The gap between a perfect Bill of Materials (BOM) and the physical reality of a cardboard box arriving at the intake bay is often the most expensive space in manufacturing. In a digital file, every component exists in exact quantities, perfectly aligned with its footprint, ready for assembly. In the receiving dock, however, that same project often arrives as a “kit” that looks less like a production run and more like a hastily packed suitcase. We have seen fifty-thousand-dollar prototype runs stall because a handful of 0402 resistors were tossed loose into a Ziploc sandwich bag—unlabeled, static-charged, and impossible to feed into automation.

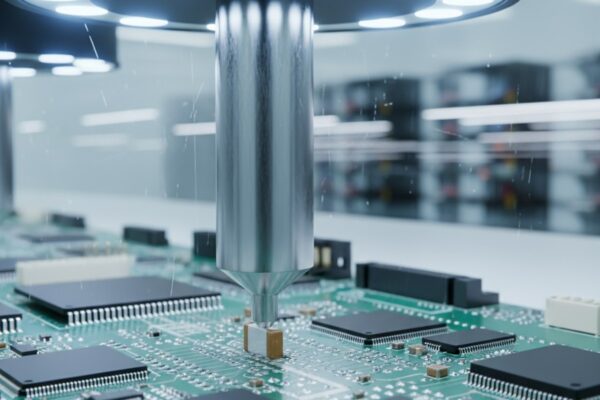

This is why the audit exists. We don’t do it to generate paperwork or delay the project; we do it to build a physical firewall. Once a kit crosses from the receiving dock into the production cage, it is treated as “machine-ready.” If that assumption proves false during the run, the consequences are immediate and financial. A pick-and-place machine running at 20,000 components per hour won’t pause to ask clarifying questions about a handwritten label. It simply stops. The audit is the only mechanism available to prevent that silence.

The Lie of the Spreadsheet

There is a pervasive belief that if a spreadsheet says there are 5,000 capacitors on a reel, then there are 5,000 capacitors on that reel. This is rarely true, especially when dealing with open stock or parts sourced from the gray market. Spreadsheets make claims; scales verify them. When a consigned kit arrives, the first step isn’t reading the packing slip—it’s interrogating the physical inventory.

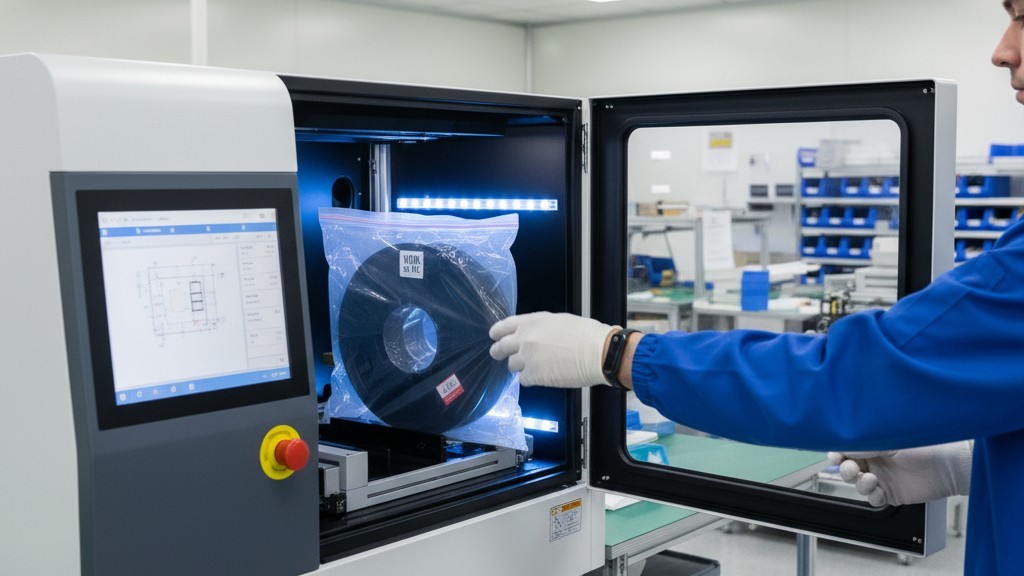

We don’t count components by hand. Human counting is slow and prone to “fatigue blindness,” where the brain assumes the count is correct just to finish the task. Instead, we use precision counting scales and X-ray counters. An X-ray counter can scan a sealed moisture-barrier bag and identify the exact number of chips inside without ever breaking the seal. This is critical for high-value FPGAs or moisture-sensitive devices (MSDs) where opening the bag starts a clock you don’t want ticking until the last possible moment.

