The defect is almost always visible if you know when to look, but most process engineers are looking at the wrong time. You walk the line, check the printer, and see a crisp, square deposit on the pads. The definition is sharp. The volume is correct. The SPI (Solder Paste Inspection) machine gives it a green light. Yet twenty minutes later, after that same board has traveled down the conveyor and exited the reflow oven, you are staring at a bridged QFN or a massive void under a power FET.

The immediate instinct is to blame the reflow profile or the stencil aperture design, but the crime didn’t happen in the oven. It happened in the ten minutes the board sat waiting on the conveyor.

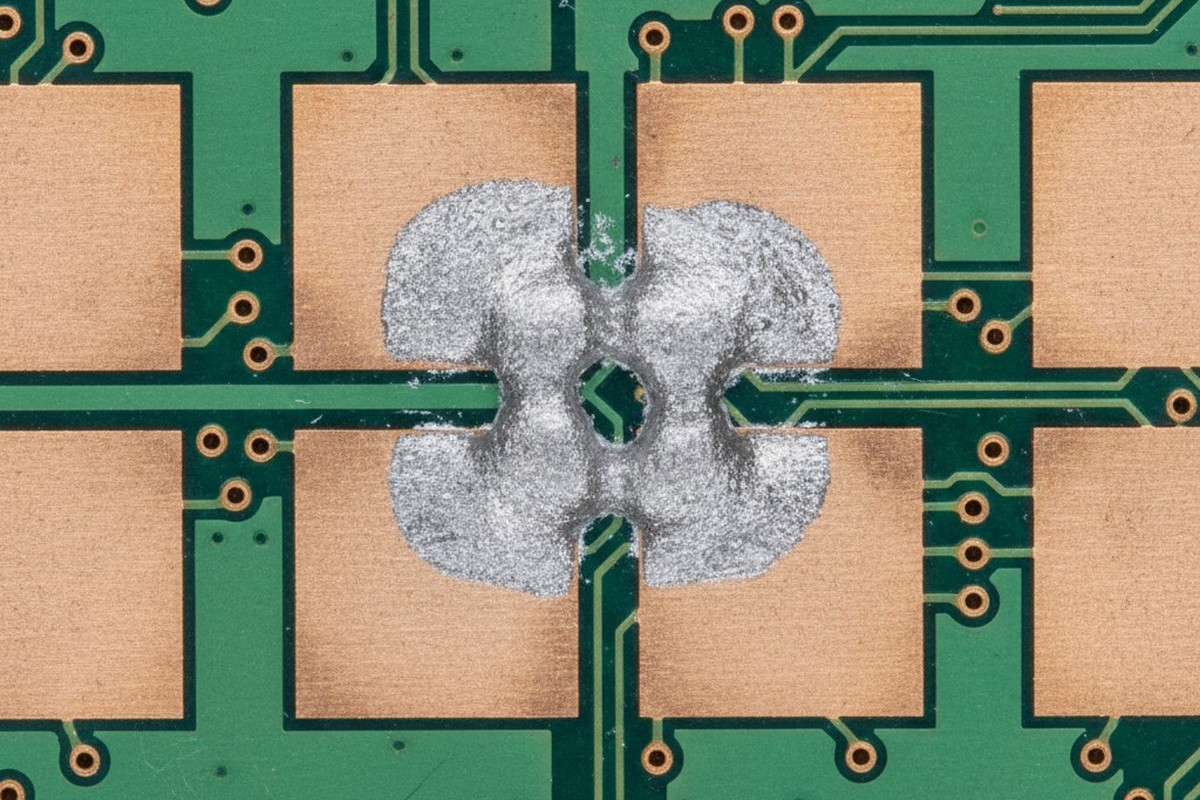

We call this “cold slump,” the silent killer of First Pass Yield (FPY). Technically a fluid, solder paste begins to relax and spread under its own weight before it ever sees heat. In a pristine lab environment, this effect is minimal. But in a real factory—where humidity fluctuates and the AC struggles against the heat of the reflow ovens—cold slump turns sharp brick-like deposits into amorphous blobs that touch their neighbors. By the time the board enters the pre-heat zone, the bridge has already formed. No amount of profile tweaking will separate two pads that have already merged. Heat isn’t the problem. The physics of the paste sitting at room temperature is.

