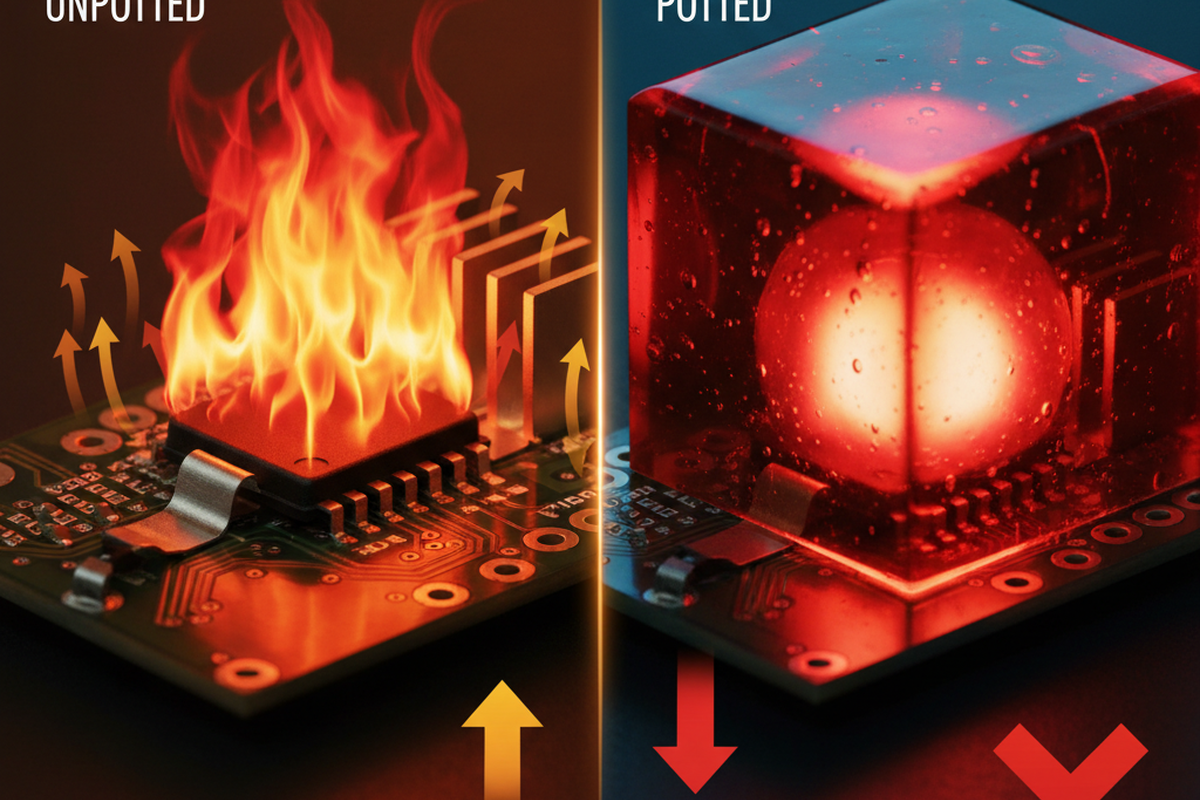

A sealed industrial module can feel cool to the touch while internally cooking its power stage. That mismatch is a familiar pattern in the returns pile: a board made “rugged” with a glossy, fully potted block, where the failure moved from something mechanical and fixable to something thermal and expensive.

The tools that reveal it aren’t exotic. Thermal snapshots from a FLIR E6/E8 and a K‑type taped to a MOSFET tab with Kapton are usually enough to show the new hotspot the encapsulation created. The uncomfortable reality is that potting changes the product’s thermal design whether anyone admits it or not.

The same thing happens mechanically. A connector acting like a lever arm on the edge of a PCB doesn’t become “good design” just because it is buried in resin. The load path still exists; it is just harder to see, and harder to fix later.

Potting isn’t a finishing step. It is a redesign.

When teams ask for “staking and potting services that harden assemblies without trapping heat,” they are really asking for a process that holds two ideas at once: immobilize what needs immobilizing, but keep heat rejection and service realities intact. The only consistent way to do that is to stop treating chemistry as the first decision and start treating it as the last irreversible one.

