The era of the static Bill of Materials is dead.

There was a time, perhaps a decade ago, when a design engineer could export a BOM from Altium, send it to a procurement desk, and expect every single Manufacturer Part Number (MPN) to be available on the shelf. That period was a historical anomaly. Today, we live in a reality of permanent allocation. A specific Murata capacitor or TI regulator might vanish from global inventory between the time you quote a board and the time you fund it.

The naive approach is to treat procurement as a clerical task—a simple game of matching strings of text in a spreadsheet. This is how product launches die.

When a specific part goes line-down—showing a 52-week lead time at the factory and zero stock at every major distributor—panic sets in. The clerical instinct is to find anything that fits the pads. If the original BOM called for a 10uF 0603 capacitor, the clerk looks for any available 10uF 0603 capacitor. They see the capacitance matches, the voltage rating looks okay, and the price is right. They buy it.

They have just planted a time bomb in the device. This isn’t a supply chain success; it is an engineering failure waiting to manifest in the thermal chamber or, worse, in the hands of a customer.

Procurement is an Engineering Discipline

We operate on a fundamental conviction: procurement isn’t an administrative function. It is a sub-discipline of electrical engineering.

When we handle turnkey projects, we do not simply hand a list of part numbers to a buyer. We hand a set of parametric requirements to an engineer who understands the physics of the components. The distinction is vital because the “exact match” mentality is fragile. If you rely on a single string of characters from a single vendor, your product is at the mercy of that vendor’s production schedule. If you rely on parametric guardrails—defining the component by what it does rather than what it is named—you gain resilience.

This is often where friction arises with those accustomed to the consignment model. There is a specific anxiety about handing over procurement control—a fear that “turnkey” means “loss of oversight.” In reality, the opposite is true. A designer buying parts on a credit card is often operating with limited visibility, checking one or two distributors. An engineering-led procurement team scrutinizes the entire market through the lens of parametric data.

We aren’t just looking for a part that fits. We are looking for a part that performs, and we do it with volume leverage that a single project cannot command. The goal is to move from a fragile dependency on a specific brand to a robust dependency on a specific set of electrical specifications.

