In 2014, a Tier 1 consumer audio brand faced a nightmare scenario on a factory floor in Penang. A trendy new headphone design had just ramped up production, featuring a main logic board packed with tight-pitch components. To pass a brutal drop-test specification, the engineering team had locked in a “concrete-grade” capillary underfill. This epoxy was so hard and permanent it essentially turned the board into a solid brick.

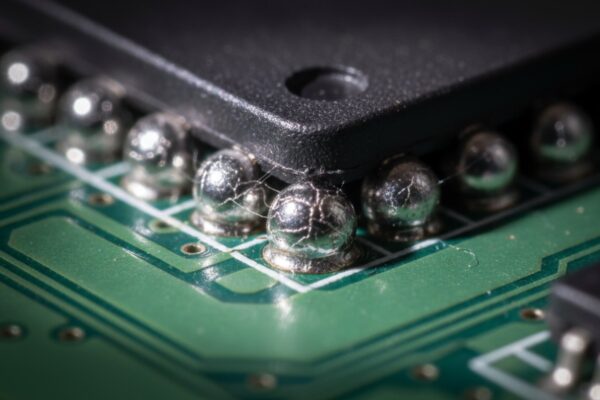

It worked beautifully for the drop test. But three weeks into production, the BGA vendor shipped a batch of chips with cold solder joints.

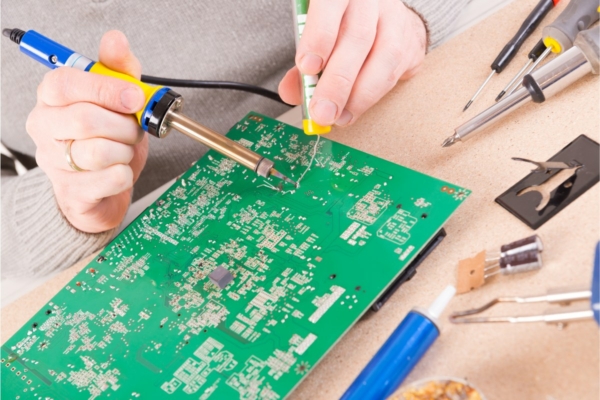

On a normal line, you’d rework these. You would heat the board, lift the chip, clean the pads, and place a new $4 component. But because of that specific underfill, rework was impossible. The epoxy bond was stronger than the laminate itself. Every attempt to remove the chip ripped the copper pads right off the fiberglass core. The factory had to physically destroy 12,000 fully assembled PCBAs—hundreds of thousands of dollars in inventory—because they couldn’t replace a single defective component.

This is the trap of treating underfill purely as a mechanical fix. It’s easy to view adhesive as a simple insurance policy against drop-test failures. But if you select materials based solely on survival metrics, you’re inadvertently designing a financial time bomb. When you specify a material that can’t be removed, you are betting that your manufacturing yield will be 100% forever. That is a bet no veteran engineer should ever take.