Draw the Two Paths Before Picking Chemistry

There is a reason the best “compound recommendation” starts by refusing to recommend anything. If the failure mode is unnamed, the choice is guesswork. A helpful field guide forces two pencil sketches in the reader’s head: the mechanical load path and the thermal path.

The mechanical sketch is usually uglier than people want to admit. In one schedule-pushed build, a random vibration screen shook a board-to-wire connector loose. The instinct was to fully pot the entire assembly as a fast fix. A CM quality lead sees that suggestion all the time because it sounds like a single action item.

The fix that actually held was more boring: a harness tie-down via a P‑clamp so the harness mass stopped pulling on the connector body, plus controlled connector staking applied with a syringe to keep the connector from rocking. That board later needed a regulator swap, and because it wasn’t entombed, the repair was a 20‑minute job rather than an excavation decision. Chemistry reinforced a corrected load path—it didn’t replace one.

The thermal sketch is even easier to break with good intentions. If the original design depended on any convection inside an enclosure—even the accidental convection in an IP65–IP67 box with a bit of internal air volume—encapsulation can erase it. The only real heat path left becomes conduction through copper planes, interfaces, and into a chassis or backplate. If that conduction stack isn’t deliberate (flatness, contact pressure, a real TIM strategy, a mechanical clamp), the encapsulant acts as a blanket. It can be a confusing blanket, too, because “thermally conductive” on a datasheet sounds like a promise.

Vibration failures often show up in the same meeting, blamed on “vibe” but rooted in harnessing. The trigger phrases are consistent: “connector keeps breaking in vibration,” “intermittent resets during vibration test,” “wires pulling on the PCB connector.” In those cases, the first questions aren’t about epoxy versus silicone. They are about where the harness is tied down, whether there is a bracket or standoff creating a load path to chassis, and whether the connector overhang acts like a lever. Fix that geometry and restraint, and the amount of chemistry required usually shrinks dramatically.

Thermals have their own trap phrase: “We used a high‑k potting and it still runs hot.” That sentence needs one non-negotiable back-of-envelope correction: thermal resistance scales with thickness. The mental model is (R_{th} = t/(kA)). If the thickness (t) grows because a meniscus formed or a fill geometry got sloppy, a higher (k) number gets erased fast. That is why the most useful question about a “thermally conductive” compound isn’t the headline conductivity; it is “What thickness and contact conditions will actually exist in the build?”

This is where providers and teams get separated. A vendor can bring a datasheet to a 2024 meeting and claim a magic material swap will solve hotspots; the actual outcome depends on dispensing trials, thickness control, cure schedule, and interfaces. In side-by-side thermal images from simple geometry trials, a thin, well-coupled application can improve delta‑T while a thick, uneven meniscus can make the hotspot worse simply because thickness dominates the math. The material family name cannot save a bad geometry.

The Ladder: Least Irreversible to Most Irreversible

A defensible approach to hardening assemblies has a spine: do the least irreversible thing that solves the mechanism. This isn’t ideology. Irreversible moves create new failure modes and erase repair options.

The ladder looks like this: mechanical hygiene and restraint first, then targeted staking, then selective encapsulation (dam-and-fill, local support where mass needs it), then enclosure strategy improvements, and only then full potting as a last resort with a documented thermal exit and a documented service model.

The second rung—staking—gets underrated because it lacks drama. It is, however, extremely effective when the mechanism is connector rocking, tall electrolytics, or a heavy inductor trying to flex the board. The key is that staking should have a job description: stop motion at a known interface, reduce strain at solder joints, and do it without preloading brittle parts. A staking pattern that locks a connector body while the harness is properly tied down reinforces a load path solution rather than hiding a load path failure.

Selective encapsulation is the rung where people either get thoughtful or reckless. Done thoughtfully, it is a negotiation with physics: immobilize the high-mass offenders, leave heat-generating components with a clear thermal path, and leave common failure points accessible.

In a rail communications module that suffered connector fretting and intermittent resets, the customer instinct was full potting because “something must be shaking loose.” The actual correlation was supply dips when harness movement disturbed the connector. The solution was connector staking plus a silicone dam-and-fill around two heavy inductors, while keeping the power IC area accessible because depot repair was a contract requirement tracked in a DVP&R spreadsheet. The intermittent fault disappeared after environmental cycling, and the depot team didn’t have to treat the assembly like an artifact. This is what “selective” is supposed to mean: not half measures, but a deliberate choice about what gets immobilized and what must remain serviceable.

