You spend months optimizing signal integrity. You fight for every decibel of noise floor. You validate the thermal management of the FETs with elaborate heatsinks and airflow models. Then, at the very end of the line, you hand the board over to production to be potted. They mix a two-part epoxy, pour it into the housing, and set it on a rack to cure.

That is exactly where you lose the unit.

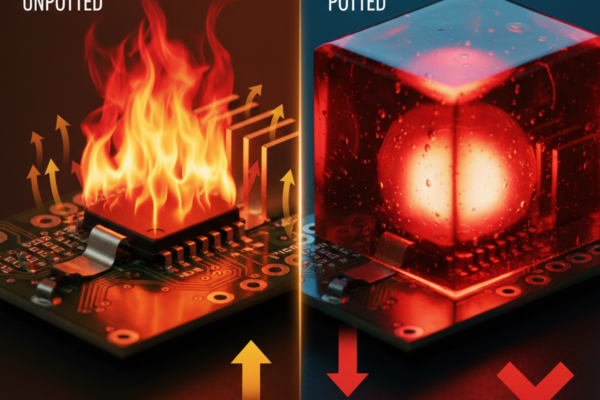

It wasn’t an electrical short or a firmware bug. It was a failure to respect the violence of the chemical reaction you just initiated. Potting isn’t simply “drying” or “hardening.” It is an exothermic polymerization event. When you mix Part A and Part B, you start a fire that burns chemically rather than oxidatively. If you don’t manage that fire, the internal temperature of the potting mass can easily exceed 180°C—cooking your electrolytic capacitors, desoldering resistors, and cracking ferrite cores before the unit even leaves the factory floor.

The Physics of Angry Chemistry

The fundamental mistake most engineers make is assuming the temperature inside the potting cup matches the curing oven or the room. This is dangerously wrong. The reaction between an epoxy resin and its hardener releases energy. In a thin film, like a conformal coating, that heat dissipates into the air instantly. The reaction stays cool. But potting is a bulk process. You are pouring a thick, insulating blanket of plastic around a heat source that is the plastic itself.

This creates a runaway thermal loop driven by the Arrhenius equation: for roughly every 10°C increase in temperature, the reaction rate doubles. As the epoxy reacts, it generates heat. That heat cannot escape because epoxy is a natural thermal insulator. So the heat stays in the core, raising the temperature. The higher temperature makes the remaining epoxy react faster, generating more heat, driving the reaction even harder. It is an engine that accelerates itself until it runs out of fuel or melts something.

You might think you’re safe because you’re using a “Room Temperature Cure” formulation. Do not let the terminology fool you. “Room Temperature” just means you don’t need an external oven to kickstart the reaction; it does not mean the material stays at room temperature. In fact, fast-setting “5-minute” epoxies are often the most violent offenders. I have seen a technician mix a 5-gallon pail of fast-set epoxy, intending to ladle it out over an hour. Within ten minutes, the bucket was a smoking volcano that melted its own plastic liner and fused to the concrete floor. The physics of mass effect does not negotiate.

Don’t confuse this with a mixing error. Yes, if you mix the ratio wrong, you get a gummy, soft mess that never cures. That is a failure, but it’s a “safe” failure. The far more dangerous scenario is when you mix it perfectly, but underestimate the mass. A 100-gram cup might peak at a manageable 60°C. That same material, poured into a 2-liter reservoir for a high-voltage power supply, has a vastly lower surface-area-to-volume ratio. It can’t shed the heat. The core temperature spikes, and suddenly you have a reactor vessel sitting on your workbench.

Silent Killers: How Components Die

When the exotherm spikes, the damage is rarely visible on the outside. The surface of the potting might look pristine, perhaps a little warm to the touch. But deep inside, where the heat had nowhere to go, the environment has become hostile.

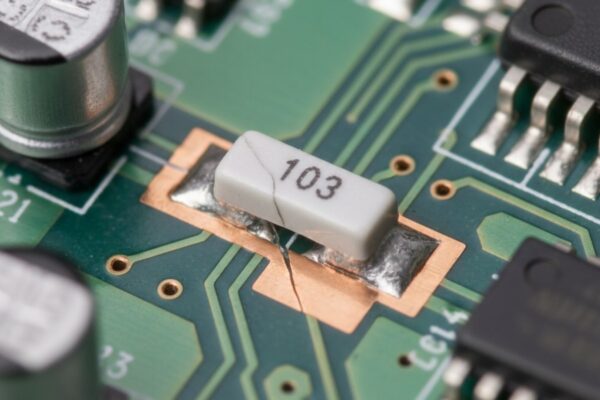

Take a standard surface-mount assembly. You have 0402 capacitors soldered to FR4. As the epoxy exotherm hits its peak—let’s say 160°C—the board is hot, but the solder holds. However, as the reaction finishes, the epoxy hardens into a rigid solid. Now the entire mass begins to cool down to room temperature. Now you face the second killer: Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) mismatch. The epoxy shrinks as it cools. The PCB shrinks at a different rate. The ceramic capacitor doesn’t shrink much at all. The result is a massive shear force applied directly to the solder joints. I have seen capacitors ripped off their pads, or worse, cracked internally so they pass a continuity test today but fail open after a month of vibration in the field.

