Picture a MedTech startup in 2018. They are three weeks away from an FDA submission deadline, holding a 2,000-unit production run that absolutely must work. To prove their seriousness to investors, they ordered the “Gold Standard” of manufacturing test: a custom In-Circuit Test (ICT) fixture. It’s a beautiful piece of machined aluminum, drilled with hundreds of holes for spring-loaded probes, designed to verify every single resistor and capacitor on the board. It cost $35,000 and took eight weeks to machine.

But when the fixture finally arrives on the loading dock, there is a problem. The board layout had to change slightly in “Rev B” to fix a thermal issue. The mounting holes moved by three millimeters.

The fixture is now a thirty-five thousand dollar paperweight. It cannot be modified; it must be scrapped. The startup has burned $35k and two months of runway, and they still haven’t tested a single board.

This scenario plays out constantly in hardware development. Engineers are trained to seek “100% coverage” and often default to the heavy-duty tools used by giants like Apple or Dell. But physics is easy compared to economics. When you are building 500, 2,000, or even 5,000 units, the math of traditional “Big Iron” testing breaks down. You need a strategy that prioritizes flexibility over speed, and functional reality over structural perfection.

Why the “Gold Standard” Fails You

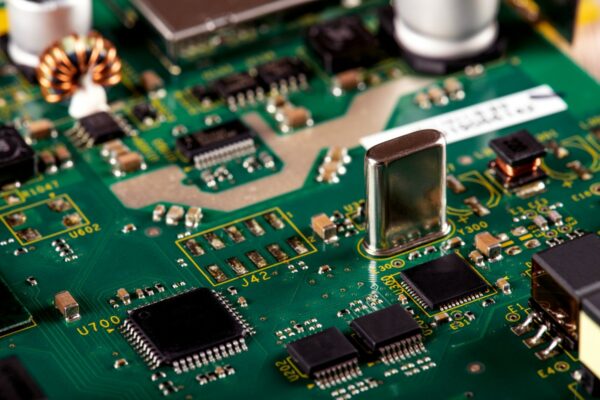

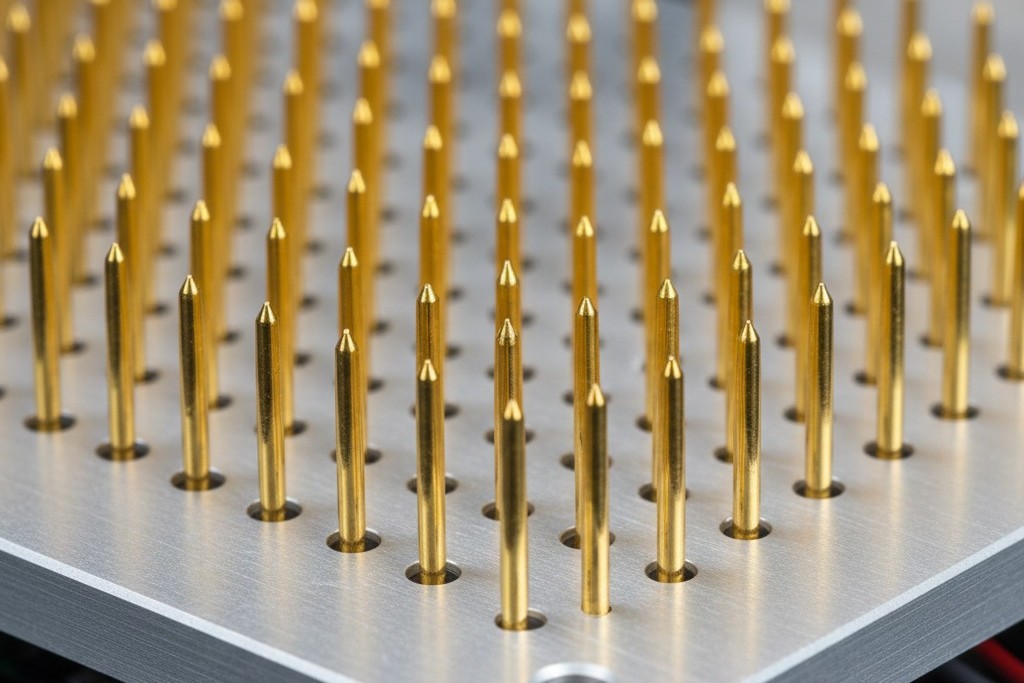

In high-volume manufacturing—think 100,000 units a month—ICT is king. A “Bed of Nails” fixture clamps down on the board, and in six seconds, it tells you exactly which 0402 resistor is the wrong value. It is fast, precise, and incredibly expensive. The Non-Recurring Engineering (NRE) cost for the fixture, programming, and debug time can easily hit $15,000 to $50,000. If you are building a million units, that cost amortizes to pennies per board. If you are building 1,000 units, you are paying a $15 tax on every single device just for the privilege of testing it.

