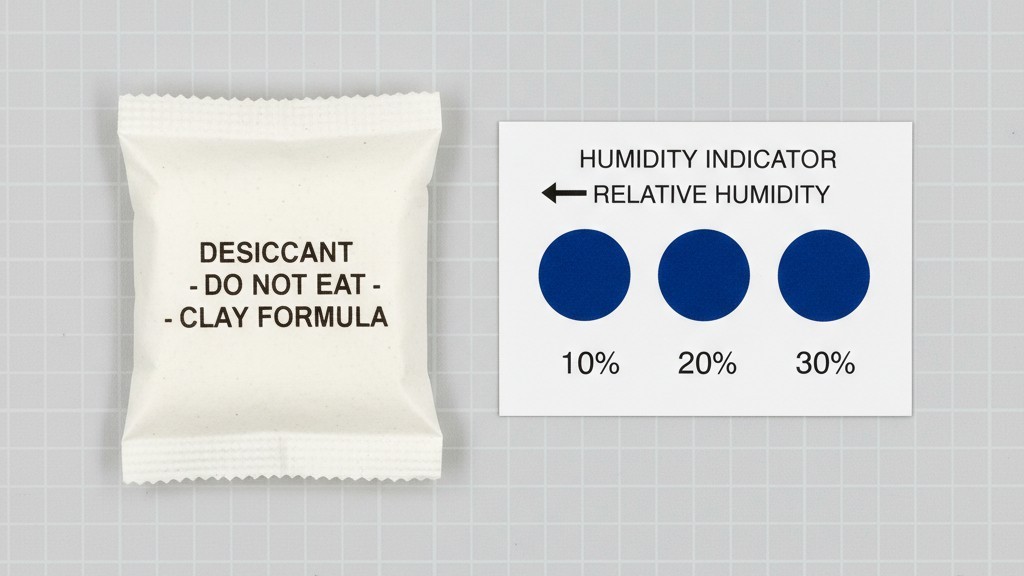

The most common failure point in partial reel storage isn’t the bag itself, but the chemistry inside it. Cost-conscious operations have a tendency to reuse the desiccant packet that came with the original reel. The operator pulls the reel out, tosses the packet on the bench, runs the job, and then throws that same packet back in with the partial reel.

That packet is likely dead.

Desiccant, whether silica gel or montmorillonite clay, has a finite capacity to adsorb moisture. Once it reaches saturation, it stops working. It becomes inert mass. Putting a saturated desiccant packet into a sealed bag is like putting a rock in the bag; it provides zero protection. In fact, if that packet absorbed moisture from a humid factory floor all day, sealing it inside the bag with the parts can actually lock moisture in, creating a localized humid environment right next to the sensitive components.

We employ a simple “rock test” for clay desiccants, but the only real verification is the Humidity Indicator Card (HIC). Every partial reel we seal gets a brand new, fresh desiccant packet and a fresh HIC. We don’t reuse them. The cost of a 4-unit desiccant pack from a reputable vendor like Clariant is measured in pennies. The cost of reworking a board with a delaminated $500 IC is massive. Saving forty cents to risk a forty-thousand-dollar production run is false economy.

Occasionally, facility managers ask if they can just use nitrogen dry cabinets instead of vacuum sealing. Dry cabinets are excellent for Work In Progress (WIP)—parts that will be used again within 48 hours. But you can’t ship a dry cabinet, and you can’t stack it on a warehouse shelf for six months. For long-term storage of partials, the vacuum bag is the only viable solution.

When a reel is pulled from inventory months later, the HIC is the source of truth. It’s the only honest thing in the warehouse. If the 10% spot has turned from blue to pink, the seal failed. The parts are suspect. No amount of arguing about logbooks or seal dates overrides the chemistry of the card.

The Baking Fallacy

The “Red Team” argument—the one we hear from junior technicians and schedule-pressured managers alike—is simple: “Why worry about bags? If the parts get wet, we can just bake them.”

