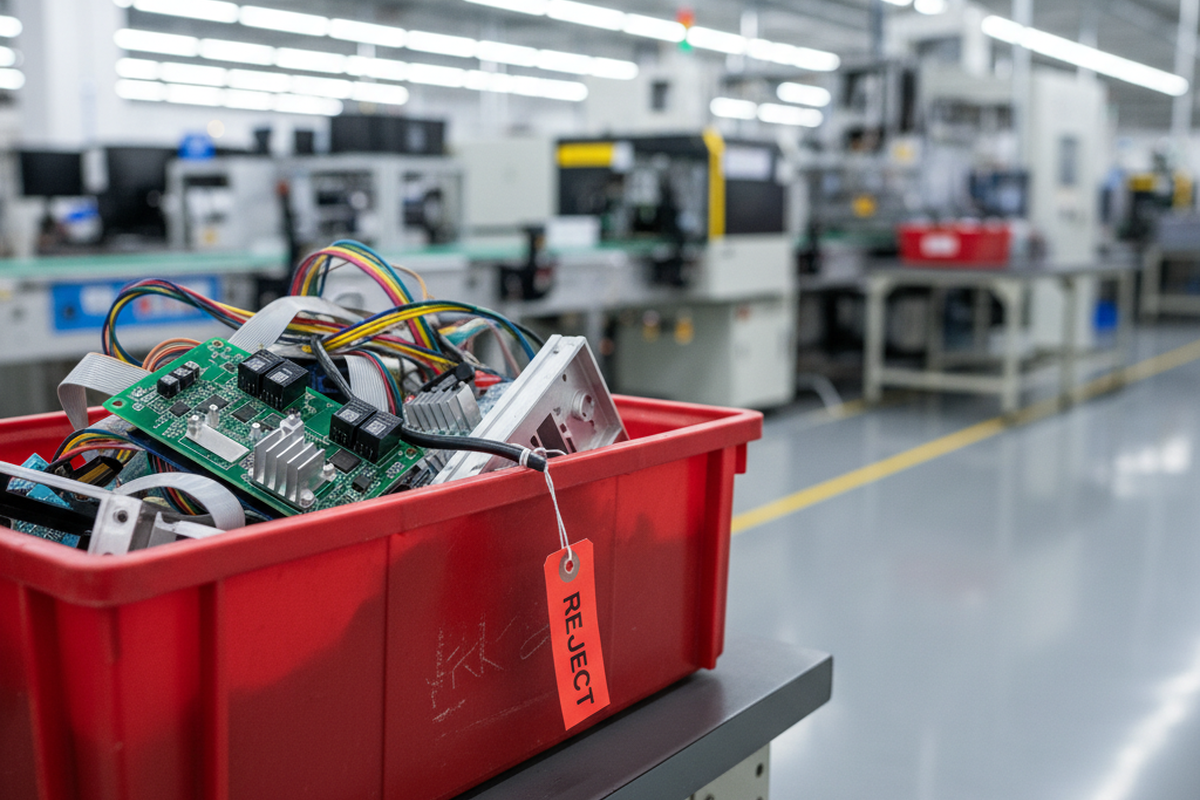

You can walk into a contract manufacturer’s facility in Guadalajara or Shenzhen on any given Tuesday and witness a perfectly executed disaster. The line moves, the pick-and-place machines hum, and the operators follow their traveler documents with precision. Yet, at the end of the line, the red reject bins fill up with units that physically rattle, overheat, or simply refuse to boot.

The operators aren’t failing at assembly; the system is failing at synchronization.

In one common scenario, a mechanical team issues an Engineering Change Order (ECO) to modify a heat sink, the packaging team issues a separate ECO for new foam inserts, and the firmware team pushes a patch to lower fan speeds. If these three changes arrive at the factory without explicit linking, the line supervisor implements them as they clear approval. You end up with 2,000 units containing the old, small heat sink but running the new, low-speed fan profile. The result is a thermal shutdown in the field, all because the “Effectivity Date” on the firmware change was set to “Upon Approval” while the mechanical change was set to “Exhaust Stock.”