Magnetic components are even more vulnerable. Ferrite cores are brittle ceramics that rely on specific crystalline structures to maintain inductance. When you encase a transformer in a hard, unfilled epoxy and let it exotherm, you are essentially subjecting it to a thermal shock followed by a crushing mechanical vice. If you stand in a quiet production bay after a batch of power supplies has been potted, you can sometimes hear the faint tink tink sound of ferrite cores cracking inside the cooling resin. You won’t see it, but your inductance values will drift out of spec, and your power supply efficiency will tank.

Batteries are the highest stakes game here. If you are potting 18650 cells for a prototype pack, you are playing with fire—literally. Standard structural epoxies can easily hit temperatures that melt the PVC shrink wrap on the cells (usually rated for ~80°C to 100°C). Once that insulation melts, the cells short against each other or the case. I’ve seen packs that didn’t explode but were effectively dead on arrival because the thermal event during potting compromised the separators.

The Datasheet Lie

So why didn’t the datasheet warn you? It probably did, but you have to know how to read the fine print. Vendors want to sell you epoxy, so they list the “Peak Exotherm” in the most favorable conditions possible.

Look closely at the test method. Usually, it cites ASTM D2240 or a similar standard, and somewhere in the footnotes, it will specify the mass of the test sample. It is almost always 100 grams. 100 grams is a coffee cup. It is not a 55-gallon drum or a deep-section high-voltage housing. Relying on that number for a large-volume pour is like assuming a campfire and a forest fire have the same thermal output because they are both burning wood.

Furthermore, vendors often test in a container that conducts heat well, or spread the material out in a thin layer. In your product, you might be pouring into a plastic housing (insulator) around a PCB (insulator). The heat has no escape path. The datasheet is not a guarantee of performance; it is a baseline measurement taken in “Lab World.” You live in “Production World,” and the scaling factors here are non-linear. You cannot predict the exact peak exotherm of your specific geometry using a linear extrapolation of the vendor’s data.

Mitigation: The Chemistry Pivot

If you are seeing dangerous heat levels, your first lever is chemistry. You need a material that acts as a heat sink rather than just a heat generator.

This usually means moving to a “highly filled” system. These epoxies are loaded with thermally conductive fillers like alumina or silica. The fillers do two things: they conduct heat out of the core to the surface, and they displace the reactive resin volume. If a pot is 50% filler by weight, that’s 50% less chemical reaction happening per cubic centimeter. The trade-off is viscosity—filled materials are like pouring cold honey—but they will keep your peak temps down.

You might also consider leaving epoxy behind entirely. Silicones and urethanes generally have much lower exotherms. Silicones, in particular, are very forgiving on the cure temperature and put almost no stress on components because they remain soft (Low Shore A hardness). However, before you swap to silicone, remember that silicone oils migrate everywhere and can cause adhesion failures in painting or coating processes downstream. It solves the heat problem but introduces a contamination risk you must manage.

Mitigation: The Process Pivot

If you must use a rigid epoxy and you have a large volume to fill, you cannot fight the physics of the reaction. You have to change the geometry of the pour.

The most reliable (albeit expensive) fix is the “Two-Stage Pour.” You fill the unit halfway, covering the less sensitive components or just the base. You let that layer gel and cool. Then you pour the second half. By splitting the mass, you cut the exotherm spike significantly. The heat from the second pour can also dissipate into the first layer, which acts as a heat sink.

Production managers hate this. It doubles the handling time and increases work-in-progress (WIP) on the floor. They will ask if they can just put the curing racks in a refrigerator to cool them down. This is risky. If you cool the outside too fast while the inside is reacting, you create a thermal gradient that leads to massive internal stress and cracking. You can use fans to move air, but active refrigeration often causes more problems than it solves, including moisture condensation on the uncured surface which can inhibit the reaction.

The Only Truth is the Thermocouple

You can model this, you can read datasheets, and you can argue with the vendor reps. But there is only one way to know if you are cooking your board.

You have to sacrifice a unit.

Take a production-intent board and housing. Drill a hole in the case or sneak a probe in before pouring. Embed a K-type thermocouple directly into the center of the largest mass of epoxy, or tape it to the body of your most sensitive capacitor. Pour the potting compound and hook the probe to a data logger. Walk away and let it cure.

When you come back, look at the curve. If you see a spike hitting 140°C or 160°C, you have your answer. No amount of theoretical debate overrides the data from the thermocouple. That chart is your license to demand a process change, a material switch, or a redesign. Until you have that line on a graph, you are just guessing, and physics is waiting to prove you wrong.