And this is where many teams get confused about “Burn-In” versus “Test.” You might be tempted to ask for extensive burn-in racks to catch early failures, thinking that replaces the need for a fixture. It doesn’t. Burn-in is a stress test to catch infant mortality—components failing after 48 hours of heat. It tells you if the board lasts. It doesn’t tell you if it was built right in the first place. You cannot burn-in a board that has a solder bridge on the power rail; you’ll just burn a hole in the PCB. You still need a way to verify the build quality without buying the aluminum beast.

In low-volume runs, cycle time is irrelevant. Fixed cost and rigidity are the real enemies. A Bed of Nails requires a “locked” design. If you move a test point, the fixture dies. In the chaotic world of New Product Introduction (NPI), where Rev C follows Rev B within a month, locking your design for a fixture is a strategic error. You need a test method that can adapt as fast as your layout designer can route traces.

The Flying Probe: Trading Time for Money

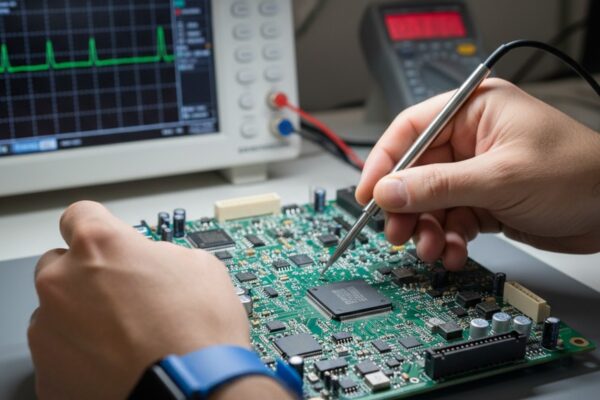

The immediate alternative to the fixed fixture is the Flying Probe. Imagine a large machine where, instead of a simultaneous clamp of hundreds of nails, four to eight robotic arms whir around the board, darting in to touch test points one by one. It looks like a sci-fi surgery robot.

The magic here is that there is no fixture. You load the CAD data (the ODB++ or Gerber files) into the machine, tell it where the parts are, and it figures out how to test them. If you move a resistor in the next revision, you just upload a new file. The NRE drops from $20,000 to perhaps $2,000 for setup. The trade-off, of course, is time. While a Bed of Nails tests a board in seconds, a Flying Probe might take three to six minutes per board depending on component density.

Do the math. If you are building 1,000 units, an extra four minutes per board is roughly 66 hours of machine time. That is negligible compared to the weeks you would wait for a fixture to be machined. However, Flying Probe has a distinct limitation: it is primarily a structural test. It checks if the parts are there and if the solder joints are connected. It generally cannot power up the board and talk to the firmware because it can’t hold all the power and data pins connected simultaneously. It tells you the body is assembled, but not if the brain is alive.

Functional Test: Does It Actually Boot?

This forces a critical realization for low-volume hardware: Functional Test (FCT) coverage is often more valuable than structural coverage. You can have a board where every solder joint is perfect, every resistor measures 10k ohms, and the board still fails to work because the crystal oscillator is the wrong frequency or the flash memory is timing out.

Consider the “Ghost in the Flux” incident. A batch of boards was failing intermittently in the field, causing havoc. The structural tests passed every single unit. It turned out the contract manufacturer was using a specific “no-clean” flux that, under high humidity (like 90% in a non-climate-controlled warehouse), became slightly conductive. No amount of measuring resistance would catch that. Only a functional stress test—powering it up and running it—caught the failure.

You have to separate “Manufacturing Test” from “Certification.” Clients often panic and ask if the functional test covers FCC or UL compliance. It doesn’t. Compliance is a legal check done once by a specialized lab. Manufacturing functional test is an existential check done on every unit: Does it boot? Can it talk? Are the rails stable? For a 2,000-unit run, knowing your device boots and communicates over USB is worth infinitely more than knowing R204 is exactly within 1% tolerance.

