The line goes down. The yield chart drops. A batch of boards fails functional test with intermittent shorts on the 12V rail. The immediate reaction from the production floor is to blame the pick-and-place machine. The reasoning seems sound: a high-speed nozzle slams a fragile ceramic component onto the board. If the component is cracked, surely the robot hit it too hard.

Engineers lose weeks calibrating nozzle pressure. They swap out feeders. They harass the vendor, claiming a “bad batch” of capacitors has contaminated the supply chain. This is the “Bad Batch” Fallacy—the comforting lie that purchasing bought defective parts, absolving the process team of responsibility. But modern placement machines from Panasonic, Fuji, or ASM have force feedback loops so sensitive they can detect a misalignment of microns. Unless an operator is crushing an 0201 with a nozzle meant for a D-pack, the machine is innocent.

The component didn’t break during placement. It broke later, when the board bent.

The Anatomy of the Chevron

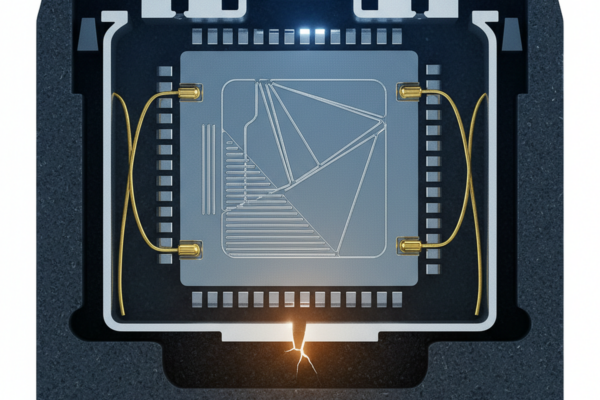

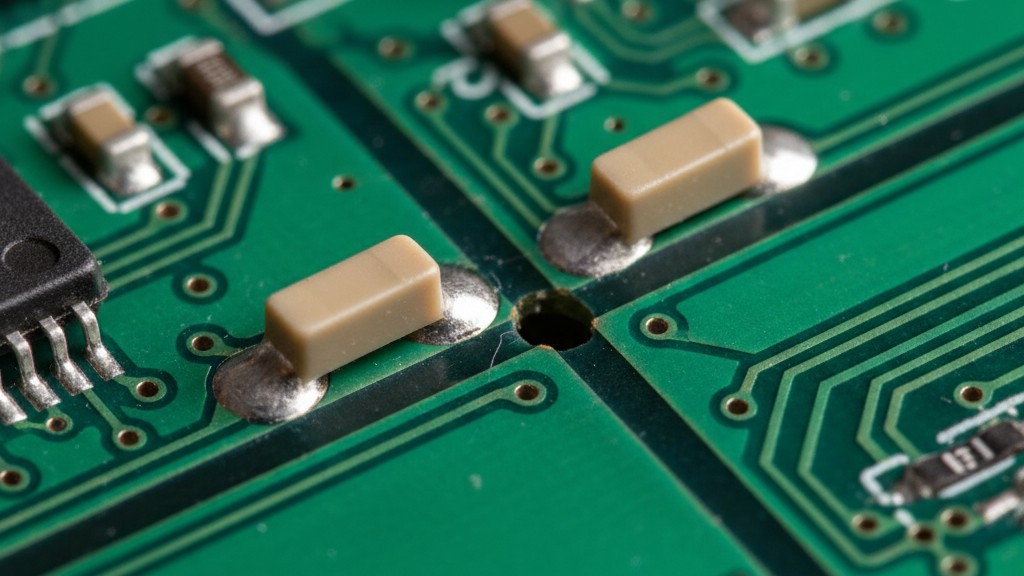

To see why the placement theory fails, look at the corpse. A ceramic capacitor (MLCC) is essentially a block of glass. It has high compressive strength but zero tensile flexibility. When a PCB bends, the fiberglass stretches. The rigid solder fillets transfer that stretch directly into the ceramic body.

