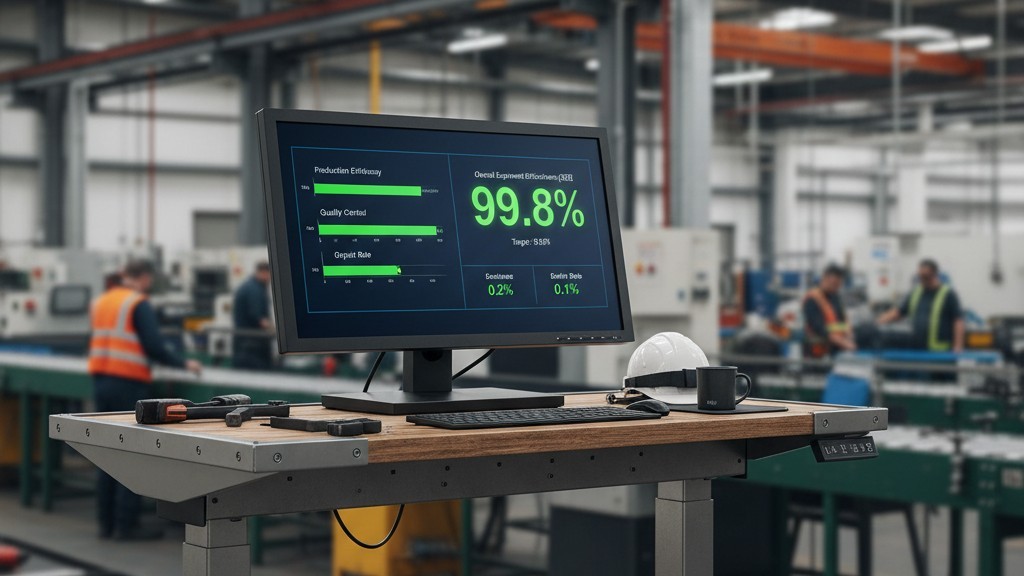

You’re looking at a yield chart that is almost entirely green. The In-Circuit Test (ICT) shows 99.8% pass rates. The functional testers at the end of the line are singing. The product is packed, shipped, and launched.

Then, three weeks later, the phone rings.

The field returns aren’t coming in as dead units, but as “drifters.” Microphones with a noise floor that has inexplicably risen. Pressure sensors reporting altitude changes while sitting on a desk. Accelerometers that have developed a permanent offset. When you re-test them on the bench, they might even pass again for a moment, or show intermittent faults that vanish when you press on the package. The factory swears the process was perfect. The reflow profiles look like textbook examples of thermal management.

This is the “Walking Wounded” scenario. You’re dealing with a failure mode invisible to electrical testing at the factory exit but fatal to the product’s longevity. This isn’t a soldering defect or a bad batch of silicon. It is almost certainly a moisture-induced delamination event that occurred weeks ago, inside the reflow oven, because of a process violation that no logbook recorded.

