There is a specific moment in every hardware startup’s life cycle where the balance sheet collides with physics. It usually hits during the transition from EVT (Engineering Validation Test) to PVT (Production Validation Test). You have a board that works. You have a contract manufacturer ready to ramp up. And then you see the quote for the test fixture: a $15,000 “Bed of Nails” (ICT) clam-shell that takes six weeks to machine.

The reaction is almost always the same. You look at the line item for “NRE” (Non-Recurring Engineering) and you balk. Why pay fifteen grand and wait a month when the factory has a machine right there on the floor that can test your board today for zero setup cost? It uses flying probes—articulated needles that zip around the board like a sewing machine, tapping test points one by one. No fixture, no wait time. It feels like a loophole in the laws of manufacturing economics.

It is not a loophole. It is a credit card with a 400% interest rate. While the flying probe is the savior of the prototype phase, relying on it for anything beyond a few hundred units is the single most common cause of production bottlenecks I see in the field. You aren’t actually saving money by skipping that initial capital expenditure. You are just moving the cost from a visible one-time check to an invisible, bleeding wound in your unit margin and schedule.

The Takt Time Wall

To see why the flying probe fails at volume, stop thinking about electronics. Think about time. Specifically, “beat rate” or takt time. If your Surface Mount Technology (SMT) line is humming along efficiently, it is likely spitting out a finished PCBA (Printed Circuit Board Assembly) every 30 to 45 seconds. That is the heartbeat of your factory. Every process downstream—inspection, testing, packing—must match that beat. If they don’t, you aren’t building a product; you’re building a pile.

