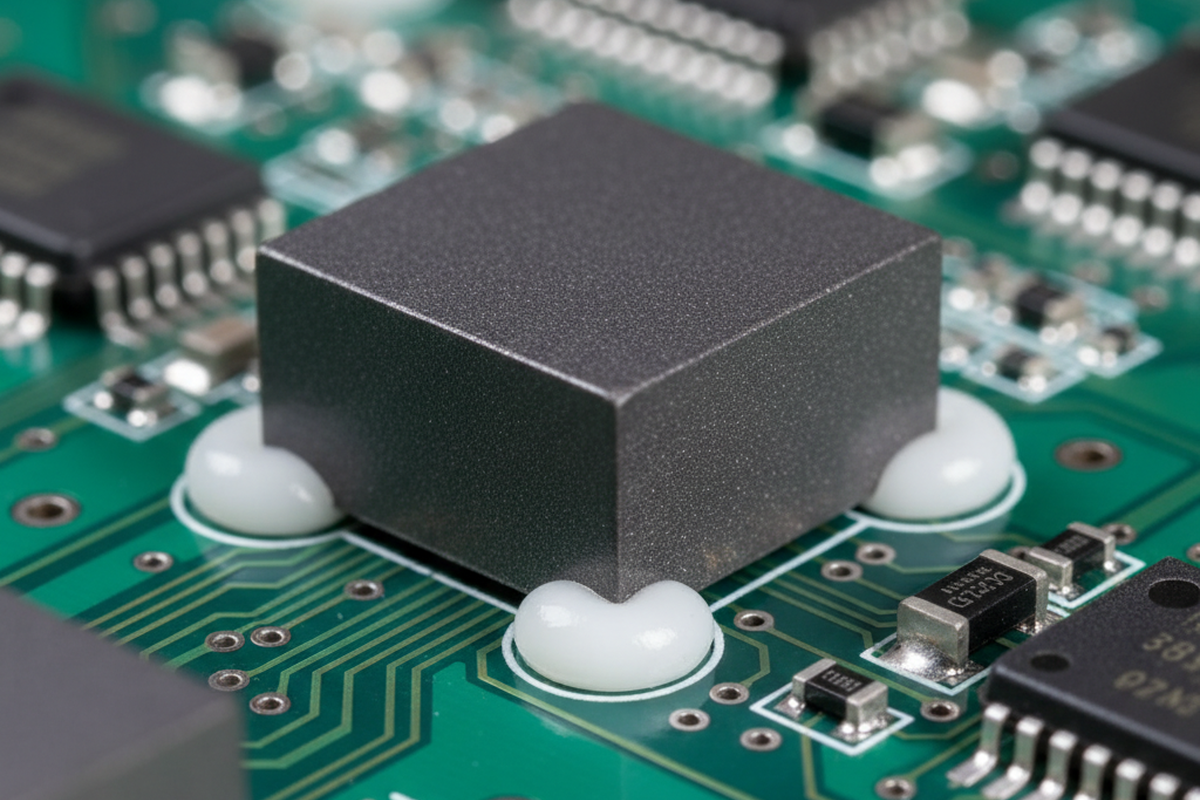

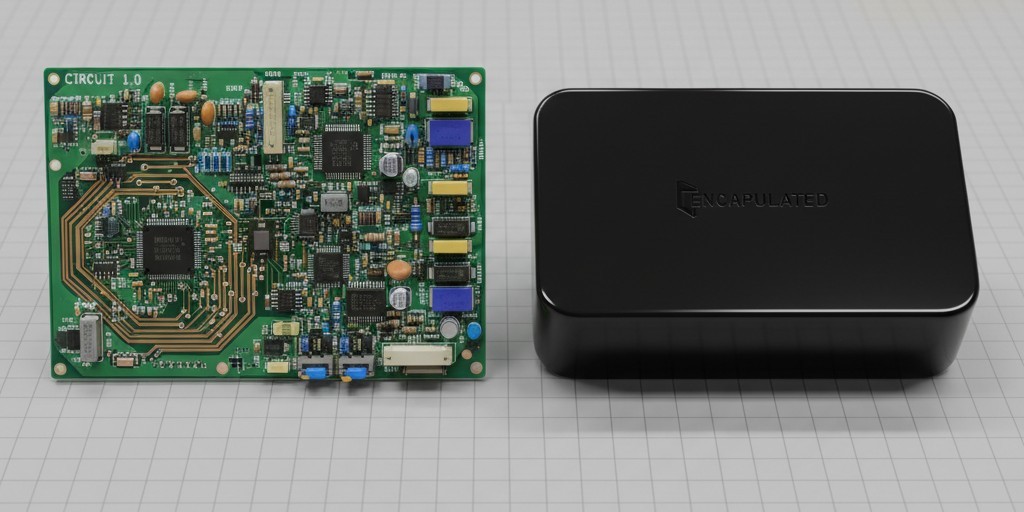

The most expensive silence in an engineering lab is the sound of a “ruggedized” board failing a thermal shock test. You’ve likely seen the aftermath: a heavy-duty controller, designed to survive inside an engine bay or an industrial HVAC unit, completely encased in a hard, black block of epoxy. The design intent was protection. The engineers wanted to stop vibration, block moisture, and pass the salt-spray validation. But when the unit comes back from the field, dead on arrival, that protection becomes a tomb. You can’t probe the rails. You can’t inspect the solder joints. You are left with a brick that holds all the secrets of its own demise, and no way to extract them without destroying the evidence.