This is a fundamental misunderstanding of electronics manufacturing. Baking isn’t a standard process step; it’s a rescue mission for a failure that has already occurred. And like most rescue missions, it comes with collateral damage.

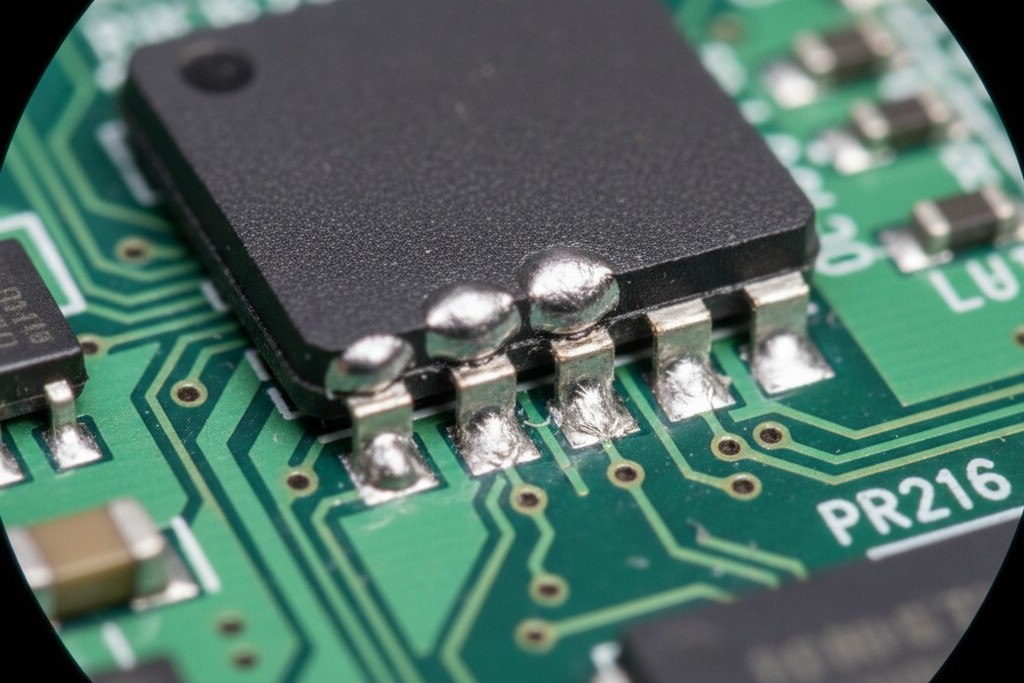

To drive moisture out of a plastic package, you have to heat it. Standard baking profiles often call for 125°C for 24 hours, or lower temperatures for much longer durations. While this does remove water, it also accelerates the growth of intermetallic layers between the copper lead frame and the tin/lead or gold plating. It promotes oxidation on the termination surfaces.

When you take that baked part and try to solder it, you often find the leads have oxidized to the point where the solder paste won’t wet. You’ve traded a moisture problem for a solderability problem. You might not get popcorning, but you will get open joints, head-in-pillow defects, or weak wetting that fails in the field. We see this specifically with QFNs and other bottom-terminated components where the connection is purely chemical.

For this reason, we don’t discuss baking as a “Plan B” for inventory. We view baking as a last resort for parts that have been mishandled, usually from gray-market sources. For our own partials, the goal is to never let them see the inside of an oven until they are on the board for reflow. I won’t list baking profiles here because I don’t want to encourage their use. The process relies on prevention, not remediation.

The Physics of Profit

Ultimately, the discipline of sealing partial reels is about protecting the yield rate. It is tedious work. It requires operators to stop what they are doing, fetch fresh materials, and wait for the vacuum sealer to cycle. It feels like downtime.

But when you look at the P&L of a manufacturing line, that “downtime” is actually an insurance premium. The cost of sealing a reel correctly is roughly one dollar in labor and materials. The cost of a single field failure caused by a micro-crack in a moisture-sensitive component can wipe out the margin for the entire batch. Physics doesn’t care about your deadline, and it doesn’t care about your savings on plastic bags. It only respects the barrier.