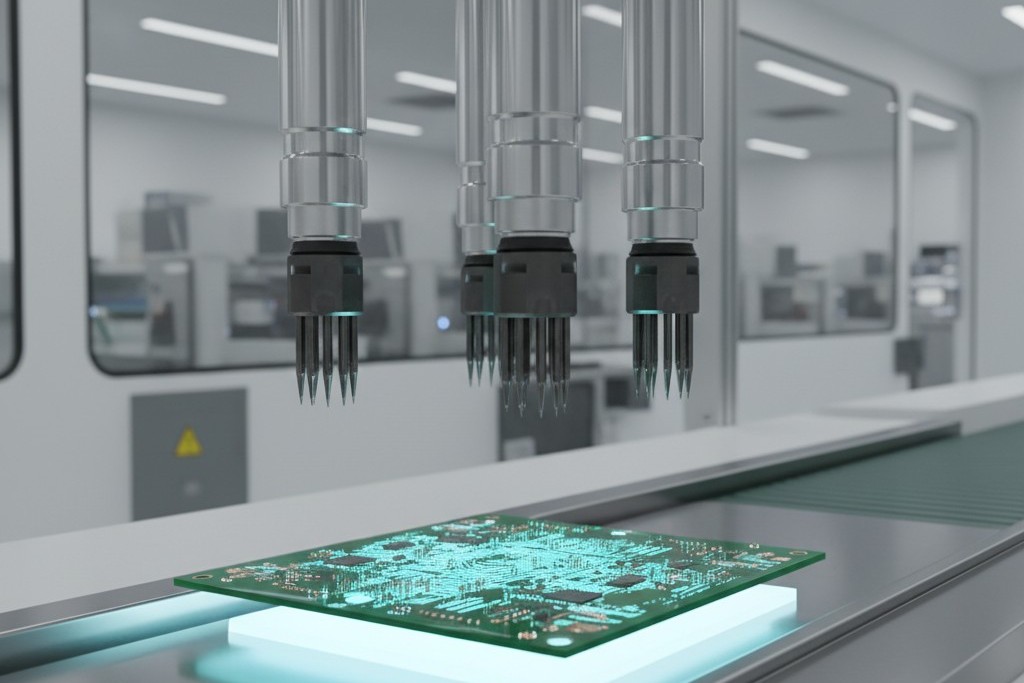

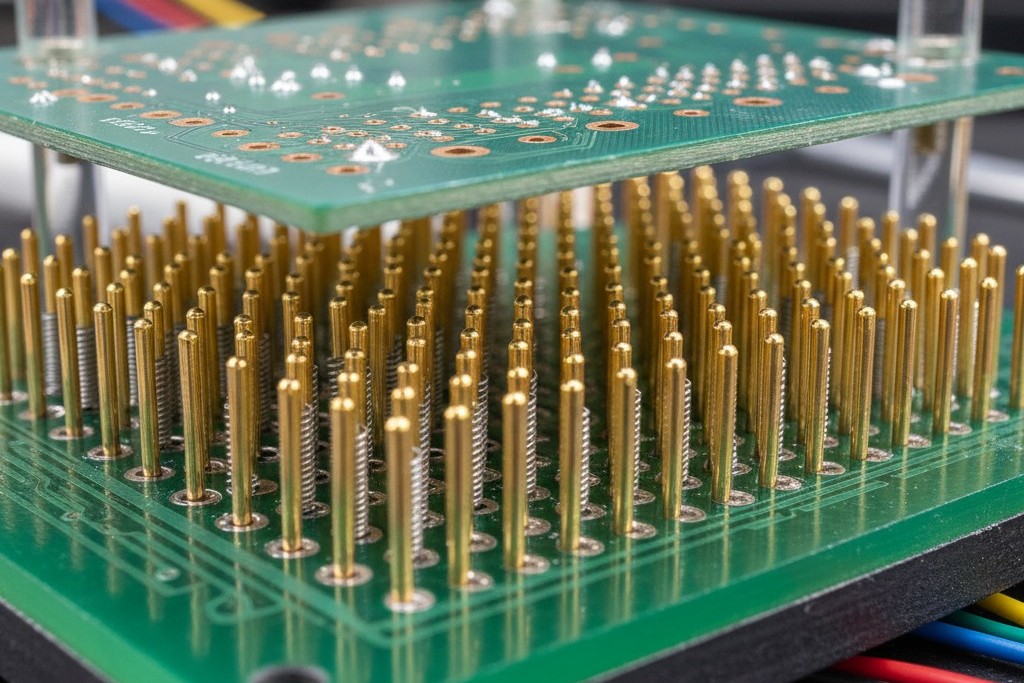

A bed-of-nails fixture tests a board by pressing 500 pins onto the PCB simultaneously. It checks every net in parallel. The test takes 15 seconds. Since that is faster than the SMT line, the belt never stops.

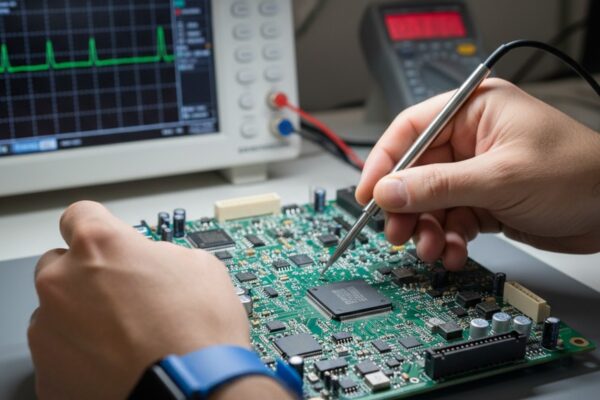

A flying probe tester, by contrast, is serial. It has four (sometimes eight) heads. To test those same 500 nets, it has to physically move, stop, descend, touch, measure, lift, and move again. Even with modern linear motors and high-acceleration gantries, physics imposes a limit. A moderately complex board with 400 nets might take a flying probe four minutes to test.

Do the math on that discrepancy. Your SMT line produces a board every 30 seconds. Your tester clears a board every 240 seconds. For every single board that clears the tester, seven more are piling up behind it. By lunch time on the first day of a 5,000-unit run, you don’t have a production line anymore; you have a warehouse storage problem. You have 400 untested boards stacking up in the hallway on anti-static carts.

I have seen production managers try to solve this by “just buying more machine time.” They run the probe 24 hours a day to catch up with an 8-hour SMT shift. They pay overtime. They beg the factory to put the boards on a second or third machine. Suddenly, that $15,000 you saved on the fixture is gone. You are paying for operator hours, machine depreciation, and electricity, amortized into the cost of every single unit. You are paying $5 or $10 per board for a test that should cost $0.50. You are burning margin to service a technical debt you took on to save a few pennies in week one.