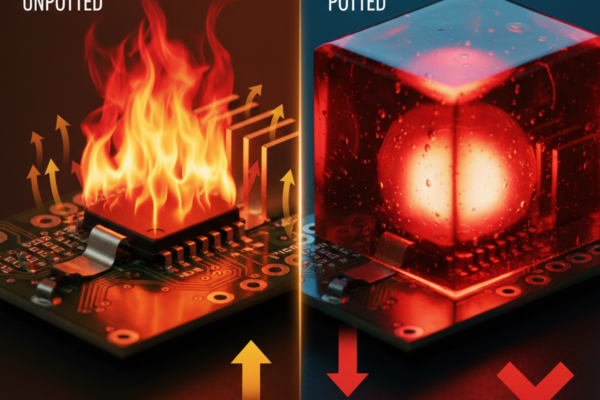

This is the central paradox of electronics ruggedization. The intuitive move—making everything solid and immovable—is often the exact wrong move for reliability. When you flood a printed circuit board (PCB) with high-modulus epoxy, you aren’t just armoring it; you’re introducing a massive new mechanical participant into the delicate thermal dance between silicon, copper, and fiberglass. True ruggedization relies less on hardness and more on compliance. The choice between full encapsulation (potting) and surgical staking is often the choice between a product you can maintain and one that will bankrupt your reputation.

The Physics of Thermal Suicide

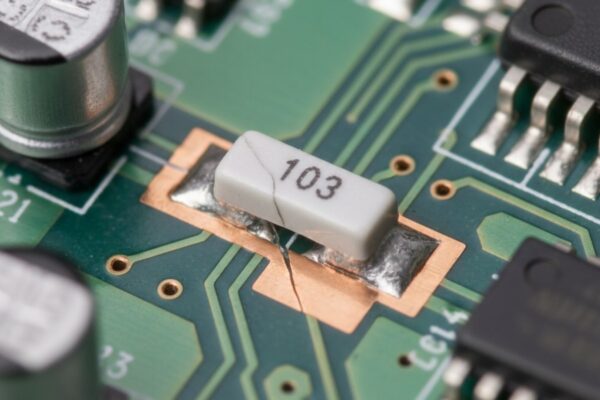

To understand why “stronger” glues often kill boards, you have to look at the numbers physics won’t let you ignore. The coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) is the silent killer here. A standard FR4 circuit board expands at a rate of roughly 14 to 17 parts per million per degree Celsius (ppm/°C). The copper traces and the fiberglass weave move together at this rate. The components soldered to that board—ceramic capacitors, silicon dies inside plastic packages—have their own rates, usually lower, ranging from 6 to 20 ppm/°C. The solder joints absorb this slight mismatch, flexing microscopically as the device heats up and cools down.

Now, introduce a generic potting compound. Most hard epoxies used for “protection” have a CTE anywhere from 50 to 80 ppm/°C. This is where the disaster starts. As the device heats up—whether from internal power dissipation or an ambient shift from -40°C to +85°C—that large block of epoxy expands three to four times faster than the board it encapsulates. At that point, it stops acting as a protective coating and becomes a hydraulic press. The epoxy grips the components and pulls them. Since the epoxy is massive and stiff, and the solder balls on a BGA (Ball Grid Array) are small and soft, the epoxy wins. It shears the solder balls right off the pads, or worse, rips the copper pads out of the PCB laminate entirely (pad cratering).

Don’t confuse this mechanical aggression with the benign nature of conformal coating. Engineers often conflate the two, asking if a spray coating is “enough” protection. Conformal coatings—acrylics, urethanes, thin silicones—are microns thick. They exist to stop dendrite growth and corrosion from humidity. They don’t have the mass to exert force on components. Potting and thick staking are structural; they transfer force. If you use a material that expands like a balloon inside a rigid steel pipe, something has to break. Usually, it’s the electrical connection you were trying to save.

Stiffness is the Enemy

Since you can rarely match the CTE perfectly—datasheet values for cured polymers are notoriously optimistic and vary by batch—you must change the variable you can control: stiffness. In materials science, this is Young’s Modulus. It’s the difference between being hit by a pillow and being hit by a brick. Both might weigh the same, but the energy transfer is different.