The Silent Killer in the Bill of Materials

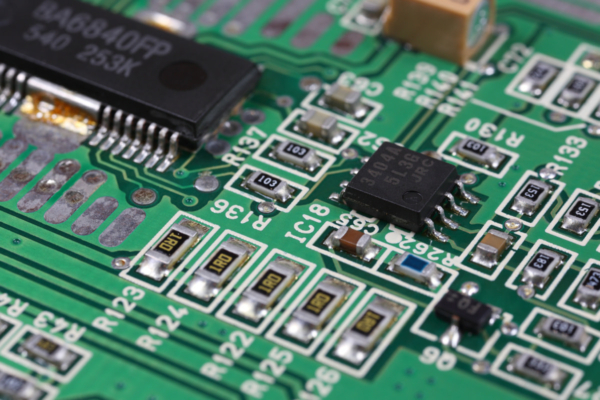

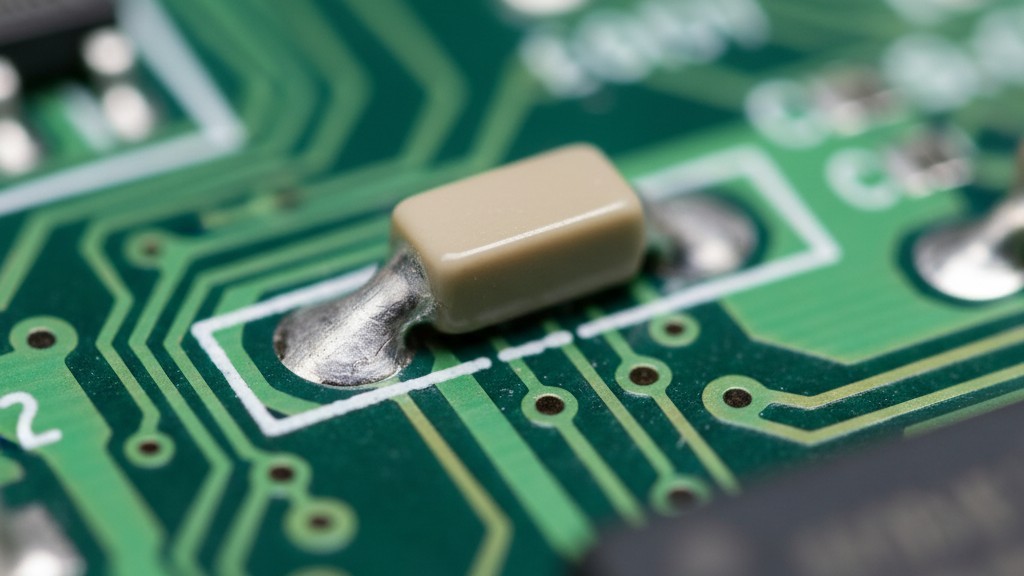

The danger of the clerical approach lies in the physics of a “simple” passive component. Consider the Multi-Layer Ceramic Capacitor (MLCC). It is the most common component on any modern PCB, and the most frequent victim of bad substitutions.

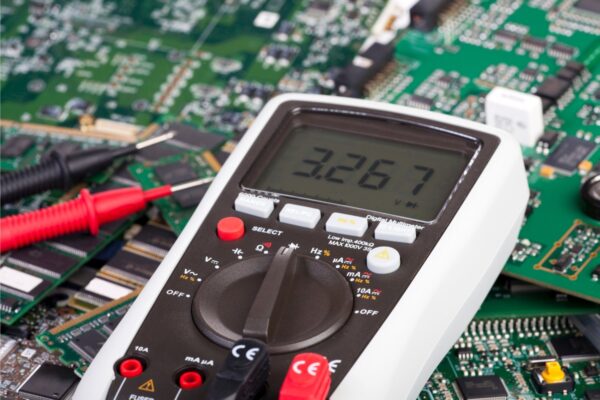

A buyer sees “10uF, 16V, 0603” and assumes all parts with that label are identical. They are not. The hidden variable that destroys circuits is DC Bias—the tendency of high-k dielectrics to lose capacitance when a DC voltage is applied.

We have seen this scenario play out with painful regularity. A client specifies a high-quality X7R dielectric capacitor. It goes out of stock. A well-meaning purchaser swaps it for a “functionally equivalent” part with a Y5V or generic “High-K” dielectric to keep the line moving. On the bench, at room temperature and zero bias, the part measures 10uF. It looks perfect.

But once that board powers up and 12V is applied to the rail, the effective capacitance of that generic substitute might drop by 80%. Suddenly, your 10uF bulk capacitor is behaving like a 2uF capacitor.

The consequences are rarely immediate. The board will likely pass a basic functional test. But in the field, or under load, ripple voltage increases. The microcontroller resets randomly. Sensors drift. We recall a specific instance involving a dashboard cluster where a generic capacitor swap caused the MCU to reset every time the ambient temperature hit 85°C. The “savings” on that swap were fractions of a penny; the cost of the recall was existential.

This is why we do not allow substitutions based on top-level specs alone. We overlay the DC bias curves. We check the temperature coefficient. If the datasheet doesn’t provide a DC bias curve, we don’t buy the part.

The Provenance Trap

The second great danger in the allocation era is the “Grey Market.” When authorized channels—DigiKey, Mouser, Arrow, Avnet—run dry, desperation leads many to the brokers. These are unverified vendors who claim to have 5,000 pieces of a chip that the manufacturer says hasn’t been produced in six months. It is tempting. When a project is stalled, and a broker in Florida claims to have stock, the “Just Buy It” impulse is overwhelming.

