The Mathematics of Disappointment

The spreadsheet promised ten years. The marketing deck promised ten years. The engineering validation test units, sitting in an air-conditioned lab, are still humming along perfectly. Yet, out in the field—perhaps in a humid utility closet in Florida or an agricultural sensor network in the mid-Atlantic—the units are dying in six months. The batteries are flat.

When this happens, the instinct is to blame the energy source. You pull the logs, check the purchase orders, and convince yourself that the distributor sent you a bad batch of CR2032s. You assume the self-discharge rate was lied about, or that the temperature derating curve was optimistic.

It is almost never the battery. Modern lithium primary cells from Tier 1 vendors are remarkably consistent chemical engines. If they are empty, they didn’t leak the energy into the ether; they delivered it to a load. The catch is that the load isn’t your microcontroller or your radio. It’s the circuit board itself.

The Lie of “No-Clean” Flux

The culprit is usually a misunderstanding of the term “No-Clean.” In the world of high-speed digital electronics—think Raspberry Pis or laptop motherboards—”No-Clean” flux is a standard, safe material. It leaves a residue that is chemically benign enough not to short out a 3.3V power rail carrying amps of current. The impedance of that residue might be in the megaohms, which, to a CPU power supply, is effectively an open circuit.

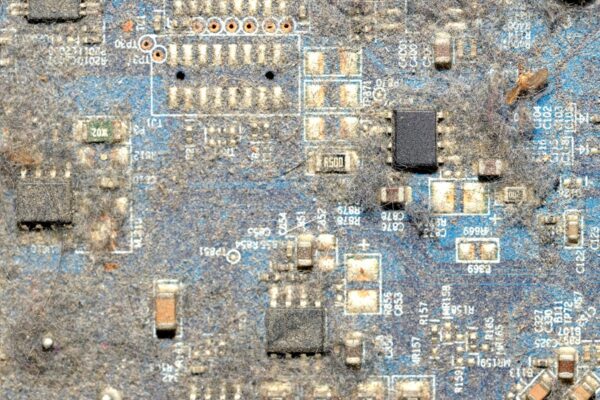

But you aren’t building a laptop. You are building an ultra-low power (ULP) device where the sleep budget is measured in nanoamps. In this domain, “No-Clean” is a marketing fabrication. The flux residue left behind by the reflow process is made of ionic activators—acids designed to chew through oxides on the copper pads to ensure a good solder joint. When the board comes out of the oven, that residue effectively hardens. But it isn’t inert. It is hygroscopic. It pulls moisture from the air.

As the humidity rises, that benign crust turns into a conductive electrolyte. We aren’t talking about a dead short. We’re talking about a “soft” short: a parasitic resistance sitting around 10 to 50 megaohms. In a mains-powered device, this is noise. In a device trying to sleep at 500nA, a 20 megaohm parallel resistance across your battery terminals or power switch is a catastrophe. It draws an extra 150nA continuously, 24 hours a day, regardless of firmware state. That invisible leak is what steals your nine and a half years of battery life.

There is a dangerous tendency to try and patch this with conformal coating. The logic seems sound: if moisture is the trigger, seal the board. But spraying urethane or acrylic over a board that hasn’t been aggressively washed isn’t a solution—it’s a tomb. You are simply trapping the ionic contaminants and the ambient moisture underneath the coating. The corrosion will continue, now protected from your attempts to clean it, and the dendrites will grow happily in their private greenhouse.