Occasionally, a founder will ask if there isn’t some “universal fixture” or adjustable pin system that bridges the gap—something reusable that avoids the custom tooling cost but offers the speed. It’s a perennial dream, appearing in Kickstarter campaigns and trade show booths every few years. In practice, these adjustable systems are vaporware for high-reliability manufacturing. They lack the mechanical rigidity to hit 0.01-inch targets repeatably across thousands of cycles. You are stuck with the binary choice: the slow, flexible probe or the fast, rigid nail.

Physics, Friction, and False Fails

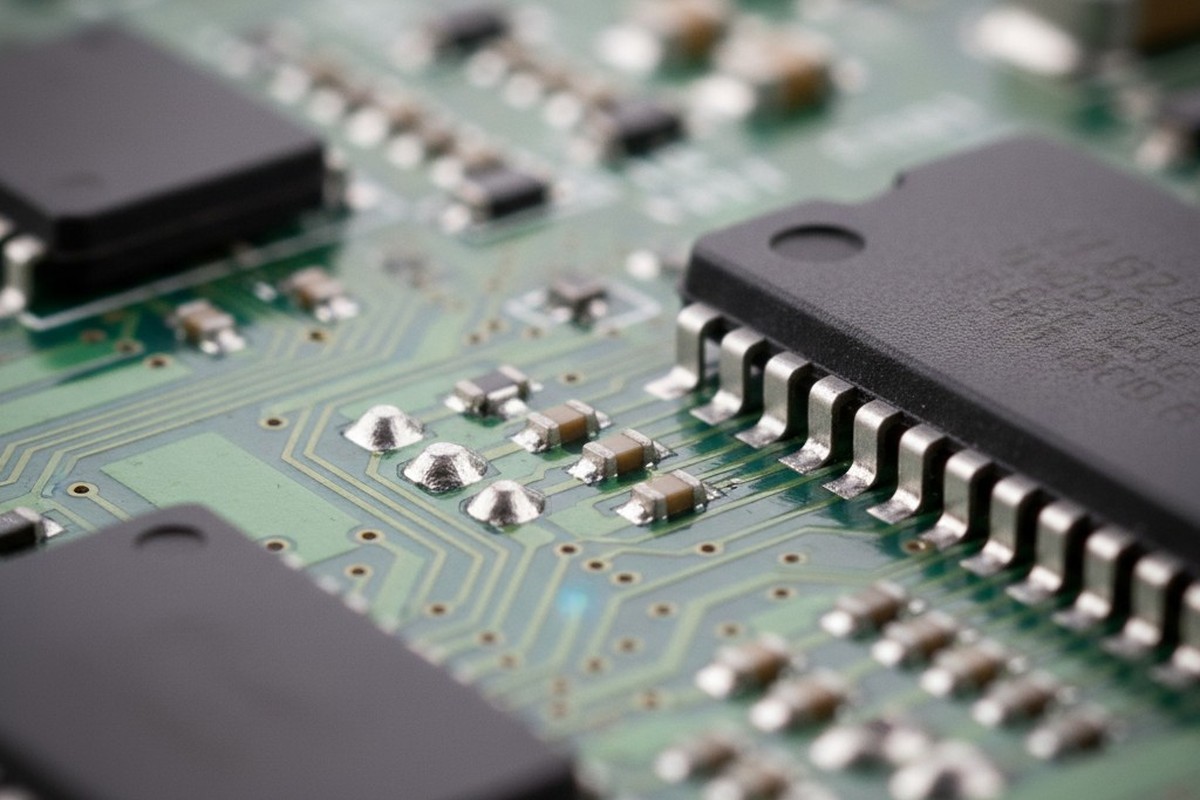

Speed isn’t the only enemy here. The other half of the problem is the fragility of the measurement itself. When you use a bed of nails, you have massive mechanical leverage. A pneumatic cylinder drives the board down with hundreds of pounds of force, crushing the probe tips through the oxidation and flux residue on the test pads to make a solid, gas-tight electrical connection.

A flying probe cannot do that. It is a delicate, balanced arm that taps the board gently. If your SMT process leaves a slightly thicker layer of flux residue on a test pad, or if a specific 0402 resistor is soldered at a slight angle, the probe tip might skid. It might land on the non-conductive solder mask instead of the pad.