The Physics of the Slow Death

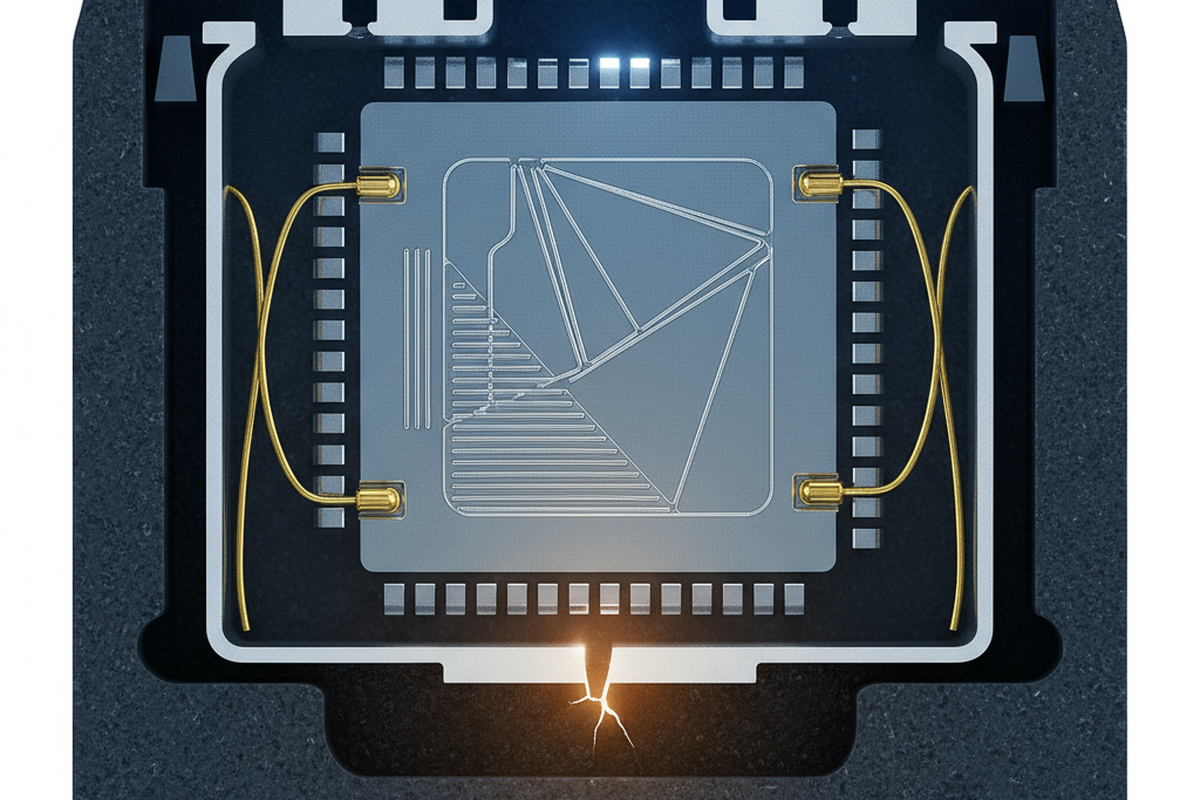

To understand why these parts are dying on a delay, you have to stop thinking about them like standard Integrated Circuits (ICs). If you mistreat a standard SOIC or QFP package with moisture, it “popcorns.” The moisture turns to steam, the pressure exceeds the plastic’s strength, and the package cracks audibly. You see the crack, you scrap the board. It’s ugly, but it’s honest.

MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) are different. They are complex mechanical structures—tiny diving boards, membranes, and combs—housed inside a cavity. When moisture penetrates a MEMS package, it settles into the interface between the molding compound and the substrate, or the die attach paddle.

When that part hits the reflow oven, the temperature spikes to 260°C. That trapped moisture flashes into superheated steam. But unlike a solid chunk of plastic, the MEMS package often has internal voids and diverse material interfaces. Instead of cracking the outside of the package, the steam pressure finds the path of least resistance: it delaminates the internal layers. It separates the die from its attach pad or lifts the molding compound just microns off the lead frame.

The part doesn’t explode. It just takes a deep breath and expands.

Crucially, the electrical connections—usually gold wire bonds—often stretch just enough to maintain contact. The unit cools down, the gap closes slightly, and it passes electrical continuity. It walks right through your ICT.

But the damage is done. You now have a microscopic delamination gap. Over the next few weeks, as the device cycles through daily temperature changes or humidity in the user’s environment, that gap breathes. It pumps in contaminants. If you’re using a no-clean process, flux residues that were supposed to be harmless on the surface can be sucked into these new crevices. Once inside, they mix with moisture to form a conductive electrolyte.

Slowly, corrosion eats away at the bond pad or the delicate MEMS structure itself. Or, the mechanical stress of the delaminated die causes the MEMS membrane to relax, shifting its zero-point. This is why you see “sensor drift” weeks later. The part isn’t broken; it’s unmoored.

The Crime Scene: It’s Not the Oven

When these failures hit, the first instinct is to blame the reflow profile. Engineers will spend days tweaking the soak zone or lowering the peak temperature by two degrees. This is a waste of time. You cannot reflow your way out of wet parts.

The crime didn’t happen in the oven; it happened on the storage shelf three days earlier.

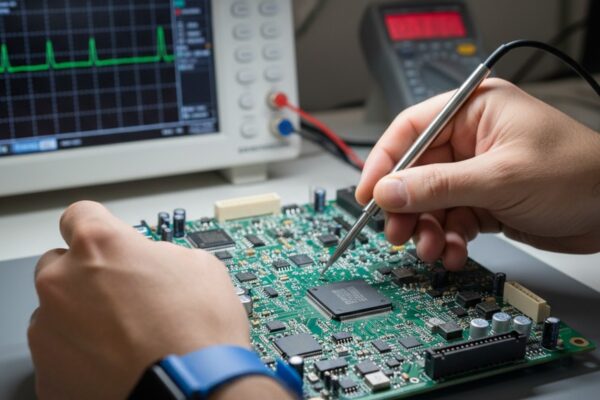

If you walk the production floor—not the guided tour path, but the back alleys behind the pick-and-place machines—you will find the root cause. You might see a “dry cabinet” where the digital readout says 5% RH, but the door hinge is broken and held shut with Kapton tape. The seal isn’t tight, and the real humidity inside is 55%, equal to the room.

You might spot reels of moisture-sensitive components sitting on a cart under an AC vent because the operator thought the “cool air” would keep them safe. You’ll find logbooks claiming a reel was returned to the dry box at 14:00, while the security camera shows it sat on a feeder trolley until the shift change at 18:00.

These violations are invisible to the data system. The MES (Manufacturing Execution System) says the part has 48 hours of floor life remaining. Physics says it saturated 12 hours ago. When that saturated part hits the 260°C peak of the reflow oven, the steam pressure does its work, regardless of how perfect your ramp-down rate is.