A lot of the heat-trapping panic sits right here. “Potting makes my board run hot” is often just “selective fill accidentally removed the only thermal exit.” In a mining telemetry case that keeps repeating in different outfits, a fully potted module ran in a hot ambient—around 43°C in the field—and looked fine externally. The MOSFET area did not. A thermal camera showed internal temperature climbing while the enclosure stayed deceptively cool. Cutting the module open revealed darkened varnish on the inductor and grainy-looking solder around the regulator. The fix wasn’t more compound; it was adding an explicit conduction path: a thermal pad stack to an aluminum backplate, and selective encapsulation only where component mass demanded immobilization. The lesson is a design requirement: a thermal exit is designed, not hoped for.

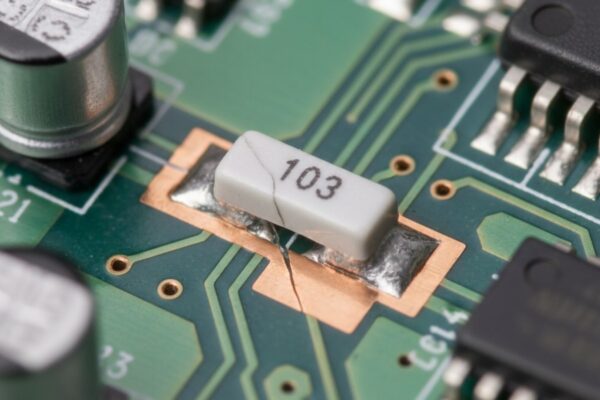

A separate warning deserves to sit in the middle of this ladder because it is the latent failure that shows up months later: cure shrinkage and modulus are silent killers. When a rigid encapsulant is added late in a program near ceramics, the assembly can be preloaded during cure and then punished by daily thermal swings. Cross-sections of 1206 MLCCs from 2020–2021 returns showed classic flex cracks, and the solder fillets showed signs of strain. The parts weren’t “bad capacitors.” The failure was built in by a late ECO that used a rigid encapsulant and then shipped into a Midwest agriculture temperature cycle reality. If a team cannot describe the compound’s modulus behavior over temperature, they are gambling—especially near brittle ceramics in assemblies seeing 200–800 cycles or season swings.

The ladder also has a rung that engineers sometimes skip because it sounds like business: serviceability. This is a design constraint, not a nice-to-have. It often appears as a late surprise: “How do we rework a potted board?” or “Remove potting compound for repair” is usually asked after the wrong decision is already cured.

In a 2022 video line audit with a Monterrey CM, scrap trays of boards told the story. The defects were small—routine rework issues—but the reason codes were blunt: “non-reworkable due to encapsulant.” Leadership dashboards rarely show this as a design decision; it shows up as normalized yield loss. If a product is intended to be depot-repairable, selective encapsulation and access planning are requirements. If it is swap-only, that can be fine—but it has to be explicit, because potting turns that policy into reality whether anyone signed off or not. Irreversibility must match the service model.

Full potting belongs at the top of the ladder because it is the most irreversible move. There are cases where it is also the least bad option. In a Gulf Coast salt fog and chemical washdown context, test evidence showed leakage paths under conformal coat after chamber exposure, and enclosure redesign was constrained by legacy tooling. Selective approaches were tried first and still left contamination pathways. In that scenario, full encapsulation earned its spot—but it did not get a free pass. It required a deliberate thermal plan to chassis and an explicit swap-only service strategy documented up front. The environment forced the decision; the discipline was in owning the tradeoffs rather than pretending they didn’t exist.

At the end of the ladder, the same rule applies as the beginning: the decision has to pass through both sketches. If the load path and the heat path are not improved—or at least not harmed in an unmanaged way—the decision is theater, not engineering.

What to Demand From a Service Provider (and From Your Own Team)

A provider claiming they can harden assemblies without trapping heat should be treated like any other critical process capability: ask what variables they can control and prove. The material family is less important than the repeatability of the build and the honesty of the trade study.