This rigorous counting often triggers frustration for teams debating between Full Turnkey services and Consigned Kits. If you buy the parts yourself to save money, you assume the risk of that inventory’s accuracy. If you buy a “partial reel” from a broker that claims to have 500 chips, and the X-ray reveals 420, that shortage is your problem to solve. In a Turnkey model, the factory absorbs that variance. In a Consigned model, the variance stops your build.

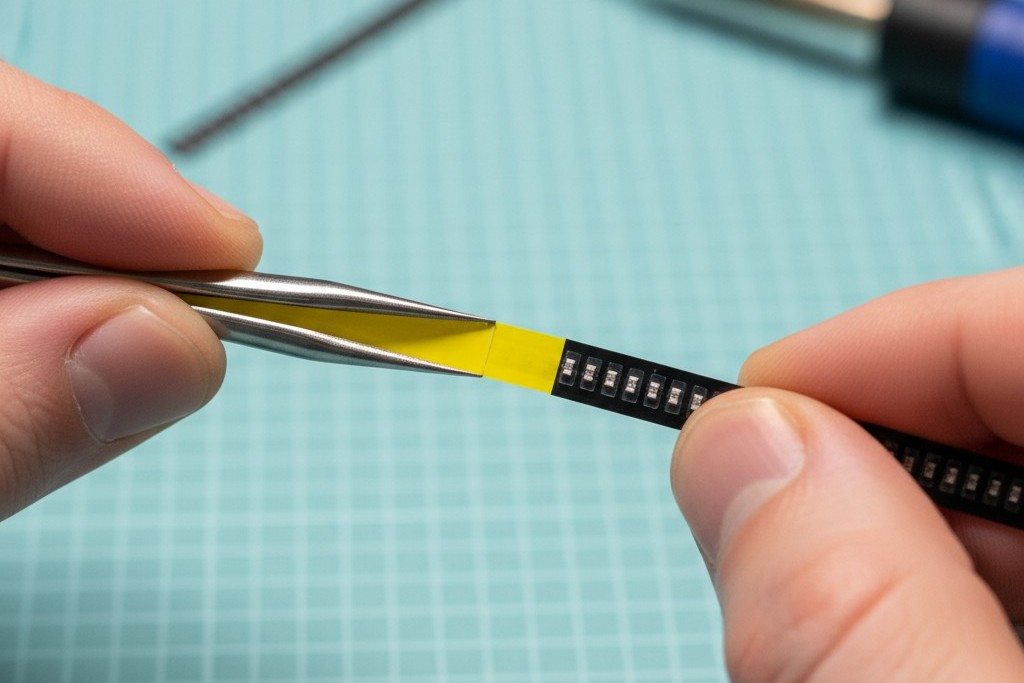

The most dangerous phrase in an audit is “close enough.” A client might send a strip of cut tape that looks like it has about 50 parts for a 40-board run. To the naked eye, it looks sufficient. To the machine, it is a guaranteed failure. We often have to challenge the “Trust My Count” argument. You may have counted them yesterday, but if the leader tape was trimmed or a few parts fell out during packing, the machine will run dry before the final board is populated.

The Physics of Attrition

The single most contentious part of any kit audit is attrition—the “extra” parts required to build the job. Clients hate attrition. It feels like buying waste. Why do you need 115 parts to build 100 boards?

