The failure report always looks the same. A fleet of ruggedized control modules—designed for abuse, rated for IP67, and potted for survival—starts behaving erratically in the field. The relays stick, or they don’t switch at all. The sensors drift. The customer sends the units back to the lab, furious.

The bench tech powers them up, and they work perfectly. They stamp “No Trouble Found” (NTF) on the ticket and send the unit back. Two weeks later, it fails again.

This isn’t a software bug or a bad batch of relays. It’s a chemistry problem. Specifically, it is the result of a “safe” material behaving according to the laws of physics rather than the promises of a marketing brochure. The culprit is almost certainly the silicone sealant used to protect the device. In the hermetic silence of a sealed enclosure, that silicone has been slowly dismantling the electromechanical integrity of the system, turning the very contacts intended to conduct electricity into microscopic shards of glass.

The Mechanism of the Kill

Silicone is deceptive because it appears solid. To the naked eye, a cured RTV (Room Temperature Vulcanizing) gasket or potting compound looks like a stable, rubbery block. To a chemist, however, it’s a gel-like matrix of polymer chains that never truly stops moving.

Standard silicone formulations contain short-chain molecules called cyclic siloxanes. These low-molecular-weight volatiles don’t lock into the cured matrix; they remain free to migrate. At room temperature, they possess a high vapor pressure, meaning they constantly outgas from the bulk material. In an open environment, these vapors dissipate harmlessly into the atmosphere. But in a sealed enclosure—the kind designed to keep water out—these vapors are trapped. They saturate the internal air volume until they reach equilibrium.

The vapor itself is electrically insulating, but that isn’t the primary failure mode. The destruction happens when the vapor meets an electrical arc.

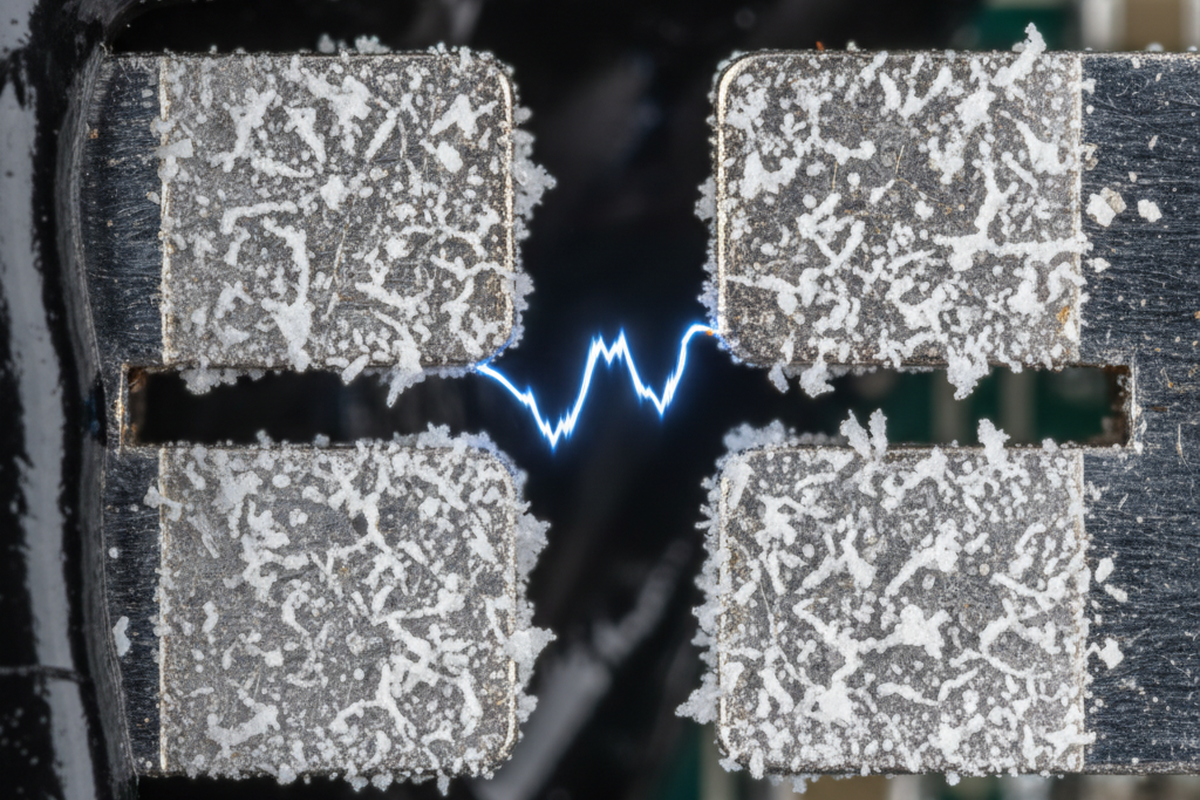

When a relay switches or a brushed motor spins, it generates a microscopic plasma arc. If siloxane vapor is present in the air gap, the energy of the arc decomposes the complex silicone molecule ($Si-O-Si$). The carbon and hydrogen components burn off, leaving behind pure Silicon Dioxide ($SiO_2$).

Silicon Dioxide is sand. Glass, effectively—and one of the best electrical insulators known to man.