The Physics of Regret

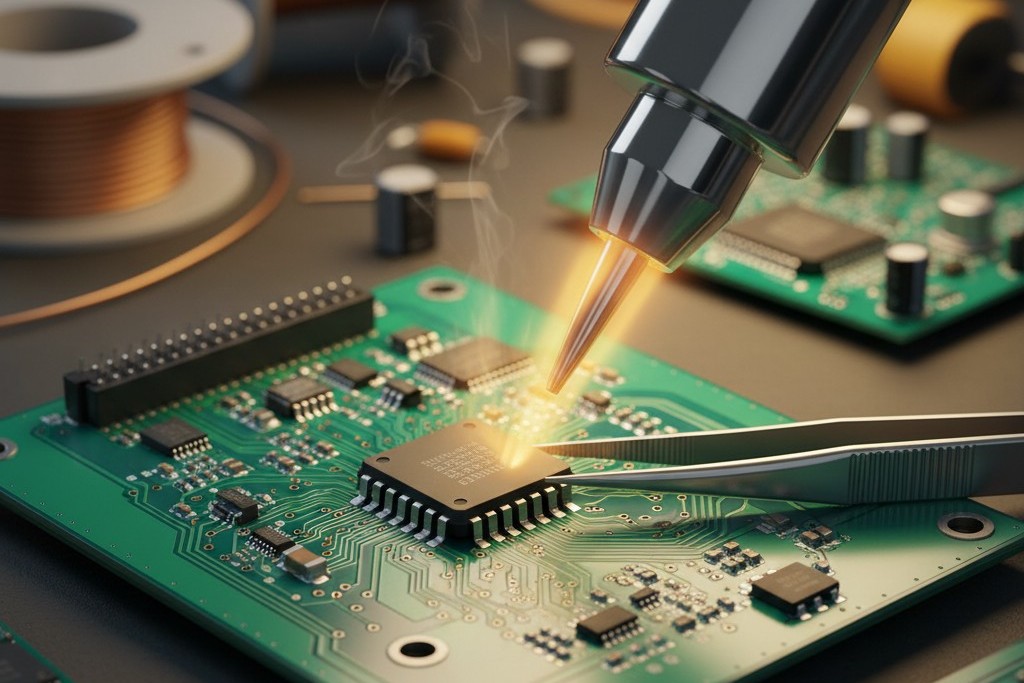

To choose the right material, you have to understand why you’re using it. Usually, the goal is to protect a Ball Grid Array (BGA) or Chip Scale Package (CSP) from mechanical shock. When a device hits the floor, the PCB bends. The stiff ceramic or plastic package of the chip doesn’t. That differential flexing creates massive shear force on the solder balls, cracking them. Underfill fills the gap between the chip and the board, coupling them together so they move as one unit.

However, “stronger” isn’t always better. A common mistake is selecting an underfill with a high Young’s Modulus (stiffness) and a high Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) that mismatches the solder. If the underfill expands much faster than the solder joints during thermal cycling—say, going from -40°C to 125°C in an automotive test—the glue itself can mechanically lift the chip off the pads. You are effectively installing a slow-motion crowbar under your components.

There’s also persistent confusion in the industry between structural underfill and conformal coating. You might see engineers asking if they can just “glob on” a thick layer of acrylic or urethane coating to secure a chip. They aren’t the same animal. Conformal coating is a thin barrier against moisture and dust; it has almost no structural integrity against the G-forces of a drop. Underfill is a structural engineering material designed to transfer load. Confusing the two is a fast track to field failures.

The goal isn’t to encase the chip in an invincible tomb; it’s to distribute stress away from the solder joints without introducing new thermal stresses that tear the assembly apart.

The Strategic Pivot: Capillary vs. Edge Bonding

For most consumer and industrial electronics, the default instinct is “Capillary Underfill” (CUF). This is the process where low-viscosity epoxy is dispensed along the edge of a chip, and capillary action sucks it underneath, filling the entire void. It provides maximum mechanical coupling. It is also the most difficult to rework.