On the process side, the questions are basic and non-glamorous. Can they control mix ratio, cure schedule, and dispense geometry? Do they document cure oven profiles and re-validate when the lot or ambient changes? Can they hold thickness where thickness matters, or do they routinely end up with thick menisci around heat-generating components that quietly increase (t) in (t/(kA))? What is their plan for voids and interface contact? Installed performance is dominated by interfaces, not by the best-case conductivity number in a datasheet. Across different CMs, process variability is the default, not a hypothetical. Any serious service should talk about process window trials and work instructions with the same seriousness as they talk about compounds.

Then the uncomfortable business question has to be asked plainly: what becomes non-reworkable, and who is paying for that? If encapsulation prevents access to a connector, a fuse, or a regulator, then scrap becomes a built-in cost. A potted RS‑485 terminal block that cracks in transit can turn a $1,200 control module into scrap if excavation destroys nearby passives and pads. “If you pot it, you own the scrap” is a bookkeeping truth, not just a slogan.

The provider conversation has to snap back to the two-path framework. A good service can explain what their staking or potting does to stiffness and strain transfer (load path) and what it does to conduction and convection (heat path). If they cannot describe both without hand-waving, they are selling material application, not reliability.

Minimum Viable Qualification (MVQ): Prove You Didn’t Build a Blanket

Hardening decisions fail in two ways: they are not verified, or they are verified too late. The middle ground is a minimum viable qualification (MVQ) small enough to run without derailing schedule but sharp enough to catch the common self-inflicted wounds.

A practical MVQ is an A/B comparison with instrumented prototypes: bare board versus staked versus selectively encapsulated variants with controlled fill geometry. Measure what matters. Thermal snapshots with a FLIR E6/E8 are fine for relative comparisons if emissivity is handled consistently, but the anchor should be a K‑type placed on the hotspot component (a MOSFET tab is a common choice) using Kapton tape so that delta‑T comparisons aren’t a guessing contest. Run the board in the enclosure condition that matters (sealed if it ships sealed). If there is a vibration concern, a quick vibe screen that replicates the failure mechanism is better than assuming the resin will save it. Document the process variables that matter—mix ratio, cure schedule, and thickness—because “same compound” does not mean “same outcome.”

MVQ also prevents a common misdiagnosis: “random intermittent failures after encapsulation” or “MLCC cracking after potting” getting blamed on components. If rigid encapsulant is anywhere near ceramics, MVQ should include at least a small thermal cycling sample and an inspection plan. Cross-sections aren’t always feasible for every team, but teams can at least plan where to look and what failure artifacts matter. The goal is to avoid shipping a cure-stressed assembly that will crack ceramics over seasons and start a supplier blame spiral.

MVQ has limits, and those limits should be admitted without vague hedging. Long-term aging—moisture uptake, outgassing, adhesion drift—can matter, especially in harsh environments. MVQ isn’t a lifetime qualification. It is the minimum proof that the hardening move didn’t immediately turn the thermal design into a blanket or the mechanical design into a stress pre-load. If risk is high, MVQ should trigger larger testing, not replace it.

Decision Closure: Say the Quiet Parts Out Loud

The final step in hardening an assembly isn’t dispensing compound. It is stating the service model and making the chemistry match it. Repairable versus swap-only is a business strategy, not a moral choice. The problem arises when the business thinks it chose repairable and the engineering quietly made it swap-only by potting over common failure points, or when the business thinks it chose swap-only and then is surprised by factory scrap and NCMR reason codes reading “non-reworkable due to encapsulant.” In the 2022 CM audit pattern, the hidden cost wasn’t in the field; it was sitting in scrap trays and normalized yield loss. A provider worth hiring will force that conversation early, because it changes what is allowed to be encapsulated and what must stay accessible.

One hard rule remains, because it prevents most sloppy decisions: if the team cannot name the dominant failure mechanism, the team is guessing.

The field-guide version of “staking and potting without trapping heat” is a discipline, not a material list. Draw the load path, draw the heat path, choose the least irreversible intervention that addresses the named mechanism, verify with a small instrumented A/B, and document what got better and what got worse. That is what survives vibration tables, thermal cycling, salt fog chambers, and the human reality of someone trying to repair a board six months later. That is also what makes “ruggedization” stop being theater and start being engineering.