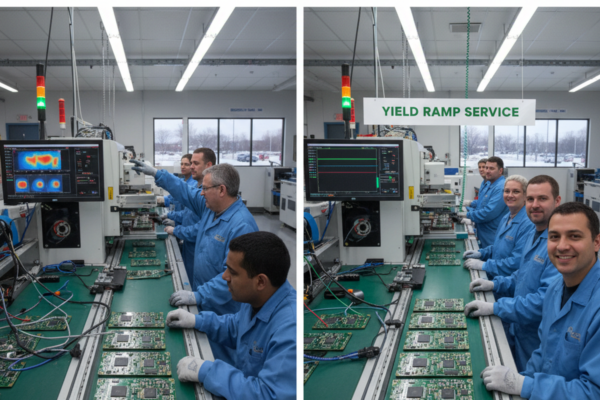

On an overnight shift in Tijuana in late 2018, a line stopped for hours because a “beautiful” ICT fixture started failing boards at random. The fixture looked like a museum piece: machined parts, bespoke harnessing, even an embedded controller meant to make sequencing “simple.” None of that mattered at 2 a.m. when worn probes and a cracked solder joint inside the fixture turned into intermittent opens that looked like product defects. The only person who really knew how to service it had left a couple of months earlier. Operators swapped boards. Engineers argued about assembly. Yield fell off a cliff anyway. The lesson wasn’t poetic—it was operational: if a tired tech can’t service the fixture mid-shift, it’s not production-ready.

That story is why the “fixture-as-a-service” conversation exists at all. Teams haven’t suddenly fallen in love with CapEx; they just know the gap between “flying probe is fine” and “full ICT program” is where mid-volume programs bleed schedule and ship bad boards. Most organizations simply aren’t staffed to own a custom test product on top of the actual product they’re trying to ship.

When someone’s default question is, “Do we need a full ICT program?” they usually aren’t asking a technical question. They’re asking a panic question.

Do the Bottleneck Math Before You Buy a Philosophy

Before anyone argues about coverage, they need a throughput number that can survive a production meeting. Back in 2017, one program targeting roughly 1,500 units per week started with flying probe because it was quick and didn’t require a fixture. Cycle time hovered in the 4–6 minute range per board, plus handling. That doesn’t sound tragic until it becomes a staffing plan. Even if a team assumes generous uptime—because nobody ever admits downtime on a slide deck—minutes per board multiplied by boards per week turns into “how many lanes” and “how many people” fast.

Here’s the uncomfortable part of that math. A single flying probe lane can look “cheaper” because a fixture quote is a line item, while overtime is a smear across payroll and missed ship dates. But if the output target requires parallel lanes, the team is already paying fixture money—just distributed across overtime, extra machines, retest loops, and operator variability. Add a second shift and the station is still the pacing item if the physics don’t cooperate. Add a third shift and maintenance and handling discipline become the gating factors. Asking “Can we just use flying probe?” is often another way of saying “We don’t want to admit test is the bottleneck.”

If planned weekly output requires more than one flying-probe lane, you are already in fixture territory.

For an ops director or a CFO-adjacent decision-maker, that’s the translation that matters: cycle time becomes headcount, and headcount becomes risk. It’s not just labor cost; it’s schedule certainty. That certainty is the difference between shipping on time versus explaining missed dates and growing RMAs in an 8D.

What You’re Actually Buying: Minimum Viable Fixture-as-a-Service

Recently, a CTO at a ~60-person hardware company kept asking a question that sounded simple: “How much does an ICT program cost?” On the surface, it’s a pricing question. In practice, it’s a bandwidth question. The team was shipping mid-volume, coordinating across time zones with a CM quality engineer, and living inside ECO churn. They didn’t need a lecture about how ICT works. They needed a deliverable they could plan around.

That’s the first mental shift: a bed-of-nails fixture “as a service” isn’t just hardware—it’s ownership. It is the difference between buying a base and inheriting every future failure mode: pin wear, plate updates, alignment drift after shipping, and those “urgent” emails when yield drops for reasons nobody can reproduce at the bench. When someone asks, “Do you build fixtures for us?” the real question is usually, “Who owns the fix when the fixture starts lying?”

