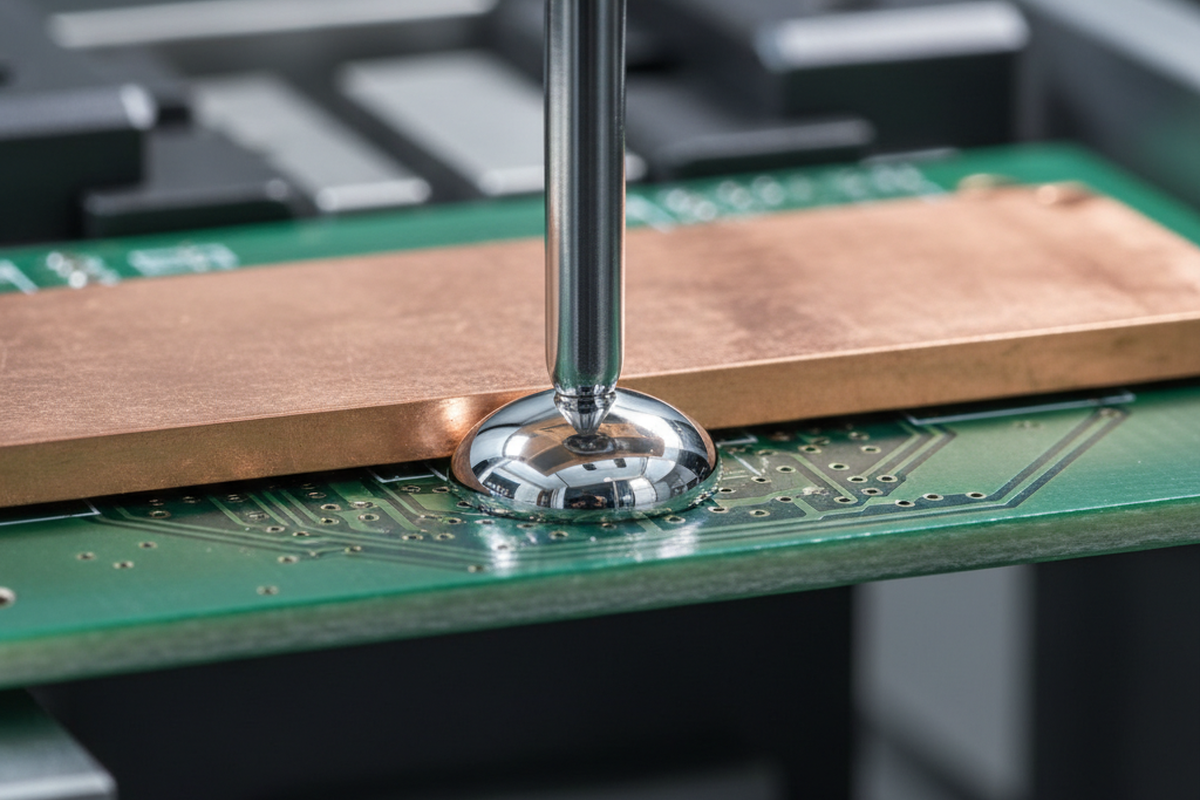

In high-reliability electronics—particularly automotive inverters and industrial power systems—the “shiny joint” is a dangerous liar. A solder joint on a 3mm copper busbar can exhibit a perfect top-side fillet, glossy wetting on the toe, and clean flux residue, yet be completely compromised internally.

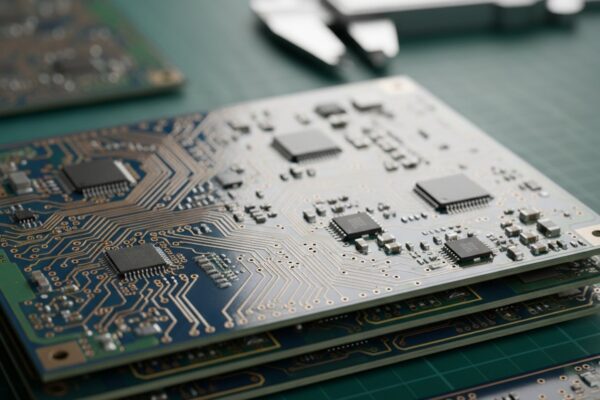

When dealing with high-current shunts and heavy busbars, standard inspection criteria like IPC-A-610 Class 3 often fail to catch the real failure mode: lack of hole fill and cold intermetallics deep inside the barrel. The heat sink effect of a heavy copper plane pulls thermal energy away from the joint faster than a standard selective nozzle can supply it. If the process isn’t tuned specifically for thermal mass, the solder freezes before it ever wets the barrel wall. This creates a mechanical connection that will eventually fail under vibration or thermal cycling. The result isn’t just a bad board; it’s a field failure in a high-voltage system.