The Physics of the Collapse

To understand why paste fails while doing nothing, look at the material itself. Solder paste isn’t simple glue. It is a dense suspension of metal spheres (powder) floating in a chemical vehicle (flux). The magic of printing relies on thixotropy. When the squeegee pushes the paste across the stencil, shear force lowers the paste’s viscosity, allowing it to flow like liquid into the apertures. The moment the squeegee passes and the stencil lifts, that shear force stops. Ideally, the paste should instantly recover its high viscosity and “freeze” in that perfect brick shape.

But recovery is never instant, and it is never permanent. The flux vehicle fights gravity and surface tension constantly. If viscosity doesn’t recover fast enough, the heavy metal particles—remember, this is mostly tin and silver—drag the flux outward. This is the slump: a slow-motion collapse. On a 0.5mm pitch QFP or a tight QFN thermal pad, you only have a few mils of gap. If the paste slumps just 10%, that gap disappears.

Engineers often try to fight this by redesigning the stencil. They request “home plate” or “inverted home plate” apertures to reduce the volume of paste, hoping that less paste means less spreading. This is an engineering band-aid on a physics problem. Reducing the volume gives you less solder to form the joint, potentially leading to starve-outs or weak mechanical bonds, and it doesn’t solve the root issue. If the paste’s rheology is broken, a smaller deposit will still slump; it just takes a few minutes longer to do it.

The Hygroscopic Threat

The primary driver of this viscosity breakdown usually isn’t the paste formulation itself—modern SAC305 Type 4 pastes are chemically robust. It is an invisible ingredient: water. Flux chemistries are naturally hygroscopic. They absorb moisture from the air like a sponge. When you leave a jar open or a glob of paste on the stencil, it actively pulls water molecules out of the factory air.

This absorbed water destroys the delicate chemical balance of the flux. It acts as a thinner, drastically lowering viscosity and ruining slump resistance. You might not see it with the naked eye, but a rheometer would show the yield stress plummeting. If your factory floor is running at 70% Relative Humidity (RH) because it’s a rainy Tuesday and the facility manager is trying to save money on climate control, your paste is degrading exponentially faster than the datasheet claims.