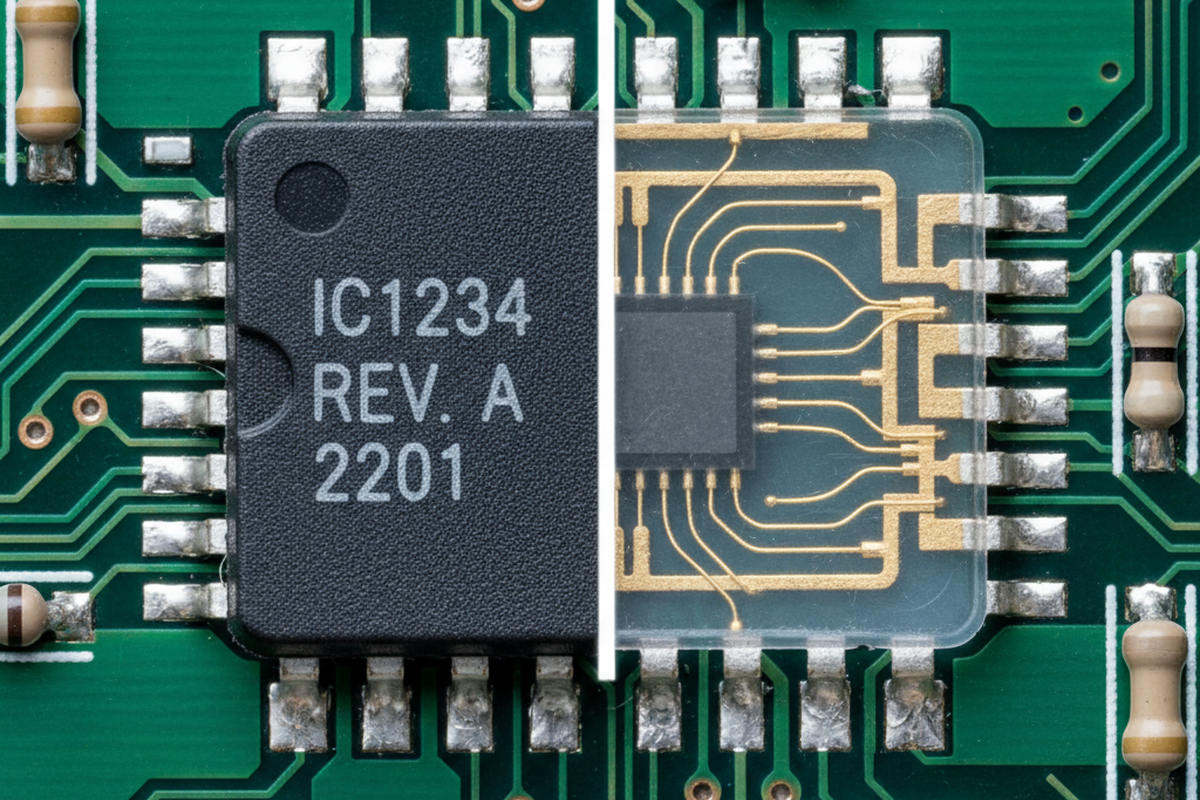

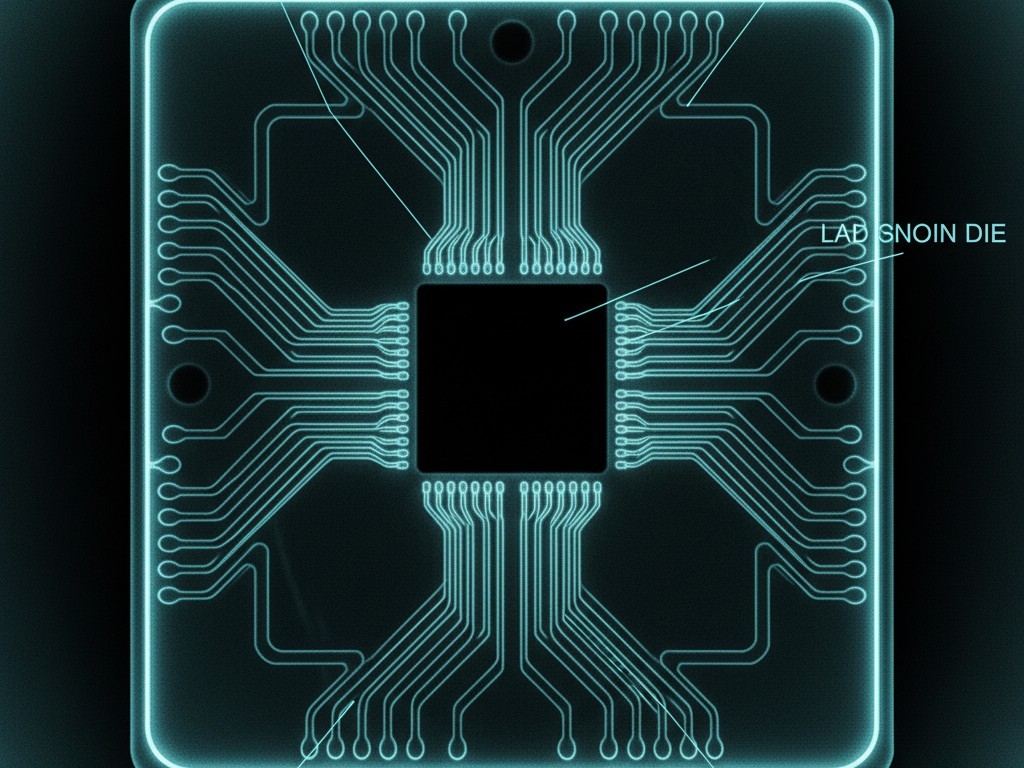

We take a Red Team approach to this inventory: assume it is fake until proven otherwise. The counterfeit market has evolved. We are no longer just seeing empty packages or wrong parts. We see “sanded-toppers”—parts where the original markings are sanded off and new, higher-spec markings are laser-etched on. We see “ghost reels” where a lower-grade version of a chip is repackaged as the premium automotive-grade version.

In one case, we inspected a reel of TI power regulators sourced from a secondary channel. The labels were perfect. The moisture sensitivity packaging looked authentic. But an X-ray analysis of the lead frame revealed the silicon die was half the size of the genuine part. It was a functional part, but it would have failed under full load.

The only defense against this is strict adherence to authorized provenance. If we cannot trace the chain of custody back to the factory, we do not solder it to the board. Traceability is more than paperwork; it is the only proof that the silicon inside the package matches the datasheet you designed against.

Regaining Control Through Parametric Rigor

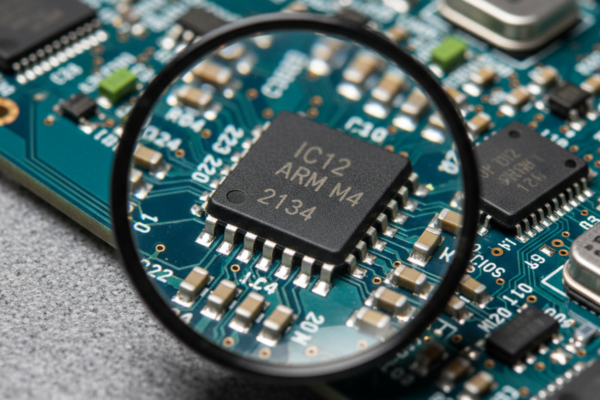

To navigate shortages without falling into these traps, we use a method called the Datasheet Overlay. When a primary part is unavailable, we don’t look for a “cross-reference” listed in a distributor’s database, as those are often riddled with errors. We pull the datasheets of the primary part and the proposed alternate and place them side-by-side.

