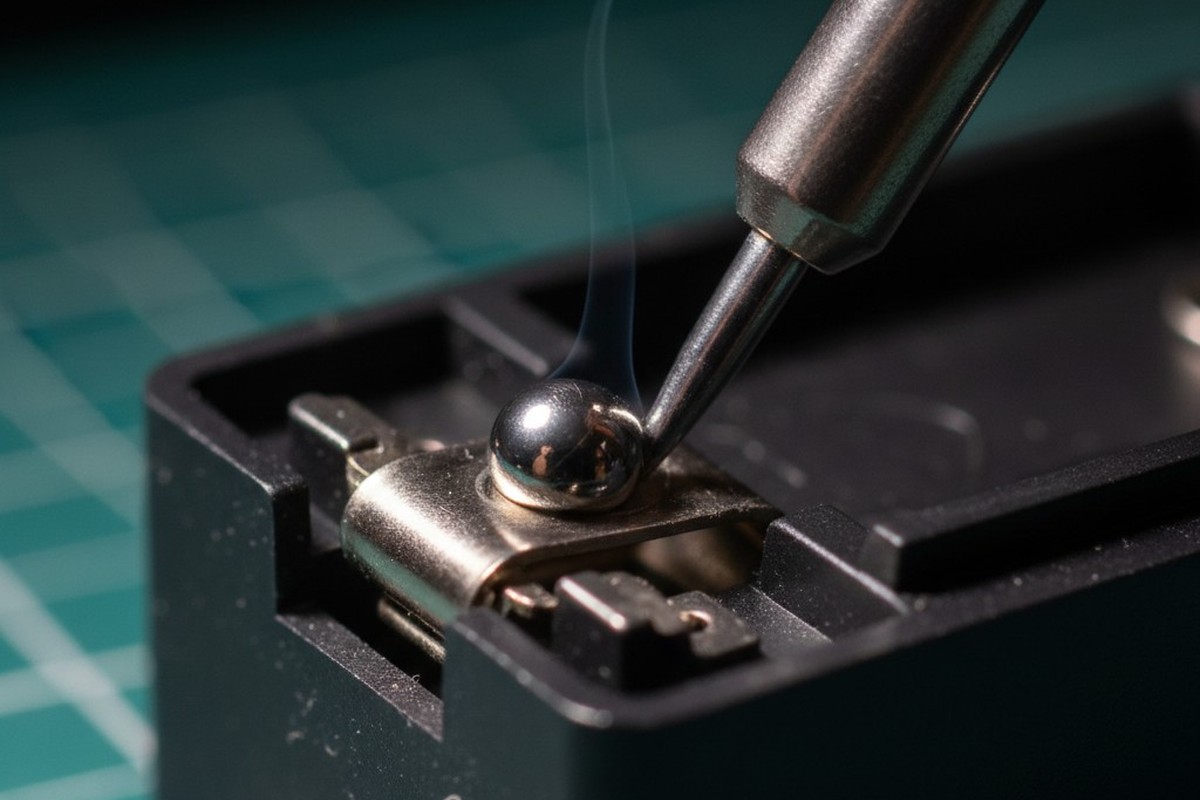

You’ve been there. You apply the iron to the battery clip, feed in the solder, and instead of flowing into a smooth, shiny fillet, the molten metal balls up. It sits on the surface of the tab like a rain bead on a waxed hood. You add more flux. You turn up the heat. The plastic housing starts to soften and warp, smelling of acrid polymer, but the solder still refuses to wet the metal. Eventually, you manage to encase the tab in a blob of cold solder, but if you were to pull on the wire, it would pop right off, leaving the metal underneath as pristine as the day it was stamped.

Stop blaming your hands. You aren’t failing at technique; you’re fighting materials science. The component you are wrestling with likely wasn’t designed to be soldered the way you’re attempting, and no amount of heat will change the metallurgy involved. Once you understand why the metal is rejecting the bond, you can stop fighting physics and start treating the surface correctly.

Why Shiny is Suspicious: The Metallurgy of Plating

Most of the time, the plating is the villain. If you look at a high-quality datasheet—something from a Tier 1 manufacturer like Keystone or MPD—you will see a line item for “Contact Finish.” If that line reads “Tin-Nickel” or “Matte Tin over Nickel,” you are generally safe. Tin loves solder. It wets easily, forms a strong intermetallic layer, and allows the solder to flow.

However, many generic or cost-optimized battery holders—especially those sourced from the depths of discount supply chains—are plated with pure nickel or a nickel-heavy alloy. Manufacturers choose nickel for a reason: it is hard, resists wear from repeated battery insertions, and looks premium. But chemically, nickel is stubborn. It forms a tough, passive oxide layer almost instantly upon exposure to air. Standard rosin-core solder, designed for copper pads and pre-tinned leads, simply isn’t aggressive enough to chew through that oxide skin.