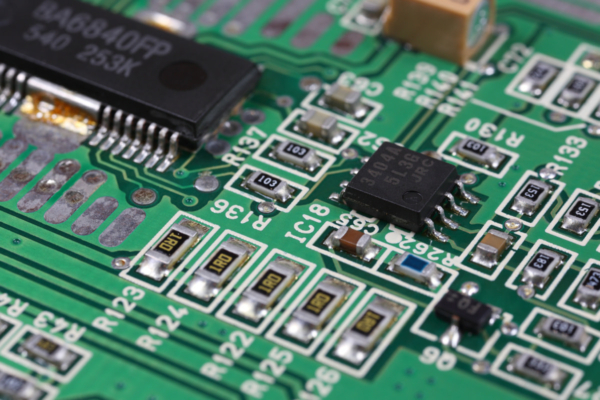

Engineering usually works fine. The friction comes from treating engineering as a continuous flow while manufacturing happens in discrete snapshots. When you treat a Bill of Materials (BOM) like a software repository, you invite chaos. A git revert costs nothing. Reverting a plastic injection mold tool or scrapping 5,000 printed circuit boards because the revision letter didn’t match the stencil is a six-figure mistake. The collision of multiple ECOs during a scheduled build is the single most common cause of “soft” yield loss. You haven’t built the unit wrong; you’ve just built the wrong unit because timelines collided.

The Trap of “Latest Revision”

There is a dangerous assumption in modern hardware development that the “latest” version of a file is the one that should be built. In a Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) system, a file can be “Approved” long before it is “Implemented.” That gap is where the money vanishes.

An engineer sitting in an Austin office sees that the new bracket design is approved in the system and assumes the next unit off the line will have it. But the factory floor operates on physical inventory, not digital status. If there are 4,000 units of the old bracket in the warehouse, the factory’s default logic is to use them up to avoid waste. Unless the ECO explicitly forces a “Purge and Scrap” action, the “latest” revision exists only on the server, not on the line.

This disconnect becomes lethal when you introduce the “Deviation Waiver.” Often a necessary evil in supply chain management, a waiver is formal permission to break the rules temporarily—perhaps to use a substitute capacitor during a shortage or skip a cosmetic test to meet a shipping deadline. The danger arises when these waivers are treated as administrative paperwork rather than engineering changes.

A waiver is effectively a temporary ECO with an expiration date. If you authorize a deviation to use a broker-sourced component but fail to link that deviation to a specific range of serial numbers in the PLM, you have created a time bomb. Six months later, when those components fail, you won’t know which units have them. You cannot recall just the bad ones because the data doesn’t exist. Without a specific implementation gate, the factory defaults to whatever is on the shelf, and “hope” is not a valid field in a traceability log.

Firmware Is a Component, Not a Vibe

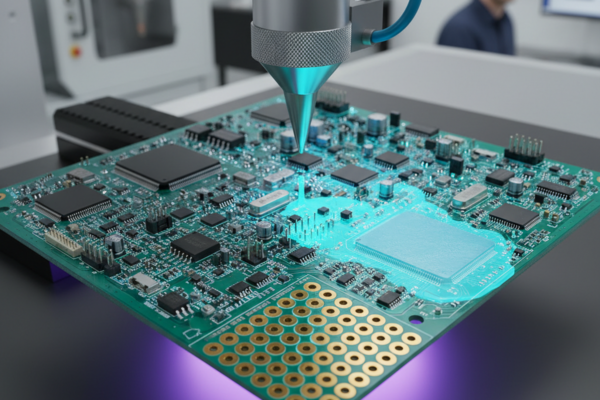

The most frequent victim of revision collision is firmware. Software teams are accustomed to continuous integration; they see code as a living, breathing entity that improves over time. Manufacturing sees code as a part, no different from a screw or a resistor. If the firmware binary does not have a distinct part number and a revision controlled in the BOM, it effectively does not exist to the line operator.

Consider the “Phantom Firmware” scenario. A developer pushes version 2.1 to the repository to fix a critical bug. The factory programmers, however, are flashing the binary located in a specific folder on the test server. If the ECO process does not explicitly instruct the test engineer to validate the new checksum and update the programmer image, the factory will continue to flash version 2.0 forever. The units will pass functional test because the test limits likely haven’t been updated to look for the new version string either.

There is a temptation here to rely on Over-the-Air (OTA) updates to fix these messes later. This is a dangerous crutch. OTA cannot fix a device that bricks immediately upon boot because the bootloader version doesn’t match the application partition map. Furthermore, relying on field updates destroys your ability to diagnose failures. If a customer calls support with a bricked unit, and your RMA team cannot tell from the serial number what code was originally flashed at the factory, they are flying blind. They don’t know if they are chasing a hardware defect or a software bug. If the binary does not have a part number, it does not exist to the line operator, and it certainly won’t help your support team.