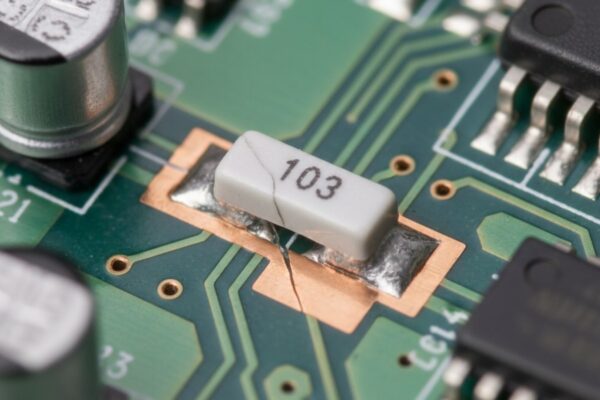

With every switch cycle, a fresh layer of nanoscopic glass deposits directly onto the mating surfaces of the contact. It accumulates in layers. Eventually, the relay closes mechanically, but the circuit remains electrically open. The contact resistance spikes from milliohms to ohms, then to megohms. The signal dies.

The “Waterproof” Fallacy

There is a dangerous instinct in hardware design to solve reliability problems by sealing them in a box. The logic is sound for moisture: keep the rain out, keep the circuit dry. But for chemical contamination, a seal is a trap.

By sealing a device to IP67 or IP68 standards without accounting for internal outgassing, the enclosure becomes a reaction chamber. The concentration of volatiles that would be negligible in a vented housing builds up to critical levels. These volatiles migrate through wire insulation, plastic connector housings, and into “sealed” components. A standard “sealed” relay is not hermetic; it is plastic-sealed. Silicone vapor, having a lower surface tension and smaller molecular size than water, permeates the epoxy seal of the relay over time. Once inside, it waits for the spark.

The “Electronic Grade” Trap

The most common defense against this failure mode is the purchase order. The Bill of Materials lists “Electronic Grade” silicone. The tube says “Neutral Cure.” The engineers assume this means the material is safe for sensitive electronics.

This is a misunderstanding of terms.

“Electronic Grade” or “Neutral Cure” usually refers to the curing chemistry. Standard bathroom caulk is acetoxy cure; it releases acetic acid as it sets. You can smell the vinegar. This acid eats copper traces and corrodes solder joints. “Neutral Cure” (often alkoxy or oxime cure) replaces the acid with alcohol or other non-corrosive byproducts.

While this prevents corrosion, it does nothing to stop siloxane outgassing. A silicone can be perfectly non-corrosive to copper while still pumping enough volatile siloxanes into the air to destroy a contact switch in 10,000 cycles. The lack of a vinegar smell isn’t a safety certification; it’s simply the absence of one specific acid. The alcohol smell of an alkoxy cure is still evidence of volatiles leaving the matrix. Unless the datasheet explicitly quantifies the mass loss, “Electronic Grade” is just marketing fluff, not an engineering specification.

The Only Standard That Matters: ASTM E595

If you are designing sealed electronics with moving contacts or precision optics, there is only one way to spec silicone: you must demand data compliant with ASTM E595.

This standard, originally developed for the space industry to prevent optics from fogging on satellites, is the only rigorous definition of “low outgassing.” It involves heating a sample to 125°C in a vacuum for 24 hours and measuring what comes off.

You are looking for two numbers:

- TML (Total Mass Loss): Must be $< 1.0%$.

- CVCM (Collected Volatile Condensable Materials): Must be $< 0.1%$.

If a vendor cannot provide these numbers for a specific batch, the material is suspect. Many commercial “low volatile” silicones will show TML values of 3% or higher when tested. That missing mass is what coats your optics and insulates your switches.

Be aware that even within “safe” materials, batch-to-batch variation exists. The “Low Volatile” version of a product might just be the standard version that was baked longer at the factory. Unless you are buying materials with lot-specific certification (often designated as space-grade or controlled volatility), you are trusting a statistical average.

Mitigation and Material Selection

The harsh reality is that silicone and electromechanical contacts are fundamentally incompatible in sealed systems. If your device contains relays, switches, slip rings, or brushed motors, silicone should be banned from the BOM.

The Alternatives:

- Urethane: Two-part urethane potting compounds are generally safe. They do not outgas siloxanes because they contain no silicon backbone. They are harder to rework and can be sensitive to moisture during cure, but they will not ghost-kill your relays.

- Epoxy: Excellent chemical stability and low outgassing, but rigid. High thermal stress can crack components.

- Baking: If you must use a specific silicone, a post-cure bake-out (e.g., 4 to 8 hours at 80°C+ depending on the component thermal limits) can drive off the majority of volatiles before the unit is sealed. Think of this as mitigation rather than a cure. It reduces the reservoir of volatiles but does not eliminate the generation mechanism.

Some engineers argue that silicone is necessary for thermal shock protection. It is true that silicone has unmatched flexibility across temperature extremes. However, a device that survives thermal shock but fails to conduct electricity is still a failed device. If thermal cycling is the primary concern, design the mechanical stress relief into the housing or the board layout, rather than relying on a chemical that compromises the electrical function.

The Cost of Convenience

Silicone is popular for a reason. It is easy to dispense, cures at room temperature, handles high heat, and can be peeled off for rework. It is convenient for the manufacturing floor.

That convenience is paid for by the reliability team. The cost of switching to a urethane or epoxy system—dealing with mix ratios, pot life, and harder rework—is negligible compared to the cost of a field recall. When a thousand units start failing intermittently in the field, and the root cause is a microscopic layer of glass that disappears when you scrub the contact, you will wish you had chosen the difficult material.

If it is sealed, and it switches, keep the silicone out.