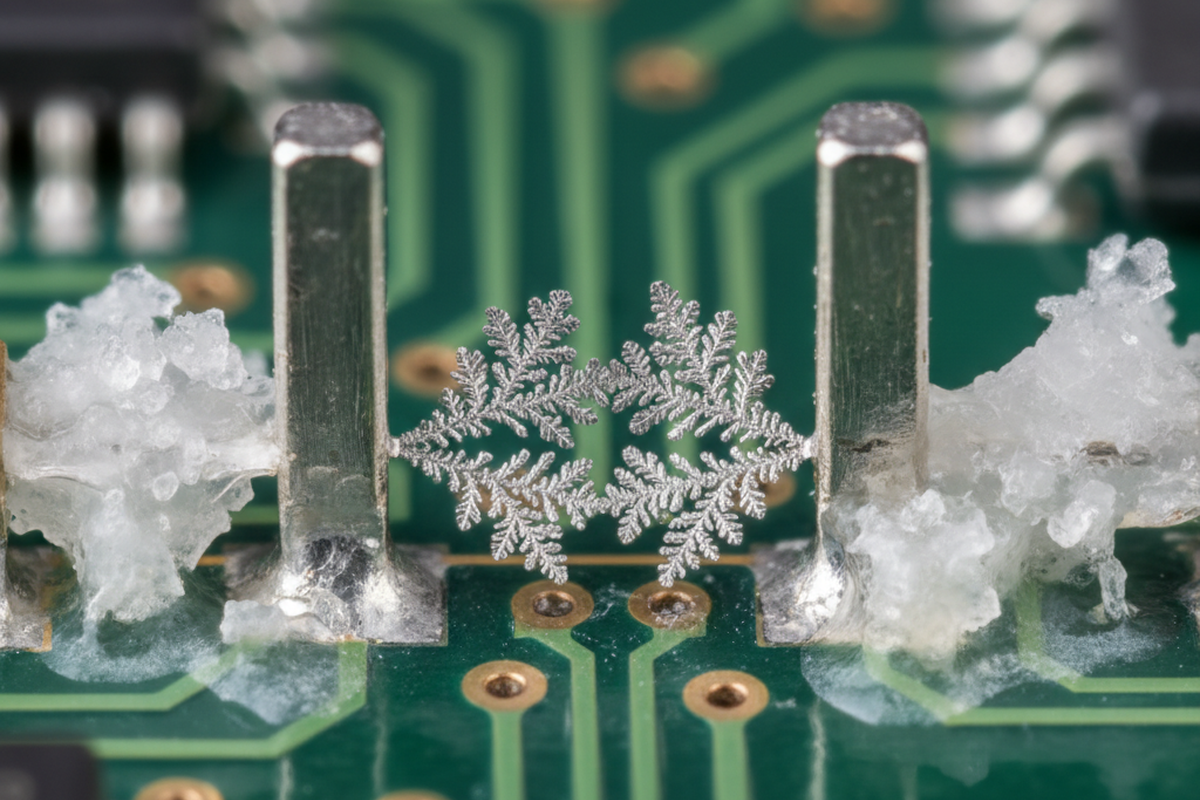

The Invisible Bridge: Humidity and Dendrites

The failure mechanism is rarely static. It breathes with the environment. This is why you cannot reproduce it on your bench in an air-conditioned office. The conductivity of flux residue is non-linear and chaotic; it spikes when the relative humidity crosses a threshold, often around 60-70%.