Strategy: Firmware is Free, Aluminum is Expensive

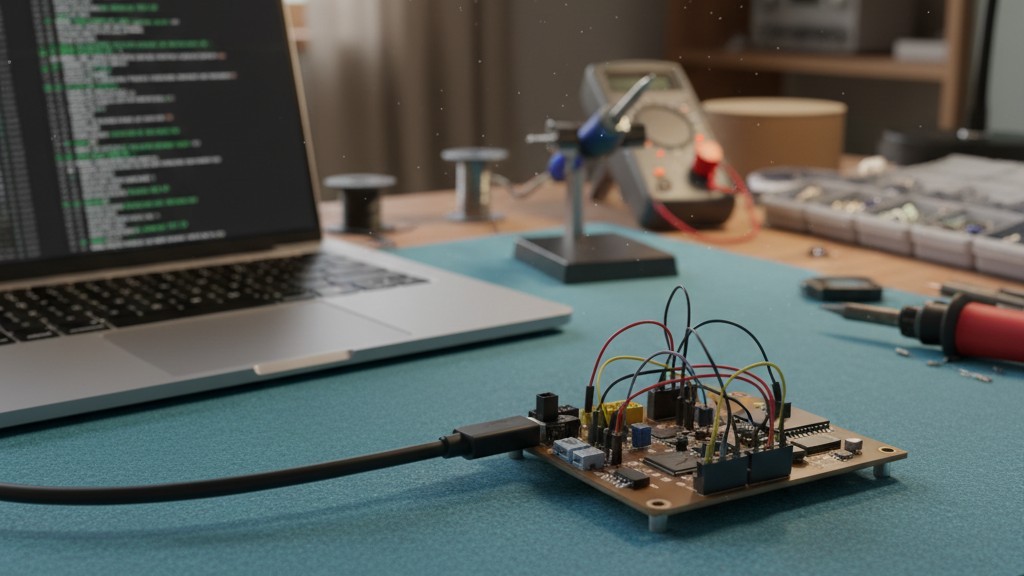

The smart strategy for low-volume production is Co-Design. You replace the expensive aluminum fixture with free firmware. This is not something you can bolt on after the design is finished; it must be in the schematic.

You need to design a “Factory Mode” into your device. This is a special firmware state triggered by a physical action—pulling a GPIO pin low, holding a button during boot, or receiving a specific command over UART. When the board wakes up in this mode, it shouldn’t wait for a user; it should immediately run a self-test. It checks its own internal rails, pings the accelerometer to see if it responds, tries to write and read from the EEPROM, and then reports the result.

Physically, this is simple. You don’t need a $50k rack. You need a USB cable, a simple pogo-pin clamp for the debug header (Tag-Connect is a lifesaver here), and a laptop running a Python script. If you want to be fancy, use a Raspberry Pi. The operator plugs it in, the script listens for the “I am alive” message from the firmware, and logs the serial number to a Google Sheet. Total hardware cost: $200. Total NRE: a week of your firmware engineer’s time.

But you have to be brutal about the “Physicality” of this. If you hide the USB port behind a bracket, or if the debug header is buried under a battery, you have broken the process. I’m not going to teach you how to write the Python code—that’s standard homework—but I will tell you that if you don’t expose those test points on the edge of the board, you are choosing to spend money on X-rays later.

The Human in the Loop

There is a persistent fantasy among tech-optimist founders of “Lights Out Manufacturing”—a factory where robots do everything. In reality, for a 3,000-unit run, a human operator is always cheaper than a robot arm. Your test strategy must be designed for a human who is tired, bored, and has been plugging in cables for six hours.

If your test requires the operator to manually plug in twelve different connectors, you are guaranteeing failure. I’ve seen lines where operators, exhausted by the repetition, started forcing DB9 connectors in at an angle, damaging the board-side headers. By board #50, the “test” was actually destroying the product.

Design for the human hand. Use keyed connectors that can’t be plugged in backwards. Use a barcode scanner so they don’t have to type serial numbers. And most importantly, minimize the physical actions required to start the test. Ideally, they plug in one cable, and the test starts automatically. If they have to click “Start” on a screen, they will eventually forget to click it or click it twice.

The “Cost of Escape” Verdict

This is a cold calculation of risk. We call it the “Cost of Escape.” If you spend $50,000 on a full ICT fixture, you might catch 99.9% of defects. If you spend $2,000 on a smart functional test setup, you might catch 99.0%.

Is that 0.9% difference worth $48,000? If you are building pacemakers, yes. If you are building consumer IoT gadgets where a field failure just means mailing a replacement unit for $50, then absolutely not. Don’t let the pursuit of theoretical perfection bankrupt your production run. Design the test into the code, respect the human operator, and ship the hardware.