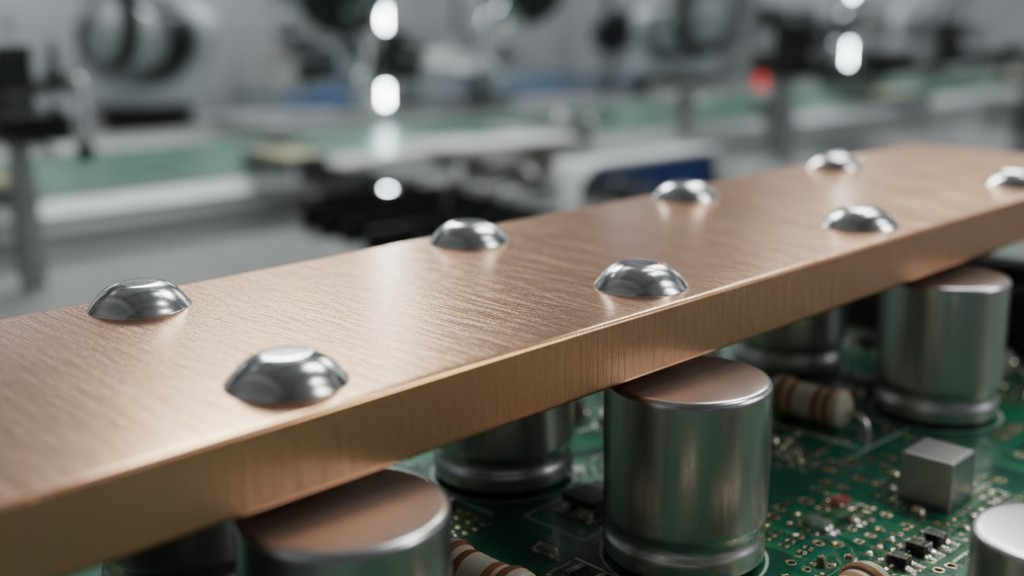

You Cannot Cheat Thermal Mass

The fundamental error in soldering heavy copper is treating the selective machine like a magic wand. It is a tool subject to the laws of thermodynamics. When a nozzle approaches a 4oz copper pour or a thick busbar lug, it is effectively trying to boil an ocean with a candle.

The copper component acts as a massive thermal reservoir. As soon as the molten solder touches the lead, the component begins to drain heat away from the liquidus front. If the component’s thermal demand exceeds the nozzle’s delivery, the solder temperature at the interface drops below the alloy’s melting point (typically 217°C for SAC305). The solder becomes slushy, wetting stops, and you are left with a cold, brittle interface that looks acceptable on the surface but has zero structural integrity.

Designers often exacerbate this by placing high-mass components without adequate thermal relief. If you are a process engineer staring at a Gerber file where a busbar connects directly to a ground plane with no spoke relief, you are looking at a defect waiting to happen. No amount of machine tuning can overcome a design that dissipates heat faster than the physics of wetting allows. In those cases, the board must go back to layout, or you must invest in expensive, custom-masked pallets to isolate the thermal load.

The Battle is Won in Preheat

Because the nozzle alone cannot overcome the thermal mass, the heavy lifting must happen before the board ever reaches the solder pot. While operators often obsess over wave height or dwell time, the critical parameter for high-mass soldering is the preheat soak.

For standard SMT components, a preheat of 100°C topside is sufficient. For a copper brick, that’s negligible. You must drive the core temperature of the component—the actual metal mass—up to at least 110°C to 120°C before the soldering cycle begins. This reduces the “thermal shock” delta the nozzle has to bridge. If the component sits at 120°C, the solder wave only needs to raise it another 100°C to achieve wetting. If the component is at 80°C, that delta is 140°C—often an unbridgeable gap within the few seconds of contact time allowed.