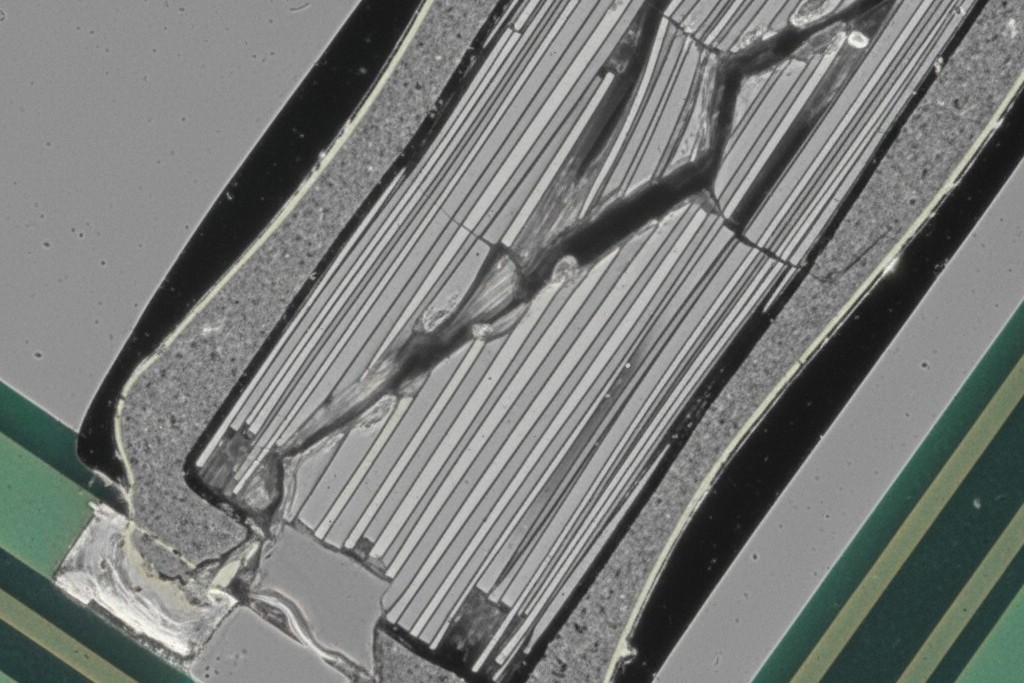

If the force came from a vertical impact—like a placement nozzle—the crack would look like a crater or a surface divot. That isn’t what kills yield. The killer is the flex crack.

Under a cross-section microscope, this failure has a distinct signature: the “chevron” or 45-degree crack. It initiates at the bottom corner of the capacitor, right where the termination meets the ceramic body, and propagates diagonally upward. This angle is the result of tensile stress pulling the bottom of the component apart as the board flexes underneath it. It’s a textbook shear failure—a physical record of a board bent beyond the ceramic’s strain limit.

The real danger here is stealth. Often, the crack is tight enough that the component passes In-Circuit Test (ICT) because the plates are still touching. But once the board heats up in operation or vibrates in the field, the crack opens. Moisture gets in. Insulation resistance drops. The capacitor shorts. A board that passed every factory test dies in the customer’s hands two months later.

The Crime Scene: Depaneling

If the placement machine didn’t bend the board, what did? The damage almost always occurs during depaneling—separating individual boards from the production panel.

The manual snap is the worst offender. In high-volume, cost-sensitive production—especially for consumer goods—panels are often scored with a V-groove (V-score) and separated by hand. Even worse, operators might use the “knee method” or the edge of a workbench to snap the panel. This applies massive, inconsistent torque. The FR4 fiberglass bends, but the solder joints don’t. The stress concentrates at the stiffest points on the board: the solder pads of large ceramic components.

Even “pizza cutter” style rolling blade separators are dangerous. If the blade height is set incorrectly, or if the operator pushes the panel through at a slight angle, the board bows. A V-score process relies on breaking the remaining web of material. That break is a violent mechanical event that sends a shockwave through the fiberglass.

The only safe method for high-reliability electronics is the router (tab-route). A router bit mills away the material, leaving no stress on the PCB. It’s slower, creates dust, and requires more maintenance. But it introduces zero bending stress. Managers often fight the switch to routers because of the cycle time penalty, calculating the cost of the bit versus the cheap V-score blade. They rarely calculate the cost of a 2% scrap rate or a $50,000 field recall caused by manual separation.

Geometry Is Destiny

If a router is impossible and V-score is mandatory, the survival of the capacitor comes down to layout. Two variables matter: Orientation and Distance.

Orientation is the single most ignored rule in PCB design. A capacitor placed parallel to the break line is in the kill zone. When the board bends along the V-score, the long axis of the capacitor stretches. The entire length of the component resists the bend, and it snaps.

Rotate that same component 90 degrees, so it is perpendicular to the break line. Now, when the board bends, the stress applies to the width of the component, not the length. The solder joints act as a pivot point rather than a rigid anchor, dropping the risk of cracking exponentially.

Then there is distance. Designers love to pack components right to the edge of the board to shrink the form factor. They rely on CAD Design Rule Checks (DRC) to flag if a part is too close. But standard DRC checks for electrical clearance (copper to copper), not mechanical safety. A capacitor can be electrically safe 1mm from the edge, but mechanically doomed.

The safe zone is typically 5mm from any break line. This varies, of course—a thick 1.6mm board transfers more stress than a thin 0.8mm one, and the glass weave direction matters. But 5mm is the standard “sleep at night” number. If a 1206 capacitor sits 2mm from a V-score, parallel to the cut, it’s not a matter of if it cracks, but when.

The “Soft Termination” Band-Aid

When layout cannot be changed—usually because the board is already spun and yield is crashing—engineers often reach for “Soft Termination” or “Flex-term” capacitors.

Standard capacitors use a rigid metal termination. Soft termination adds a layer of conductive epoxy resin between the copper and the nickel/tin plating. This resin acts as a shock absorber, allowing the termination to peel away slightly from the ceramic body during a bend. This breaks the electrical connection (fail open) rather than cracking the ceramic (fail short).

There is often confusion here, with purchasing managers asking if the extra cost is worth it. It works, but it isn’t magic. It increases the bending tolerance from perhaps 2mm of deflection to 5mm. Think of it as an airbag. An airbag reduces fatality rates, but it doesn’t mean you can drive into a brick wall at 60mph. If the depaneling process involves an operator snapping the board over their knee, soft termination won’t save the part. It’s a safety net, not a cure for a bad process.

Validation: The Smoking Gun

So, how do you prove to management that the process is at fault, not the vendor? The answer lies in destructive testing.

Send the failed board to the lab for a “Dye-and-Pry” test. The technician floods the area with red dye, places the board in a vacuum chamber to force the ink into any fissures, and then mechanically peels the component off the board. If there is red ink on the fracture face, the crack existed before the test.

If the ink reveals that signature 45-degree chevron, the argument is over. That is a flex crack. It didn’t happen at the vendor. It didn’t happen in the placement machine. It happened when the board was bent. Go walk the production line. Watch how the panels are separated. Listen for the snap. That sound is the sound of money leaving the factory.