The moment is usually unremarkable. A programming bench with a Windows 10 box. A batch script sitting on the desktop. A USB stick with a Sharpie label that says something like “PROD FW.” Night shift is 40% contractors, the supervisor is watching takt time, and everyone is doing what keeps units moving.

Then one small thing happens—an operator walks away with that stick in a pocket with earplugs and a badge clip—and the real problem appears: nobody can prove what did or didn’t leave the building.

That proof gap is the whole game. Secure programming and key injection during PCBA isn’t just a line step. It is a controlled boundary that produces evidence per serial.

1) Stop Asking “How Do We Lock This Down?” and Ask “Where Is the Boundary?”

If the factory is treated as a trusted room, secrets will behave like tools: they will drift to wherever work is fastest. That isn’t a moral judgment about operators; it’s simply what happens when quotas meet friction.

The boundary is rarely the whole building. It’s almost always smaller and more explicit: a caged programming station with badge access, a locked-down OS image, a constrained path for artifacts to enter, and a defined set of roles who can initiate or approve changes. Inside that boundary, secrets can exist in controlled forms. Outside it, they shouldn’t.

This is where teams often jump to vendors, HSMs, “secure flashing services,” or a cloud KMS. That’s backwards. The first question is simpler and more uncomfortable: what is allowed to cross into the programming boundary, and in what form?

The second question is operational: where does evidence get created? If there is no per-serial trail that binds station identity, operator identity, time, and injected artifacts, it will eventually turn into a two-week forensic reconstruction rather than an engineering discussion.

And for anyone tempted to say, “Our EMS is trusted”: trust can be a contract term plus controls, logging, and role separation. Trust as a feeling is not an audit answer, and it won’t satisfy an incident response team.

2) Name the Secrets (Yes, Explicitly) and Tie Each to a Failure Mode

“Secrets” gets treated like a single bucket, which is how teams end up applying the wrong control to the wrong thing. In this environment, it helps to name what actually matters:

- Production signing keys: The update channel’s spine. If they leak, the blast radius isn’t just one batch of boards; it’s every device that will trust that signature in the field.

- Device identity keys or device certificates: What makes units unique. If duplication happens, it looks like a crypto bug until it turns into a recall-shaped argument with support and QA.

- Firmware images and provisioning bundles: The customer IP everyone is anxious about, plus the exact build that has to match the ECO reality of the week.

- Calibration or configuration secrets: Sometimes low value, sometimes not—especially if they unlock features or encode customer-specific behavior.

Now attach failure modes, because this is where security and quality converge. Leaks happen, but “wrong image shipped” is often the first real incident. A station cached artifacts locally. One shift used new bootloader config, another shift used the old. There was logging, but no integrity and no time sanity. The organization couldn’t prove what happened per serial; it could only guess and rework.

Be blunt here: if per-serial correctness is not provable, the line will eventually ship a ghost.

3) Evidence Is a Product Feature: Per-Serial Proof Without Handing Over the Image

Treat the secure programming setup as a service with an output: evidence. The line isn’t just producing programmed devices; it is producing a verifiable history of how each serial became what it is.

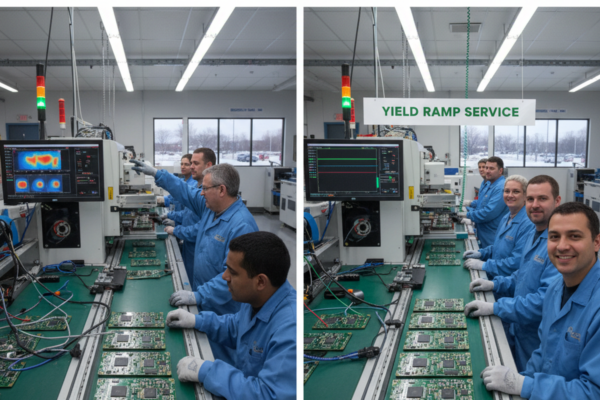

This is why the “clean audit after building an ugly process on purpose” works as a pattern. The controls weren’t elegant. They were boring and explicit: locked programming stations, a two-person key ceremony using dual smart cards (PIV on YubiKey 5), daily log export to WORM storage, and documented time sync (NTP hierarchy written down, enforced, and checked). The auditor’s questions were predictable: who had access, what was logged, how integrity was ensured, and how the right image was injected per device without giving the factory the crown jewels.