Stop Baking Your Way Out of Trouble

The most dangerous reaction to a moisture scare is the “Just Bake It” mentality. Production managers, terrified of scrapping $50,000 worth of sensors, will order a bake cycle to “reset” the floor life.

Baking isn’t a free reset button—it is a thermal stress event.

Standard ICs might tolerate a 125°C bake for 24 hours without complaint, but MEMS are far more fragile. I have seen trays of accelerometers baked at high temperatures where the outgassing from cheap shipping trays (which were not rated for baking) condensed onto the sensor ports, sealing them shut.

Even if you use the correct high-temperature JEDEC matrix trays, repeated baking promotes intermetallic growth at the lead interface and oxidizes the pads. You might dry the part out, but now you’ve created a “head-in-pillow” defect risk at soldering because the pads won’t wet properly.

Furthermore, if you try to bake parts that are still in the tape-and-reel, you are walking a razor’s edge. Most carrier tape cannot withstand standard bake temperatures. You end up with melted plastic fused to your components, or tape that warps just enough to jam the high-speed feeders, causing massive downtime.

If you must bake, you have to follow J-STD-033 strictly, often using low-temperature bakes (40°C) that take weeks, not hours. Most factories do not have the patience for this, so they crank the heat and cook the parts.

The MSL Clock is Absolute

The root of the discipline problem is often a misunderstanding of the Moisture Sensitivity Level (MSL) rating. Many teams treat MSL as a rough guideline. It is not. It is a calculated thermal limit.

There is a massive cliff between MSL 3 and MSL 5a.

- MSL 3 gives you 168 hours (one week) of exposure time.

- MSL 5a gives you 24 hours.

That is one day. If a reel of MSL 5a microphones is opened for a setup, left on the machine for a 10-hour shift, and then put back in a bag that isn’t perfectly evacuated, the clock does not stop. It pauses, at best. If the desiccant was already saturated, the clock keeps running inside the bag.

It is common to see firmware engineers trying to code around these failures. They see the sensor drift and try to build elaborate calibration tables or “burn-in” routines to stabilize the reading. This is futile. You cannot fix a delaminated die attach with software. You are calibrating a broken physical structure that will continue to move as humidity changes.

Protocol Over Heroics

The only fix for the “Walking Wounded” is aggressive, paranoid discipline before the oven.

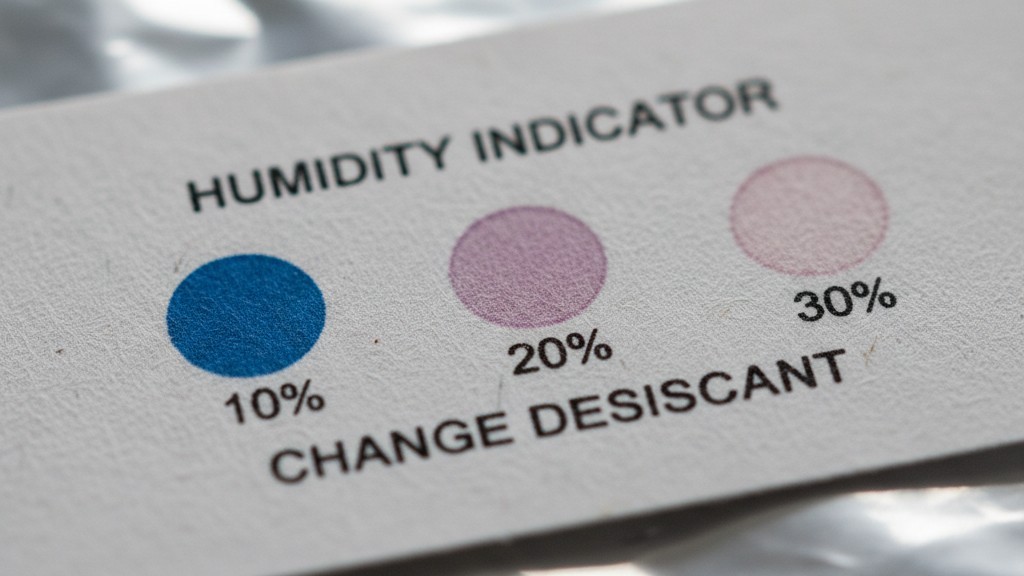

You must trust the chemistry, not the logbook. Every moisture barrier bag (MBB) has a Humidity Indicator Card (HIC) inside. When you open a bag, look at that card immediately. If the 10% spot is pink (or lavender, depending on the type), the parts are suspect, regardless of what the label says.

Check the vacuum seal on every bag before it is opened. If the bag is loose—if you can pinch the plastic and pull it away from the tray—it is compromised. The desiccant is likely saturated.

Finally, you have to be willing to scrap parts. This is the hardest sell to management. But a reel of MEMS sensors that has been left out for an unknown duration is a time bomb. If you put it on the board, it will pass the factory tests. It will ship. And it will fail when your customer takes it for a jog on a humid morning.

The cost of scrapping a $2,000 reel is a rounding error compared to the cost of a field recall. Don’t bake it. Don’t guess. If the chain of custody is broken, the part is trash.