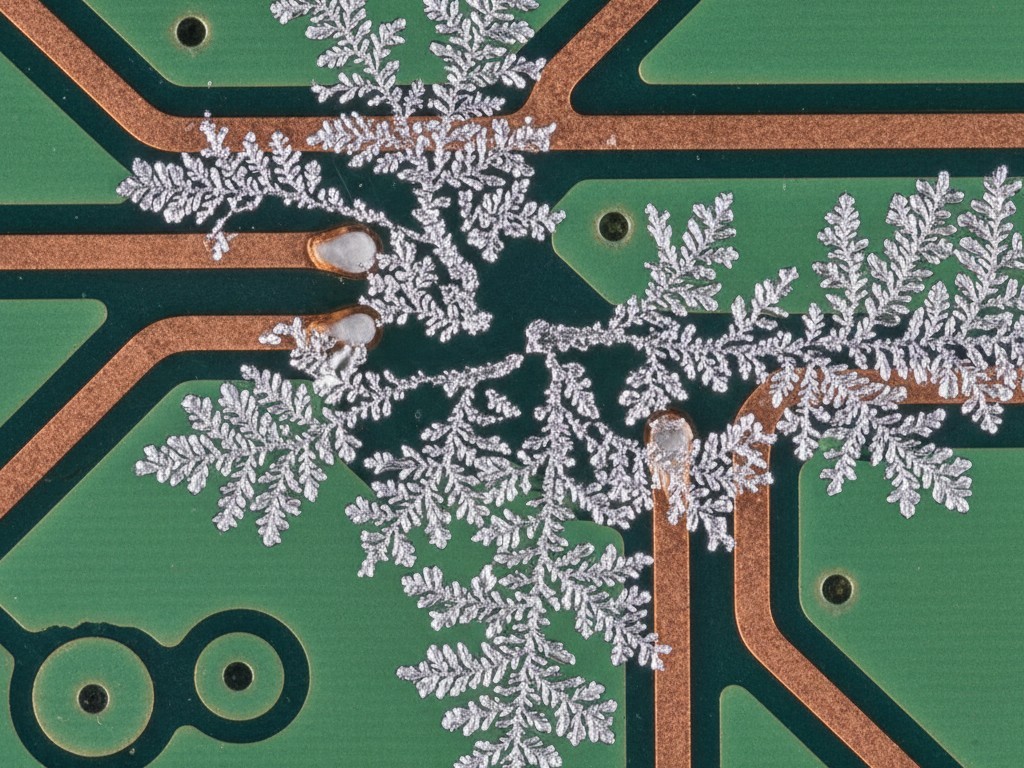

Consider a generalized case of a smart metering deployment. Units installed in climate-controlled server rooms last forever. Identical units installed in outdoor enclosures fail in clusters during the rainy season. Under a microscope, you can sometimes see the physical evidence: dendritic growth. These are fern-like metallic crystals that grow from the cathode toward the anode, fueled by the dissolved metal ions in the flux residue. They don’t need to bridge the gap completely to ruin you. They just need to reduce the insulation resistance enough to bleed the battery.

This migration is driven by the electric field. The tighter your layout—0402 components, 0.5mm pitch BGAs—the higher the field strength between pins, and the faster the migration occurs. The residue doesn’t need to be visible to the naked eye to be fatal. A monolayer of ionic contamination is enough to bridge two pads on a microcontroller, waking it up from deep sleep or simply bleeding current from VCC to Ground.

Your Multimeter is Lying to You

Part of the reason this failure mode persists is that standard engineering tools are blind to it. You cannot diagnose a 50nA leak with a Fluke 87V. Standard handheld multimeters have a burden voltage—an internal voltage drop—that disrupts the circuit you are trying to measure. Worse, they average out the current. They cannot see the dynamic nature of a leak that might be pulsing or drifting.

If you are debugging ULP battery life, you must use a Source Measure Unit (SMU) like a Keithley 2450, or at the very least, a specialized tool like a Joulescope. You need to see the floor. You need to verify that when your firmware says “sleep,” the current is actually flat. Often, with a proper instrument, you will see the “creep”—the current slowly rising over minutes as the board warms up or as the residue reacts to the environment. If you rely on a standard multimeter reading of “0.00 uA,” you are flying blind.

The Manufacturing Mandate

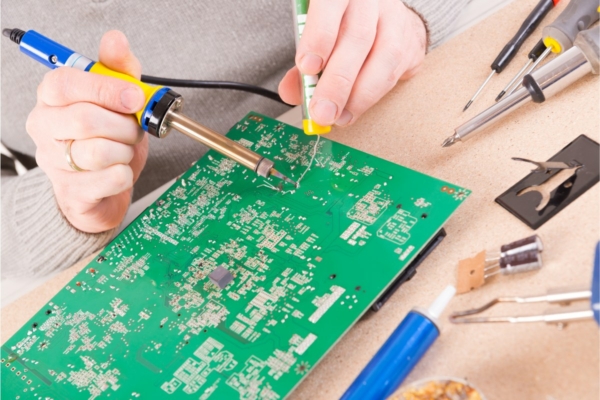

You won’t find the solution in firmware or a larger battery. You find it in the assembly house. Cleanliness must be treated as a design specification, not a manufacturing detail.

If you are building for a 10-year life on a coin cell, you cannot use a standard “No-Clean” process. You must mandate a wash. And not just a dip in a bucket of IPA—that just spreads the grease around. You need an in-line aqueous wash with saponifiers, followed by a DI water rinse, and a bake-out to remove the moisture.

This will be a fight. Contract Manufacturers (CMs) hate washing lines. They are expensive, require maintenance, and slow down the line. They will show you data sheets from the flux vendor claiming it passes IPC-J-STD-001. You must ignore this. Those standards are for general electronics, not for devices living on the edge of physics.

You must demand Ion Chromatography testing. You need proof that the board is chemically clean, not just visually clean. If the CM refuses, or tries to upsell you on a “better” No-Clean flux, walk away. The cost of a proper wash process is pennies per board. The cost of a truck roll to replace a dead unit in the field is hundreds of dollars. Do the math, and then force the wash.