The Disposition Matrix

The most critical field on any ECO is not the description of the change, but the “Disposition” of the old material. This is where the financial reality of the change is calculated. When you introduce a new revision, you must account for the material in four states: On Hand (in the warehouse), On Order (inbound from vendors), WIP (Work in Process on the line), and Finished Goods (sitting on the dock).

For each category, you must make a binary choice: Use As Is, Rework, Return to Vendor, or Scrap. This is the Disposition Matrix. Many engineering managers leave this section blank or vague, writing things like “Rework if possible.” This is a dereliction of duty. “Rework” implies labor hours, disassembly, potential damage to other components, and re-testing. Often, the cost of unboxing, opening, desoldering, and re-flashing a unit exceeds the margin of the device.

You must run the math. It is frequently cheaper to scrap $5,000 of raw PCBs than to pay for three days of line-down time while operators attempt a delicate rework. Rework is almost always a fantasy; scrap is the price of clarity.

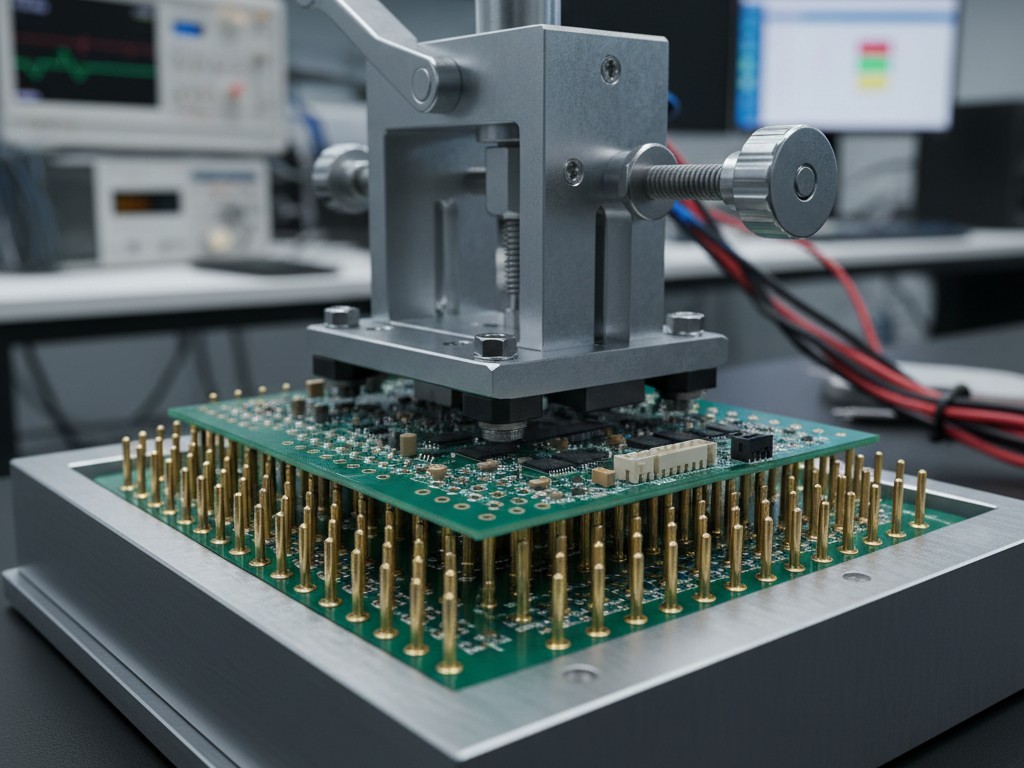

The Clean Break Protocol

To stop the bleeding, you must enforce the “Clean Break.” A rolling change—where new revisions are mixed into the bin with old revisions—is acceptable only for parts that are 100% form, fit, and function interchangeable, like a screw from a different vendor. For everything else, you need a hard cut.

This means defining the cut-in point not by a calendar date, which is slippery, but by a specific lot code or serial number. “Revision B starts at SN: 100500.” This instruction allows the factory to segregate the line. They can finish the run of Revision A, clear the line, purge the old stock, and begin Revision B with a fresh setup.

It requires discipline. It might mean delaying a build by two days to wait for the new parts to arrive rather than building a “hybrid” monster. But that delay is cheaper than a recall. Control the break point, or the break point will control your margin.