It comes down to the mechanics of the SMT feeder. Feeders aren’t magic; they are mechanical systems that require tension and traction to advance the tape. To load a reel into a feeder, we have to peel back the cover tape and thread the carrier tape into the drive sprocket. This process consumes a length of tape—the “leader”—before the pick-point is even reached. Depending on the machine platform, this leader can be anywhere from 6 to 12 inches long. If you send exactly 100 parts on a continuous strip for a 100-board run, the first 15 to 20 parts are sacrificed just to load the feeder. The machine cannot pick them because they are physically located inside the threading mechanism.

This confusion often stems from a misunderstanding of how cut tape works. If you send a 2-inch strip of tape, there is no physical way to load it into an automatic feeder. We have to manually splice on a leader extension, a delicate operation that adds labor time and risk. If the tape is too short even for splicing, we are forced to hand-place the components.

Some engineers will argue, “Just hand-place it, it’s only 50 boards.” While a human can place a part, they cannot do it with the consistency or speed of a machine. Hand placement breaks the thermal profile consistency, increases the risk of part misalignment, and turns a 2-hour automated job into a 2-day manual slog. For a 0402 passive or a fine-pitch IC, hand placement isn’t a viable “agile” strategy. It is an expensive rescue operation.

The math of attrition isn’t arbitrary, though it varies by machine type (a MyData Agilis feeder wastes less than a traditional Juki or Panasonic mechanical feeder). Generally, for passive components (resistors, caps), we require a percentage overage plus a fixed leader count. For expensive ICs, the overage requirement drops, but the leader requirement remains. If you send exact counts, you are effectively scheduling a shortage.

Package Integrity and Moisture

Beyond the count, the audit verifies that the parts can actually survive the assembly process. This is where the difference between a “part” and a “manufacturing-ready component” becomes painful. We frequently see kits containing Moisture Sensitivity Level (MSL) 3 or 4 components—like BGAs or QFNs—that have been sitting loose in a desk drawer for months.

When these parts absorb atmospheric moisture, they become ticking time bombs. If we put them directly into a reflow oven at 245°C, the trapped moisture turns to steam, expands, and cracks the package from the inside—a phenomenon known as “popcorning.” The audit checks the humidity indicator cards in the bags. If the card indicates exposure, or if the parts arrive in generic packaging without desiccant, we must bake them for hours or days to drive the moisture out. This adds time to the schedule that no one accounted for.

We also verify the physical footprint against the board layout. A common “silent killer” occurs when a designer swaps a part in the BOM—say, changing a transistor from a SOT-23 to a smaller SOT-323—but forgets to update the PCB layout file. The parts arrive, they are the correct electrical value, but they physically won’t fit the solder pads. If we catch this during the audit, we can scramble for an alternate. If we catch it on the line, the machine crashes, and the board potentially requires a layout spin.

This brings up the issue of alternates. Often, a client will email saying, “If you can’t find the Murata cap, the TDK one is fine.” That is helpful, but if that approval lives in an email chain and not in the official BOM or the kit data, the audit will flag the TDK part as “Wrong MPN” (Manufacturer Part Number). The physical kit must match the documentation exactly. We cannot guess which deviations you have mentally approved.

The Hold Protocol

When the audit uncovers a shortage—whether it’s a missing reel, a bag of crushed parts, or a discrepancy in attrition—the job goes on “Hold.” This status in the ERP system locks the job out of the scheduling queue. It is the moment most dreaded by project managers, but it is necessary.

We recently handled a kit that arrived two days before a critical launch deadline. The audit flagged a shortage of fifteen line items. The client was furious, demanding we “start with what we have.” We refused. Starting a board with known shortages means pulling it off the line halfway through, storing it (which invites dust and handling damage), and then breaking into the schedule again days later to finish it. The setup and teardown times alone destroy the efficiency of the run. We waited five days for the missing parts to arrive from DigiKey. The client screamed about the delay, but they received 100% completed, functional boards.

If we had run the job partial, they would have received half-built skeletons requiring hand-soldering rework that would have taken weeks to verify. The audit is strict because the alternative is a manufacturing disaster. When we weigh the reel, check the seal, and reject the cut tape, we aren’t trying to be difficult. We are ensuring that when the start button is pressed, the line doesn’t stop until your product is done.