The machine reports a “Fail.” The line stops. An operator walks over, looks at the board, wipes the pad with alcohol, and hits “Retest.” It passes. This happens ten times an hour. We call these “False Fails” or “Bonepile Noise.” In a bed-of-nails fixture, false fails are rare because the mechanics are brute-force. In a flying probe, they are a constant background radiation of inefficiency.

Every time the probe cries wolf, an engineer has to intervene. This creates a dangerous psychological effect: the “boy who cried wolf” fatigue. After the fiftieth false alarm on a 10k pull-up resistor, the operator stops investigating. They just hit retest until it passes. Eventually, a board comes through with a real missing resistor. The operator, conditioned by the machine’s flakiness, assumes it’s another glitch, forces a retest, or worse, manually passes the board. That bad board ships to the customer.

There is often a temptation here to bypass electrical testing entirely and rely on visual inspection systems—Automated Optical Inspection (AOI) or X-Ray. “If the solder joint looks good,” the logic goes, “the connection must be good.” This is a dangerous fallacy. AOI checks for the presence of a part and the shape of a fillet. It cannot see if a chip is internally dead. It cannot tell if a resistor is 10k ohms or 1k ohm. It cannot detect a cold solder joint that looks perfect on the surface but has no electrical continuity underneath. You cannot photograph electrons. You have to measure them.

When the Probe is King

Despite the throughput violence it inflicts on volume production, the flying probe is not obsolete. It is simply misunderstood. The probe is actually the king of two specific domains: the prototype and the “impossible” board.

When you are building Revision A of a new product, you are guaranteed to change the design. Buying a $15,000 hard-tooled fixture for a board that will be obsolete in three weeks is malpractice. Here, the flying probe is perfect. You load the CAD data, debug the program in a morning, and test your 50 prototypes. The cycle time is irrelevant because you aren’t waiting on 5,000 units.

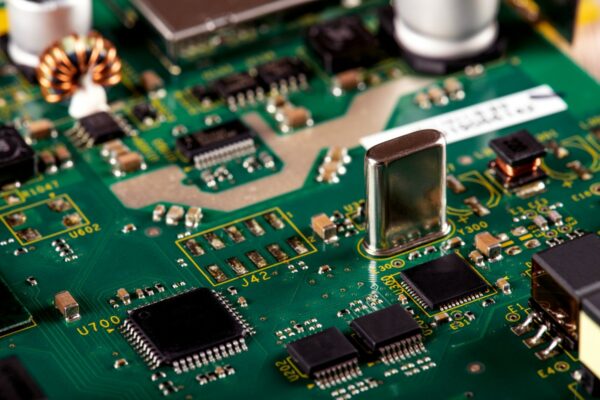

The second valid use case is the “Super-Board.” Consider a high-complexity server motherboard or a medical MRI controller. These boards might have 5,000 nets, 20 layers, and components on both sides so dense that there is literally no room to place a test point for a pogo pin. A bed of nails is physically impossible because you can’t fit the nails.

In these cases, the unit cost is often astronomical—$5,000 or $10,000 per board. The production volume might be five units a week. Here, a 40-minute test time is acceptable. The cost of the test time is a rounding error compared to the value of the board, and the volume is low enough that the tester isn’t the bottleneck. The flying probe’s ability to hit tiny vias and component legs becomes the only viable strategy.

The Crossover Strategy

The art of test strategy is knowing exactly when to fire your flying probe. The crossover point is rarely a hard number, as it depends on board complexity and the specific labor rates of your EMS provider. However, for a standard consumer electronics PCBA, the danger zone usually begins around 500 units.

If you are building 100 units, use the probe. If you are building 1,000, you need to run the ROI calculation. Compare the $15,000 fixture cost against the “adder” your contract manufacturer is charging for probe time. Often, you will find that the fixture pays for itself by unit #700.

But the calculation shouldn’t just be financial; it should be operational. Ask yourself: can I afford to have my entire supply chain throttled by the speed of a single mechanical needle? If the answer is no, pay the NRE. Build the fixture. Let the flying probe go back to doing what it does best: testing the prototypes of the future, not stalling the production of the present.