Achieving this requires more than just cranking up the bottom-side heaters. Standard convection preheaters often fail to penetrate thick multilayer boards quickly enough to heat a top-side busbar without scorching the FR4 on the bottom. The most robust solution typically involves top-side IR preheaters or extended soak zones that allow the heat to equilibrium through the board.

Do not guess at these temperatures. IR thermometers are useless on shiny copper busbars due to emissivity issues. The only way to validate your preheat strategy is to drill a sacrificial board, embed a K-type thermocouple directly into the barrel wall or the component body, and run a profiler. If the core temp isn’t hitting that 110°C+ mark, the process is unstable.

The Pot Temperature Trap and Dwell Time

When faced with a cold joint, the knee-jerk reaction from production management is often “Turn up the pot temperature.” This is a destructive fallacy.

Running a solder pot at 320°C or 330°C to compensate for poor preheat is a recipe for latent failure. At these temperatures, the rate of copper dissolution accelerates aggressively. You aren’t just soldering the knee of the hole; you are dissolving it. The copper pad and the barrel plating leach into the solder bulk, thinning the conductive path and contaminating your solder pot with high copper levels. This raises the liquidus point of the alloy and creates gritty, sluggish joints.

Furthermore, extreme temperatures burn off flux volatiles instantly. By the time the solder actually needs to wet the surface, the flux is charred and inactive, leading to de-wetting and voids.

Dwell time (contact time), not temperature, is the lever you need to pull. For high-mass joints, you need a longer dwell—often in the range of 3 to 6 seconds depending on nozzle diameter—to allow thermal transfer to occur. However, this is a dangerous balance. Too short, and the barrel doesn’t fill. Too long, and you risk delaminating the PCB material or leaching the pad. The window is narrow. A stable process might run a pot at 290°C with a 4-second dwell, rather than a 320°C pot with a 2-second dwell. The former preserves the metallurgy; the latter destroys it.

Chemistry and Inerting

In high-reliability selective soldering, nitrogen inerting isn’t a luxury add-on; it is a process requirement.

When you extend dwell times to heat up a heavy part, the solder wave is exposed to the atmosphere for longer periods. Without a nitrogen blanket (typically requiring 99.999% purity), the nozzle develops oxides and dross skins rapidly. A drossy nozzle delivers poor heat transfer and unpredictable wave height. You might tune the machine perfectly at 8:00 AM, but by 10:00 AM, the nozzle is clogged with oxide sludge, and the wave height has drifted by 1mm, causing open joints.

Flux selection is equally critical. For high-mass boards, the flux must survive the extended preheat cycle without losing activity. Alcohol-based, low-solids no-clean fluxes often burn off too early. If you see “gunk” or sticky residues that don’t dry, or if the flux chars before the wave hits, you may need a higher-solids formulation or a different activator package. But be careful—switching to a water-soluble flux for better activity introduces a washing requirement that many selective lines are not equipped to handle. Stick to a robust no-clean designed for high-thermal-mass profiles and ensure the drop-jet fluxer is calibrated to apply it exactly where needed, not sprayed blindly across the board.

Destructive Reality Check

Once you have tuned the preheat, dwell, and flux, how do you know it worked? You cannot trust your eyes. The only validation that matters is the cross-section.

Take your “golden board”—the one that looks perfect under the ring light—and destroy it. Pot it, polish it, and put it under a 50x microscope. You are looking for intermetallic formation (IMC) along the entire length of the barrel wall. You need to see 100% hole fill, not just 75%. You need to check for “champagne voids” near the component lead, which indicate trapped flux volatiles from a process that got too hot too fast.

If you are not regularly cross-sectioning your high-mass joints, you are flying blind. A process drift of 10°C in preheat might not change the external appearance of the joint, but it can reduce the barrel fill by 50%.

The Rework Fallacy

If a high-mass joint fails inspection, there is a strong temptation to fix it with a hand soldering iron. For heavy copper busbars and shunts, this is almost always professional negligence.

A human operator with a soldering iron cannot reliably deliver the thermal energy required to rework a high-mass joint without overheating the local area and causing pad lifting or barrel separation. The “touch-up” often does nothing more than reflow the surface solder while leaving the internal barrel cold and voided. If the selective machine cannot solder it correctly, a hand iron certainly cannot. The focus must be entirely on machine capability. If the machine misses, the board is likely scrap. Tune the process so it doesn’t miss.