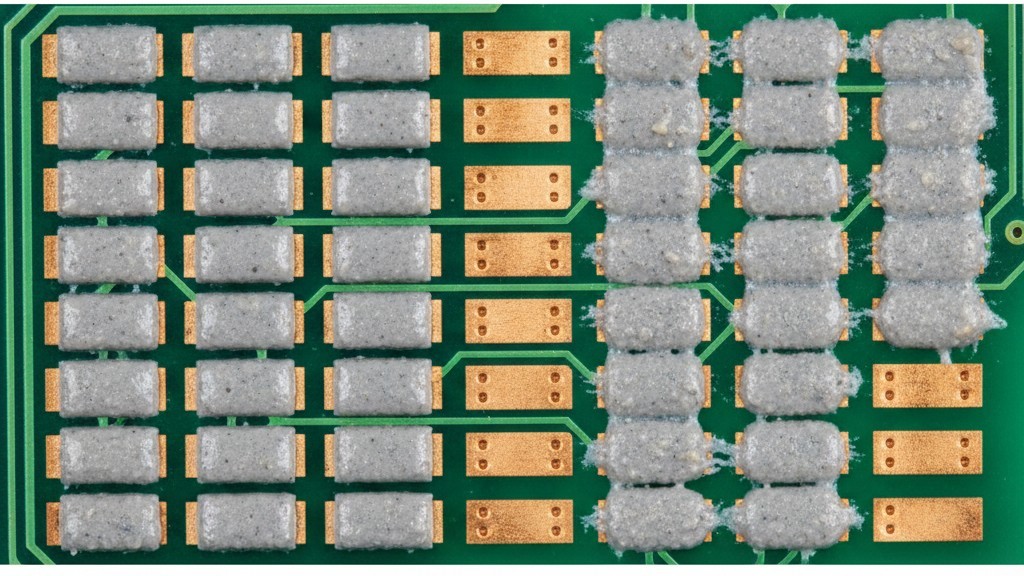

The consequences go beyond just bridging. That water doesn’t just sit there; it boils. When the board hits the reflow oven, the water trapped inside the paste turns to steam instantly. This micro-explosion blows the solder powder apart. If you are chasing intermittent “solder balling” or “mid-chip beads”—those tiny metal spheres stuck to the side of a capacitor—stop looking at your reflow profile ramp rate. You are likely boiling water. The steam creates voids inside the joint and sprays solder balls outside of it. You are fighting a moisture problem masquerading as a thermal one.

The Cold Chain Broken

The most egregious handling error, however, happens before the paste even reaches the printer. It happens in the transition from storage to the line. Solder paste is perishable. It is stored at 4°C to pause the chemical reaction between the flux and the powder. If that reaction runs, the flux gets used up while sitting in the jar. But cold storage creates a trap.

Consider the timeline of a “bad batch.” The logs show the paste was taken out of the fridge at 7:00 AM for the shift start. The defect—massive bridging and voiding—starts appearing at 9:00 AM. The operator claims they followed procedure. But if you look closely at the “paste out” log, you might find the jar was opened immediately. When you open a 4°C jar in a 25°C room with 60% humidity, condensation forms instantly on the cool surface of the paste. Think of a cold beer sweating on a patio—it’s the same physics. That condensation is pure water, and you just mixed it directly into your chemistry.

The storage equipment itself is often a culprit. It is common to see a factory running million-dollar SMT lines relying on a $90 dorm-room mini-fridge to store fifty thousand dollars worth of inventory. These consumer appliances have terrible thermal hysteresis. They cycle wildly, sometimes freezing the paste (which ruins the flux suspension permanently) and other times letting it drift up to 15°C. If the paste freezes, the flux separates. No amount of mixing will fix it. If you see separation or “crust” on a new jar, check the fridge, not the vendor.

A pervasive myth suggests you can “quick temper” paste by putting it on a heater or mixing it vigorously. This is false. The only safe way to temper paste is to take it out of the fridge and let it sit, sealed, at room temperature for at least four to eight hours. If you didn’t plan ahead and you need paste now, you are out of luck. Breaking the seal early guarantees moisture intake.

Scraping the Bottom

The final enemy of yield is misplaced frugality. Solder paste is expensive, often costing hundreds of dollars per kilogram. This leads managers and operators to treat it like liquid gold, trying to save every gram. You see operators scraping the dried, crusty paste from the far edges of the squeegee travel and putting it back into the jar, or mixing it with fresh paste.

This “scraper’s economy” is mathematically ruinous. That used paste has been exposed to air for hours. Its flux is exhausted, its viscosity shot. It has absorbed moisture and oxidation. By mixing it back in, you contaminate the fresh material. Consider the ratio: 50 grams of wasted paste costs perhaps three dollars. A single reworked BGA board costs fifty dollars in technician time, plus the risk of scrapping the whole PCBA. If you save three dollars to risk fifty, you aren’t saving money.

Similarly, there is constant pressure to extend shelf life. “It expired last week, can we still use it?” The answer should always be no. The chemical degradation of the flux is not a suggestion; it is a reality. The risk of voiding and open joints increases daily past the expiration. If you are asking this question, your inventory management is the problem, not the expiration date.

Discipline is the Fix

The solution to cold slump and “mystery” defects is rarely a new, expensive alloy or a nanocoated stencil. It is boring, rigorous discipline. It is buying a $20 thermometer and hygrometer and placing it right next to the printer. It is enforcing a strict “Do Not Open” time on paste removed from cold storage. It is empowering operators to throw away paste that has been on the stencil too long, rather than trying to save it.

Process control beats material science. You can run the most expensive, slump-resistant Type 5 paste in the world, but if you treat it like dirt—if you let it get wet, freeze it, or leave it out for 24 hours—it will fail. Conversely, a disciplined line can run standard SAC305 in a controlled environment and achieve near-zero defect rates. The paste usually works. Make sure the environment lets it.