The solution wasn’t “show the firmware.” It was “show the proofs.”

A practical proof pattern looks like this:

A per-serial provisioning manifest exists as a first-class artifact. It includes the device serial (or device-derived identity), the firmware image fingerprint (a SHA-256 digest, not the full binary), identifiers for key handles injected or used (not exportable key material), station identity, operator identity, a timestamp tied to a sane clock, and a signature from the programming service. The factory can verify it. QA can use it. Security can defend it. Incident response can reconstruct without heroics.

That manifest also changes how the factory relationship feels. The EMS doesn’t need Git access to validate. It needs the signed bundle plus verification metadata, and a tool that can read a device measurement and compare it to an allowlist of hashes. Verification-only is different from disclosure.

How would anyone prove a key was never copied?

This is where “logs are enough” collapses, because most factory logs are activity records, not evidence. If logs can be edited, if operator identity is shared (a single local admin password, or a shared workstation account), if timestamps drift because time sync is informal, then the best the organization can do is tell a plausible story. That isn’t proof. Evidence requires integrity properties: tamper-evidence, identity binding, time sanity, and retention that survives the moment an incident makes people defensive.

Audit expectations vary by industry—medical, automotive, telecom, defense all pull in different directions—and it’s worth confirming what your sector expects. But the baseline “evidence product” is broadly defensible: per-serial manifests, signed digests, and logs designed to be trusted by someone who wasn’t in the meeting.

4) What Actually Runs on the Line: A Secure Programming Service Blueprint

Most real failures cluster at the programming station, because that is where engineering intent hits factory reality. A station that “worked” for months can become a chaos generator after a Windows update changes driver signing behavior. Suddenly the USB programmer fails intermittently. Operators develop folk remedies: reboot twice, swap ports, try the other cable. The process still “runs,” which is the most dangerous state, because it produces units and uncertainty in the same motion.

A blueprint that respects throughput starts by treating stations like infrastructure, not hobbies:

The station image is immutable in the ways that matter. Updates are controlled, tested, and promoted, not applied ad hoc. Local admin isn’t shared. USB device policies are deliberate. Network paths are constrained. If artifacts are cached locally, that cache is part of the controlled system, not a convenience drift. This isn’t paranoia; it’s repeatability. The station should be reconstitutable from versioned configs and station build records.

Then the programming flow is designed as a set of allowed moves:

A signed release bundle enters the boundary through a controlled path. The station verifies bundle signatures and image digests against an allowlist. Non-exportable keys are used via handles, not copied blobs. The device is programmed, then measured or attested, and the result is written into the per-serial manifest. The manifest is signed and exported to retention (often daily) in a way that creates a tamper-evident record.

Controls sound like “security” until the line asks the throughput question, which is valid: what does this do to minutes per unit and station count? The honest answer is that it changes station design. It may require pre-staging artifacts, batching operations, or adding a station during ramp. But throughput is a design input, not a veto. Weakening controls because “it slows the line” is how organizations purchase a future incident.

There is a related question that surfaces as soon as volume and SKUs grow: identity binding.

Label rolls get swapped. It happens at shift change, especially when temp staff are filling benches. In one real case, devices returned from the field with certificates that didn’t match printed serial labels, and the team’s first instinct was to blame cryptography. The root cause was tape and fatigue: two similar SKUs, two label rolls, one swap. Provisioning bound keys to whatever serial the station software was told. QA relied on spot checks. The evidence didn’t exist to catch it before shipping.

The fix isn’t more fear about labels. The fix is an independent anchor: read a hardware identifier from the device (or inject a secure internal serial) and bind the printed label as a derived artifact, not the source of truth. Add a mismatch alarm at the station: if device-reported ID and label-provided serial diverge, the line stops and logs it. It feels harsh until the first time it saves a batch.

At this point the blueprint has established the station as the choke point and the manifest as the evidence output. The next choke point is key custody and promotions—because this is where convenience ideas sneak in.