We look for deviations. Does the Samsung alternative have a slightly different Land Pattern than the TDK original? Is the ESR (Equivalent Series Resistance) higher? We explicitly validate the critical parameters that software filters often miss. This allows us to confidently switch between brands—using a Samsung MLCC instead of a Murata, or a Yageo resistor instead of a Vishay—knowing that the physics are aligned. This engineering rigor allows us to unlock inventory that a rigid “MPN Exact Match” policy would miss. We aren’t guessing; we are calculating the margin of safety.

Designing for Availability

The battle for inventory is often won or lost before the BOM is even exported. We constantly urge engineers to practice Design for Availability (DFA). This means avoiding single-source parts whenever possible. If you design in a connector that is only made by one niche manufacturer, and they have a factory fire or an EOL (End of Life) event, you are stuck. There is no parametric equivalent for a unique physical shape.

We also recommend flexibility on passive footprints. In the heat of the 2021 shortages, we saw 0402 capacitors vanish while 0603s were plentiful, and vice versa. If you are in the layout phase, consider whether you can accommodate a dual-footprint or ensure your density allows for a slightly larger case size if needed. It is a small move in Altium that can save weeks of heartache later.

The market will remain volatile. Prices will fluctuate, and lead times will drift. We cannot control the global supply chain, but we can control our reaction to it. By treating procurement as an engineering challenge—focusing on parametric truth and authorized provenance—we turn a chaotic market into a manageable variable. The goal isn’t just getting the boards built. It’s ensuring that the board you built today works exactly like the one you designed yesterday.