The global supply chain isn’t a clean, well-lit warehouse; it is a fog of war. When authorized distributors like Digi-Key, Mouser, or Arrow run dry, procurement teams are forced into the “gray zone” of independent brokers. Here, the rules of engagement change. In the authorized channel, a part number is a guarantee. In the broker market, it’s merely a suggestion.

The risk isn’t just that the part won’t work. The real danger is that it will work just enough to pass a basic functional test, only to fail six months later in a medical ventilator or an avionics bay. Consequently, incoming inspection isn’t about verification—it’s about disqualification. You must assume every reel, tray, and cut-tape strip is guilty until it survives a gauntlet of forensic analysis.

This applies even to parts supplied by the client. There is a dangerous misconception with “consignment” or customer-furnished material: because the client bought it, it must be safe. False. Clients are often more desperate and less experienced than professional buyers. If a client hands you a bag of chips they found on a forum, treat those parts with the same suspicion as a random lot from Shenzhen.

The Paperwork Hallucination

Documentation is the first line of defense, but it is also the most porous. A Certificate of Compliance (CoC) from a broker is often legally and technically worthless. Unless that piece of paper traces an unbroken chain of custody back to the Original Component Manufacturer (OCM), it is just a photocopy of a promise.

Do not read the paperwork; autopsy it. Counterfeiters excel at replicating logos but fail at data consistency. Check the font on the label. Manufacturers like Texas Instruments or Analog Devices use specific, proprietary fonts and spacing for their lot codes. If the font looks like standard Arial or Times New Roman, or if the kerning is uneven, the label is a fabrication.

Scan the barcode. The 2D DataMatrix or 1D barcode must match the human-readable text exactly. We often find “lazy” counterfeits where the label reads “Lot 2245” but the scanned barcode data reveals “Lot 1809″—the counterfeiter simply copied a barcode from an older label. Cross-reference the date codes, too. If the label claims the part was made in 2022, but the manufacturer issued an End-of-Life (EOL) notice for that package type in 2019, the part is a ghost. It shouldn’t exist.

Surface Tension: Visual & Sensory Inspection

Before putting a part under the microscope, use your nose. Open the moisture barrier bag (MBB) and smell the contents. Freshly manufactured electronics have a neutral, slightly plastic scent. Parts that have been “washed”—stripped from e-waste boards and cleaned with industrial solvents—often carry a sharp chemical sting or the smell of stale ozone and burning.

Check the Humidity Indicator Card (HIC). If the 10% dot is pink, the desiccant is dead. This is a common failure in the broker market that leads to Moisture Sensitivity Level (MSL) violations. If you reflow these “wet” parts without baking them according to J-STD-033, the moisture inside the package expands into steam and cracks the die—the “popcorn” effect.

Under a high-power digital microscope (like a Keyence VHX or similar system), the component surface tells the real story. Look for “witness marks.” Authentic parts leave the factory with pristine leads. Pulled parts—those desoldered from old boards—will show microscopic scratches on the leads from the original socket or insertion machine. Also, watch for re-tinning. If the solder plating looks uneven, thick, or bubbly, it has likely been dipped by hand to cover old oxidation.

Then there is the issue of “New Old Stock.” Buyers often ask if a part with a date code from five years ago is safe. The answer: maybe. The silicon inside doesn’t rot, but the termination plating does. Oxidation on the leads can make the part impossible to solder, resulting in cold joints. If the date code is older than 24 months, solderability testing is mandatory.

Solvent and Fury: The Remarking Test

Visual inspection is useless against “blacktopping,” the most common modern counterfeiting technique. Fraudsters take a cheap, low-spec chip (or a totally different part with the same pin count), sand off the original markings, and coat the top with a black epoxy resin. They then laser-etch a new, expensive part number onto that fresh surface. To the naked eye, and even under a standard scope, it looks perfect.

You have to destroy the surface to see the truth.

Solvent resistance testing exposes this lie. The standard test uses a mixture containing acetone or a specialized agent like Dynasolve 750. Dip a cotton swab in the solvent and rub the top of the component with pressure. Authentic epoxy mold compound is cured under high heat and pressure; it is impervious to these solvents.

If the top surface starts to dissolve, gets sticky, or wipes away to reveal a different texture, the part is blacktopped. We have seen instances where a “Consumer Grade” temperature rating wipes off to reveal an “Industrial Grade” part underneath—or vice versa. In one case involving STM32 microcontrollers, the swab turned black instantly, revealing a blank surface. The laser marking was floating on a layer of paint. If that chip had gone into an automotive dashboard, it would have failed the first time the car sat in the sun.