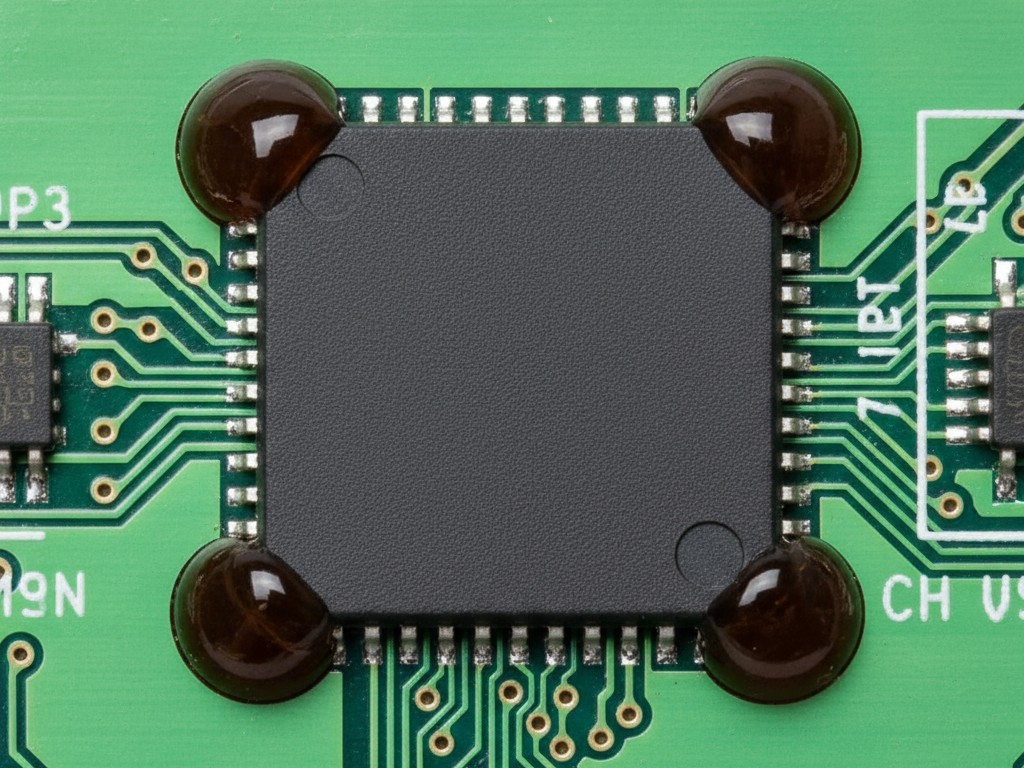

There is a superior alternative for many designs: Corner Bonding, or “staking.”

Instead of filling the entire gap, you dispense high-viscosity adhesive dots at the four corners of the BGA package. This anchors the chip to the board, preventing the corner solder balls (which always fail first) from taking the brunt of a drop impact. In a Design of Experiments (DOE) for an industrial IoT startup, we compared full capillary flow against corner bonding for a heavy FPGA. The full underfill survived 20 drops from one meter. The corner bond survived 18. Both exceeded the requirement of 10 drops.

The difference? When a firmware bug bricked the first 50 units, the corner-bonded FPGAs could be popped off and replaced in 15 minutes. The fully underfilled units would have been scrap. By sacrificing a tiny margin of theoretical durability, the client gained 100% serviceability.

A warning, however: Do not try to improvise corner bonding with whatever tube of glue is lying around the lab. I’ve seen engineers attempt to use RTV silicone (bathroom caulk, essentially) to stake components. Many RTV silicones cure by releasing acetic acid, which will eat through copper traces and corrode solder joints over time. If you are going to stake a component, use an adhesive specifically formulated for electronics—usually a non-conductive epoxy with a high thixotropic index so it doesn’t slump.

The One Spec That Matters: Tg

If you decide you must use full capillary underfill, your eyes should go immediately to one line on the datasheet: the Glass Transition Temperature, or Tg.

Tg is the temperature at which the epoxy transitions from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state. This is your rework window. To remove an underfilled chip without destroying the board, you need to be able to heat the adhesive above its Tg so it softens enough to yield, but keep the temperature below the point where the PCB laminate delaminates or the solder creates a thermal runaway.

A “Reworkable” underfill typically has a Tg around 80°C to 130°C. This allows a technician with a hot air station to heat the local area, soften the glue, and lift the chip. Non-reworkable, “structural” epoxies often have a Tg of 160°C or higher. By the time you get that material soft enough to scrape off, you’ve likely cooked the FR-4 board, lifted the copper pads, and destroyed the via structures.

Don’t trust the word “Reworkable” on the front of a vendor brochure. Every adhesive vendor claims their product is reworkable. What they mean is that it is reworkable if you have a $50,000 precision rework machine, eight hours of time, and the hands of a surgeon. Look at the Tg curve. If the material stays hard as a rock until 170°C, it is effectively permanent for any high-volume repair depot.

There is nuance here—reworkable formulations with lower Tg can be less stable over long-term aging in high-heat environments (like under the hood of a car). But for a tablet, a dashboard display, or a medical device, the trade-off is almost always worth it. I’m purposefully skipping the chemistry lesson on anhydride versus amine cure systems because, frankly, you don’t need to know the molecule shape to make the right decision. You just need to know if you can get it off the board.

The Scrap Math

Ultimately, underfill is an economic decision, not just a mechanical one. You need to run the “Scrap Math Audit.”

Take the cost of your populated PCBA. Let’s say it’s an $800 mainboard for a medical tablet. Now estimate the defect rate of your BGA component—perhaps 2,000 parts per million (ppm). If you use non-reworkable underfill, every single one of those 2,000 defects per million results in an $800 loss. You’re throwing away the CPU, the memory, the power management chips, and the board itself, all because one $5 chip had a cold solder joint.

In the case of the “Project Apollo” medical tablet fiasco in 2016, a non-reworkable underfill choice on a faulty memory chip led to the scrapping of 4,000 units. The loss wasn’t just the hardware; it was the logistics, the missed ship dates, and the warranty nightmare.

If you use a reworkable material or a corner-bond strategy, that failure costs you $50 in technician labor and a new component. The board is saved. Reliability isn’t just about whether the device survives the drop test; it’s about whether your business survives the manufacturing variance. Permanent implies perfect, and in electronics manufacturing, nothing is ever perfect.