A minimum viable fixture-as-a-service, for a mid-volume product that cannot wait, is usually a system with boring parts: a modular base, a probe plate that can be replaced without rebuilding the world, a defined pin ecosystem (with documented tip options and force/travel assumptions), and a documentation pack that the CM can execute without escalating across PST–CST–Malaysia time. The deliverable is also a process: how updates happen when the PCB spins, who stocks spare pins, and what response time looks like when yield drifts. If that sounds like an SLA, it should.

The second shift is accepting that rev churn is not an exception in mid-volume. In 2022, one fixture survived multiple PCB revisions specifically because it was designed to be boring. The probe map was conservative: stable nodes and must-catch defects, not an attempt to probe everything that existed on the netlist. The mechanical approach leaned on swappable plates and a base that stayed the same. When rev changes landed—connector rotation, a footprint swap, a regulator that moved—the team updated a small plate and relocated a handful of pins instead of waiting for a full tooling re-spin. In Tijuana, techs liked it because it made sense and could be serviced without calling the US at midnight.

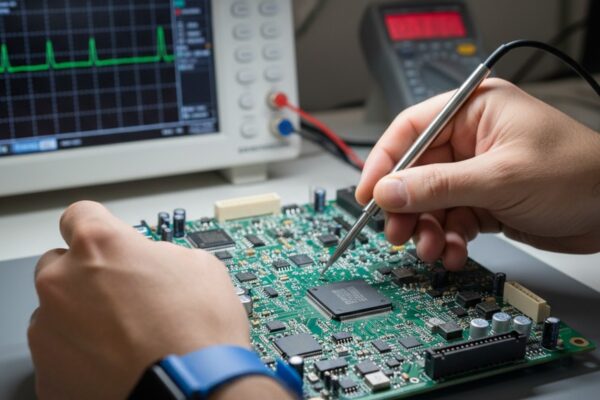

This is also where the DfT fight shows up. Someone will inevitably say, “We don’t have room for test points,” or “Can we probe vias?” or the classic, “We’ll add test points later.” The fixture world is not kind to those sentences. If a product is going to live in the 500–20,000 units/month band, test-point discipline is not a nice-to-have feature. Pads with reasonable size (the difference between a 1.0 mm target and a tiny exposed sliver), soldermask keepouts that don’t let pins skate, spacing that acknowledges real pin bodies, and ground references placed like someone actually plans to measure power integrity—those are what make “two-week fixture updates” possible instead of a recurring emergency.

A service model that can’t ask for test-point changes (or at least call out the consequence of not having them) is selling a fantasy.

Lead time is the next place teams get confused, so it’s worth being explicit about what’s uncertain. Fixture lead times vary wildly by vendor, region, and build type. A simple modular bed-of-nails can land in roughly a 1–3 week window in many real-world setups, while a heavy custom fixture or deep ICT program can drift into 6–10+ weeks, especially once shipping, customs, and revision churn enter the chat. Those are ranges, not promises. They’re also why a service relationship matters: if updates predictably cycle in about two weeks (plates, pin changes, docs), the team can plan builds instead of improvising.

That predictability is what teams are actually buying when they say they “can’t wait.”

Coverage That Matters, and the Maintenance That Makes It Real

There’s a question that shows up in customer questionnaires and internal KPI meetings: “What coverage percentage will this get us?” It sounds disciplined, but it can easily become coverage theater. A number can look impressive while missing the defects that actually cause line fallout and RMAs. Worse, the number never includes the fact that contact failures can turn “high coverage” into random failures that burn hours.

A better frame is brutally specific: what failure mechanisms will this catch, and which ones will it miss? Mid-volume programs have recurring pain patterns in MRB logs and RMA codes: swapped passives, rotated ICs, missing pull-ups, tombstones, solder bridges on fine pitch, cold joints on large connectors, wrong regulator BOM variant, ESD-damaged front ends. A minimum viable bed-of-nails strategy doesn’t try to be heroic. It aims to stop the dumb escapes now: rails present and in-range, continuity where it matters, critical analog nodes that reveal wrong-value parts, interface pins that can kill the system, and a handful of functional behaviors that expose timing and sequencing problems that a continuity-only approach will never see.

That’s also why “coverage tied to failure modes” beats “coverage tied to the netlist” in this part of the lifecycle. When a product is revving weekly, the cheapest fixture is the one that survives weekly. That often means choosing stable nets and building tests that map to known factory failures rather than chasing an abstract percent that will be invalidated by the next ECO.