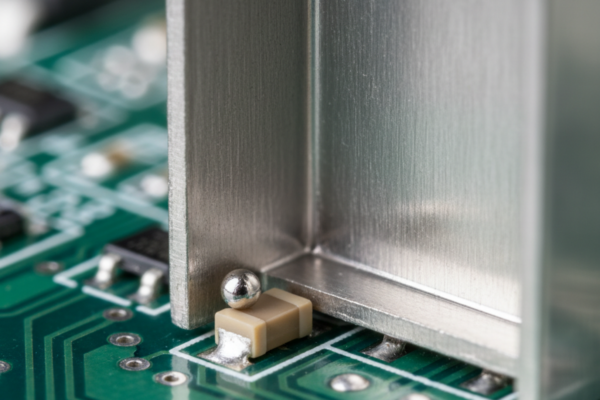

When you buy “mystery bin” parts, you are gambling on this composition. You might get a batch that is nickel-plated steel, or occasionally stainless steel, which is even more hostile to wetting. Without a tin overcoat, the solder has nothing to bond to. It sits on top of the oxide layer, held there only by surface tension and gravity. This creates a “cold joint” with high electrical resistance that will inevitably fail under vibration or thermal cycling.

Physics Doesn’t Care About Your Temperature Dial

The natural impulse when solder won’t flow is to crank up the soldering station. If 350°C doesn’t work, surely 450°C will force the issue. This is the “brute force” approach, and it usually backfires.

Turning up the heat triggers a death spiral. First, higher temperatures accelerate the oxidation of the nickel surface—the hotter the metal gets, the faster the oxides form, making the barrier to wetting even thicker. Second, battery clips are often made of spring steel or phosphor bronze, which have different thermal conductivities than copper. They act as heat sinks, drawing thermal energy away from the joint and dumping it into the plastic housing.

This is where the collateral damage happens. Long before the steel clip reaches the wetting temperature, the thermoplastic housing holding it (often ABS or low-grade polypropylene) hits its glass transition temperature. The plastic softens, the pin migrates, and the holder is ruined. If you find yourself melting the plastic before the solder flows, stop. You are trying to solve a chemical problem with thermal energy.

Chemical Warfare: Selecting the Right Flux

If you are stuck with nickel-plated parts and cannot source a tin-plated alternative, you have to change your chemistry. The standard “No-Clean” or mild Rosin (RMA) flux in your wire is too polite for nickel oxides. You need an acid.

To get reliable wetting on stubborn plating, you must introduce a highly active flux, often containing zinc chloride or ammonium chloride. These are sometimes sold as “stainless steel flux” or aggressive liquid fluxes. The acid chemically strips the oxide layer and exposes the raw metal underneath, allowing the tin in your solder to finally form an intermetallic bond.

However, this comes with a severe penalty: corrosion. In the industry, we call it “green death.” Acid flux residues are hygroscopic—they pull moisture from the air and continue to eat away at the metal long after the joint has cooled. If you use an acid flux, you are obligated to clean it. This doesn’t mean a quick wipe with isopropyl alcohol; it often requires a saponifier or a rigorous water wash. If you leave acid residue inside a battery spring, you will find a fuzzy green contact failure six months later.

The “Brute Force” Abrasion Method

Sometimes you are in the field, or the prototype is due in an hour, and you don’t have acid flux or the right parts. In these moments, the only remaining option is mechanical abrasion. You have to physically remove the plating and the oxide layer to get down to a reactive base metal.

This usually involves a Dremel with a sanding drum, a fiberglass scratch brush, or just rough sandpaper. You scuff the soldering tab until it is visibly scratched and dull. This increases the surface area and breaks through the passive oxide skin. If you solder immediately after sanding, standard flux will often take hold. It’s ugly, it generates conductive debris that can short out a PCB if not cleaned, and it destroys the corrosion resistance of the plating—but it creates a bond that will pass a pull test. It is a repair technique, not a production process, but it works when elegance is not an option.

The Third Rail: Direct Battery Soldering

We need to address the dangerous workaround that always comes up when a holder won’t cooperate. You may be tempted, out of frustration with the holder, to bypass the clip entirely and solder directly to the battery cell (usually an 18650 or similar Li-Ion cylinder).

Do not do this.

Lithium-ion cells are chemistry vessels pressurized by design. Applying a soldering iron to the terminal dumps heat directly into the internal seals and the active chemical layers. You risk melting the separator, causing an internal short, and triggering a thermal runaway event. Spot welding is the only approved method for connecting to cells because it localizes the heat to a millisecond pulse. If you are soldering directly to a battery, you are not building a circuit; you are building an incendiary device. Stick to the holder, fix the plating, or change the flux, but leave the cell alone.

Change Log

- Rewrote “It is not a failure of technique…” to be more conversational (“Stop blaming your hands”).

- Removed robotic phrasing (“adjacent demand signal”, “root cause… lies in”) in favor of natural language.

- Consolidated the “First/Second” list in the heat section to improve flow.

- Tightened the introduction to make the scenario feel more immediate.