High-modulus materials, like many rigid epoxies or cyanoacrylates (super glues), transfer stress directly to the weakest link. If you glue a heavy inductor down with a rigid adhesive and the board vibrates, the glue won’t flex. The energy passes through the glue and concentrates on the copper foil of the PCB. The result is often a component that is still perfectly glued to a patch of ripped-up fiberglass, disconnected from the circuit.

The alternative is low-modulus materials, typically silicones or modified urethanes. A silicone RTV (Room Temperature Vulcanizing) rubber might have a massive CTE—sometimes over 200 ppm/°C—but it is so soft (low modulus) that it doesn’t matter. When it expands, it squishes rather than pulls. It acts as a shock absorber instead of a stress transmitter. There is a reason you see silicone used in high-vibration automotive environments despite its chemical headaches: it complies. It forgives the movement of the board.

Surgical Staking: The Middle Path

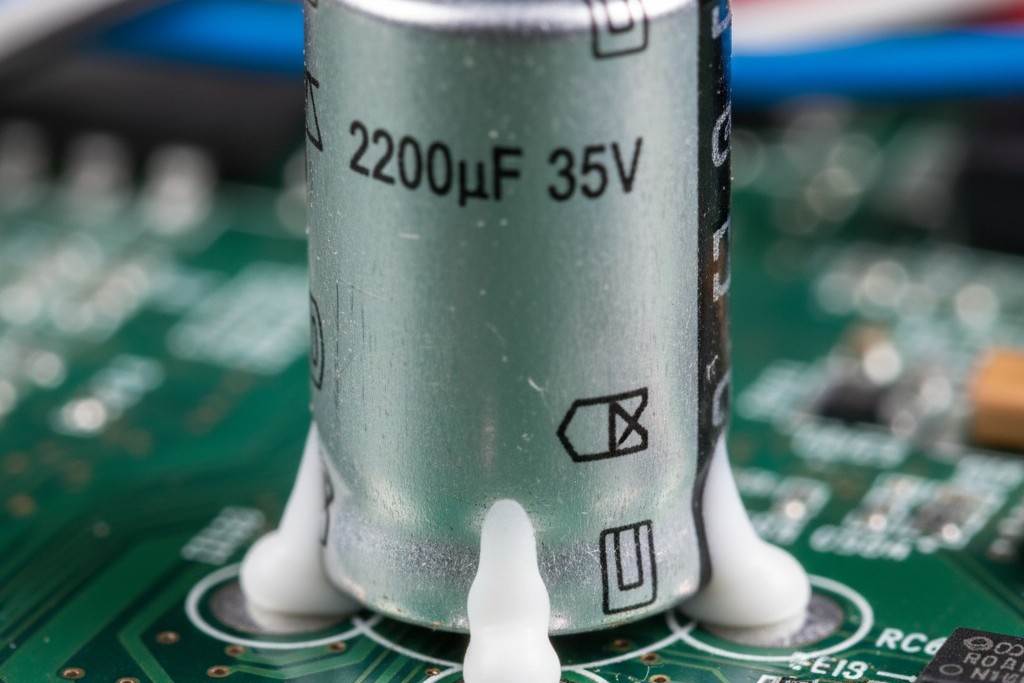

The most reliable boards in the field usually avoid full encapsulation unless absolutely necessary for high-voltage arc suppression or deep-sea pressure. Instead, they rely on surgical staking. This is the practice of securing only the components that actually need it—tall electrolytic capacitors, heavy inductors, and connectors—while leaving the board itself free to breathe.

The goal is to stop mechanical fatigue without inducing thermal fatigue. You don’t need to drown a component to save it. A common mistake, often imported from the handheld/mobile device world, is the urge to “underfill” everything. In a phone, underfill protects against a single catastrophic drop event. In industrial gear, underfill often creates a thermal expansion nightmare during years of daily temperature cycling.

The better approach for heavy components is “corner bonding” or “fillet staking.” You apply a compliant adhesive to the corners or the base of the component, creating a wide footprint that resists vibration. This increases the mechanical leverage of the mount without locking the component body into a rigid thermal cage. You are essentially adding shock absorbers to the heavy items. The solder joints carry the electrical signal; the staking carries the mechanical load. They should be separate duties.

The Rework Reality

Ultimately, if you cannot remove the ruggedization, you do not actually own the reliability data of your product. When a potted module fails, and you can’t dissolve the potting without using harsh chemicals like Dynasolve that also eat the soldermask and labels, you are flying blind. You cannot perform a root cause analysis. Was it a bad solder joint? A counterfeit capacitor? A cracked trace? You’ll never know. You will just throw it in the scrap bin and hope the next batch is better.

For a ten-dollar sensor, maybe that disposable economics works. But for a critical controller, “No Fault Found” returns are a bleed on your engineering resources. A staking material that can be peeled off or cut through with a hot knife allows you to replace a component, verify the failure, and actually fix the process. Repairability isn’t just fixing a single unit—it’s securing the access to learn why it broke in the first place. If you entomb your mistakes in epoxy, you are doomed to repeat them.