And then there’s the part that a lot of teams learn the hard way: maintenance is coverage. A line in Mexico once started seeing intermittent opens on gold-finished pads. The failures moved around and didn’t reproduce consistently at the bench, which is how teams end up blaming silicon or assembly out of frustration. The root cause wasn’t exotic. The probe tip geometry was wrong for the pad condition, and spring force margins were thin for the stack-up. Once the team swapped to a better tip style and corrected the force profile, the “mystery defect” vanished. That episode is a reminder that pogo pins aren’t a checkbox. Tip selection, force, travel, and contamination tolerance are engineering choices, and they have to live inside a maintenance workflow that a CM can execute.

A fixture-as-a-service offering that doesn’t include pin kits, spares, inspection cadence, and a clear process for replacing worn probes isn’t really selling production test. It’s selling the first two weeks of production test.

What This Won’t Catch (and Why That’s Not a Secret)

A fast, minimum viable bed-of-nails approach will not catch everything. It can miss marginal behaviors that only show up under a rare load sequence or a narrow temperature band, and it can miss timing-dependent failures that only appear when the system is running “for real.” That’s not hypothetical. In 2016, a program shipped with a minimal test plan under brutal schedule pressure, and support later saw intermittent resets clustered in a specific temperature band. The root cause was a marginal power rail under an uncommon load sequence—something a more thoughtful functional check could have flagged before units shipped.

This is why a serious plan names its boundaries out loud. If the quick fixture is continuity-heavy, it should be paired with a small set of functional checks that exercise power sequencing and basic comms, even if the fixture arrives quickly. If the product risk is higher, the plan should say so explicitly, and the test investment should change accordingly. Probe life is also not a single number; datasheet cycle counts are optimistic baselines, and real life depends on pad finish, contamination, and force settings. The only reliable answer is a maintenance plan with inspection intervals and spares.

Speed is useful. Speed without explicit risk accounting is gambling.

Red-Team: The “Perfect ICT” Story, and the Boundary Conditions

The mainstream story goes like this: “Do it right. Build a full ICT program from day one.” For some products, that is absolutely correct. For many mid-volume commercial products, under time pressure and still dealing with ECO churn, it’s a trap disguised as quality.

The hidden costs aren’t philosophical; they’re operational. Lead time stretches. A heavy custom fixture becomes fragile to revision changes. Maintenance becomes a specialized skillset. Ownership becomes blurry between the OEM, the CM, and whoever built the fixture. The organization quietly becomes a fixture company. That might be acceptable if the volume is very high, the design is stable, and the product lifetime is long enough to amortize the effort. It’s much harder to justify when the board is still changing, the team is understaffed, and the build plan needs working test coverage in weeks, not quarters.

A staged approach is often the honest one: minimum viable bed-of-nails now, tied to real failure modes, with explicit upkeep and update cadence. Then, if volumes and stability justify deeper automation, move toward heavier ICT coverage or more elaborate fixturing. The 2022 “boring” fixture that survived multiple revs is the counterexample to the perfection story: it didn’t win a demo, but it kept production moving through churn, which was the actual goal.

When should this guidance be ignored? When liability and compliance dominate schedule. Medical and automotive assemblies, or anything IEC/UL compliance-critical where safety testing is not negotiable, change the risk calculus. Very high-volume products with a stable design and long lifetime can justify a heavier ICT program because the organization will actually own upkeep. Mature products where escapes are existential—brand-killing, recall-level—should not hide behind “minimum viable” as an excuse.

The point isn’t that ICT is bad. The point is that mid-volume teams need to be honest about lead time and ownership.

Buyer Field Notes: Don’t Outsource Responsibility by Accident

If a team is evaluating bed-of-nails fixtures “as a service,” the fastest way to get value is to force the service boundaries into the open, in engineering terms. The buyer should be able to answer: who provides the modular base and the replaceable plates? Who owns the pin ecosystem (tip selection, force assumptions, spares kits)? Who updates drill plates when ECOs land? The documentation pack matters: pin maps, plate drawings, a netlist/test-point layer reference from the CAD flow (Altium exports show up here often), and a maintenance SOP that a CM tech can execute mid-shift. Response time matters too: when yield drifts, what’s the escalation path, and what does “two-week update” actually include?

If those answers aren’t explicit, the team isn’t buying a service. It’s buying a box and a future argument.

For mid-volume products that cannot wait, schedule certainty comes from boring clarity: what is delivered, who maintains it, and how quickly it adapts when the PCB changes.