Hardware roots of trust and attestation maturity vary wildly by MCU/SoC and by supply constraints. A blueprint should still work without “fancy” attestation by leaning harder on station controls and evidence artifacts, and then upgrade when the hardware story improves.

5) Key Custody and Promotion Gates: Convenience Is Where Leaks Live

Offline key handling isn’t nostalgia. It is blast-radius reduction. Online systems create invisible coupling: credentials, network paths, support staff, and “temporary” access patterns become implicit key custodians. When the threat model includes insiders, churn, or just tired people on deadline, that coupling becomes a liability.

A familiar moment triggers the wrong architecture: release night chaos. Someone proposes storing the production signing key in a CI secret store “just for a week” to automate. It sounds reasonable because it reduces immediate pain. It is also a classic mechanism for creating a shadow exfil path through logs, runner images, support access, backups, and debug tooling.

This is where a mechanism trace is more useful than an argument. If a signing key lives in CI—even a “secure” one—where can it land? In ephemeral runner images that get reused. In CI logs or debug output. In the hands of whoever can change pipelines. In the hands of platform support under break-glass. In backups and incident snapshots. After the fact, can anyone prove it was never copied? Usually not. That is the proof gap again, but now attached to the update channel.

The rebuild that preserves automation without exporting keys is a promotion gate: artifacts are signed in a controlled environment using non-exportable keys (HSM, smart card, or equivalent, with a clear threat model), and the act of promoting a release bundle into production is recorded with role separation—2-of-3 approvals, tickets that show who approved what, and evidence artifacts that follow the bundle downstream. The factory receives signed bundles and verification metadata, not key material and not mutable pipelines.

A different adjacent request shows up in NPI ramps: “Our EMS needs the source to debug faster.” This usually isn’t malice; it’s a negotiation shortcut. The underlying need is a tight debug loop and observability. The answer is to say no to repo access and yes to the underlying need: provide a debug bundle with controlled contents, decide how symbols are handled, define reproduction procedures, and keep programming packages signed with clear provenance. It turns fear into an operational agreement.

Legal and regulatory expectations vary here, and it is worth involving counsel for export controls and data handling terms. But the security position is straightforward: the factory needs proofs and controlled observability, not ownership of IP.

6) Exceptions Are the Test: Rework, Scrap, RMAs, and Night Shift

Controls that only work during the happy path aren’t controls. The factory reality is exceptions: rework benches, reflashes, scrap disposition, station failures, ECO churn, and the night shift where staffing is thinner and shortcuts are more likely.

This is where evidence design pays for itself. If a unit is reworked, the manifest should show it as a new event tied to the same device-derived identity, with station identity, operator identity, and the exact bundle used. If a station goes down and another is used, the artifacts shouldn’t become “whatever was on that other box.” If scrap is reintroduced by mistake, the system should be able to catch it.

It’s also where time sync becomes more than a compliance checkbox. When timestamps are inconsistent across stations, forensic reconstruction turns into a human memory exercise. When they are consistent and tamper-evident logs are exported daily to WORM retention, an incident stops being a mystery and becomes a trace.

A secure programming process is what happens when the line is under pressure. If the evidence disappears during chaos, the organization will eventually ship ghosts and only learn about them through customers.

7) Baseline vs Mature: What to Do Without Turning the Line Into a Museum

There is a minimum viable secure posture that doesn’t require a perfect toolchain:

Lock down programming stations and treat them as the boundary. Stop shared local admin and shared credentials. Use signed release bundles and a verification step that checks cryptographic fingerprints (hash allowlists) before programming. Produce per-serial manifests that bind image identity, station identity, operator identity, and time, and export logs into retention with integrity properties. Design an explicit exception path for rework and reflashes.

A mature end-state grows from that baseline rather than replacing it: stronger separation of duties for promotions, non-exportable key custody with ceremonies that auditors can understand, attestation where hardware supports it, and measured weekly indicators that show whether the boundary is behaving. Those indicators aren’t abstract: exceptions per week, station drift incidents, log gaps or time sync failures, and the number of emergency “break-glass” events.

The final check is still the same, and it’s not philosophical. When someone asks, “Are we secure on the line?” the only meaningful response is evidence: per-serial, provable, boring.

If an organization cannot prove what happened, it isn’t running secure programming. It is running hope with a batch script.