Deep Tissue: X-Ray Verification

Chemistry catches surface lies, but only X-rays reveal structural deceit. Counterfeiters can fake a label and blacktop a package, but they cannot change the silicon die inside.

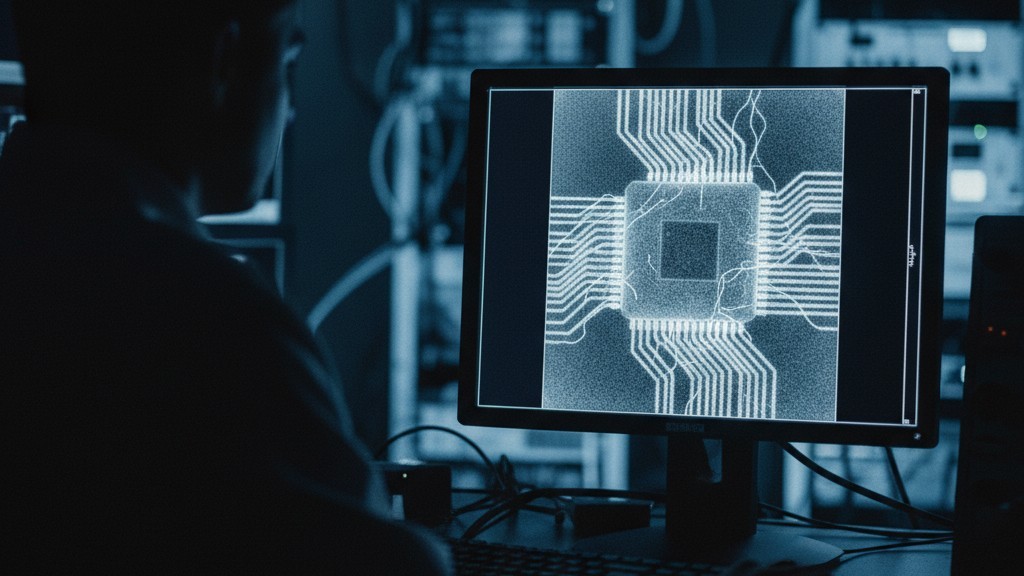

This verification relies on the “Golden Sample” method. You must retrieve a known authentic part—perhaps from an old board or a previous authorized buy—and X-ray it side-by-side with the suspect part. Compare the lead frame geometry and the bond wires.

Different manufacturers use different wire bonding patterns. A Xilinx FPGA made in 2020 will not have the same internal layout as a clone made in a different fab. Check the die size. If the suspect part’s die is 20% smaller than the Golden Sample, it is likely a lower-capacity chip remarked to look like the expensive version.

Some argue that functional testing substitutes for this. “Just plug it in and see if it boots,” they say. This is a dangerous fallacy. A counterfeit or damaged part might pass a functional test today. But if the bond wires are corroded, or if the die was damaged by ESD during the “pulling” process, that part is a walking wounded soldier. It will fail, but only after you have soldered it to a $5,000 board and shipped it to the customer. X-ray (specifically 2D real-time or 3D CT) is the only non-destructive way to verify wire integrity. Note that interpreting X-ray images is an art; bond wires can look broken at certain angles due to “shadowing,” so operator expertise is critical to avoid false positives.

The “Trojan Horse” Return

The suspicion applied to incoming broker parts must also apply to RMAs (Return Merchandise Authorizations). When a client returns a board claiming a defect, do not assume they are correct. Clients lie, often unintentionally, to cover up handling damage.

We often see boards returned for “reflow defects” where, under the microscope, the leads of a QFP package are bent upwards. Reflow ovens do not bend leads upwards; gravity pulls them down. Upward bending indicates mechanical stress—someone dropped the board or pried it out of a fixture. By treating returns with the same forensic rigor as incoming parts, you protect the manufacturing team from accepting liability for abuse.

The Cost of Certainty

Testing is expensive. A full suite—visual, solvent, X-ray, decapsulation, solderability—can cost thousands of dollars and take days. Procurement teams will complain about the cost. They will complain about the lead time.

But the math is simple. A reel of fake capacitors costs far more than the $500 invoice price. It costs you the 5,000 boards you built with them, the technician hours to rework them, the line-down penalties from the client, and the reputational crater left when your hardware fails in the field. In the high-mix, high-reliability world, we don’t inspect to add value. We inspect to prevent catastrophe.