The most expensive number on a connector datasheet is often the temperature rating. You see “260°C for 10 seconds” and assume safety. It suggests that if your reflow profile peaks at 245°C, you have fifteen degrees of headroom.

That is a dangerous fiction. That rating only guarantees the plastic won’t turn into a liquid puddle on the belt. It doesn’t promise the housing will remain flat enough to solder properly, nor does it account for the violent thermal tug-of-war happening between the connector body and your PCB.

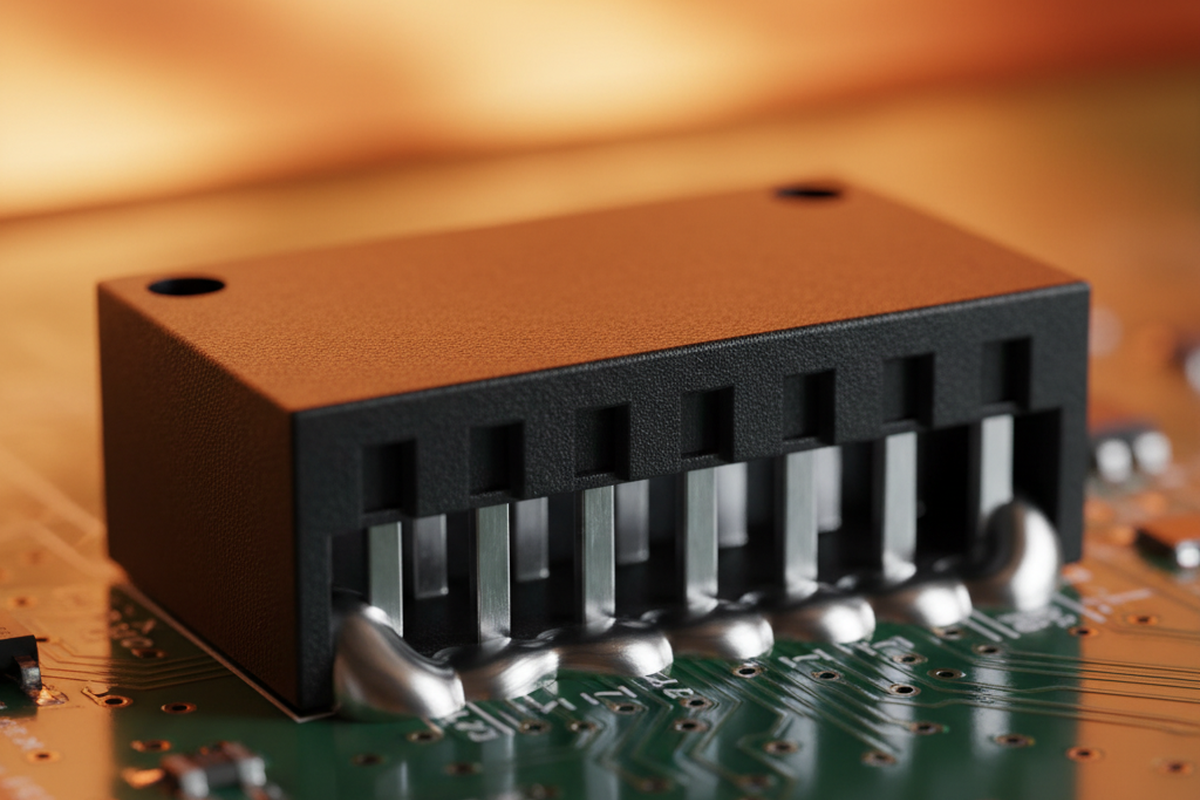

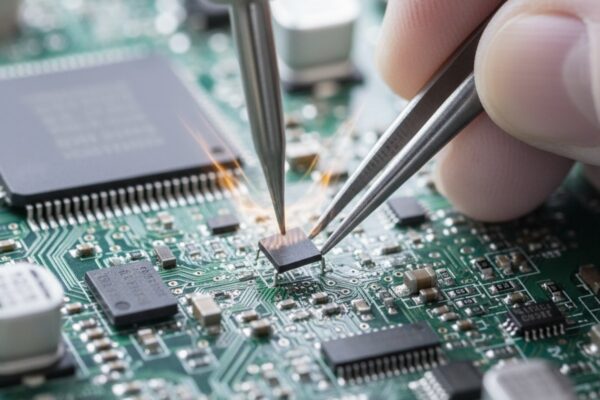

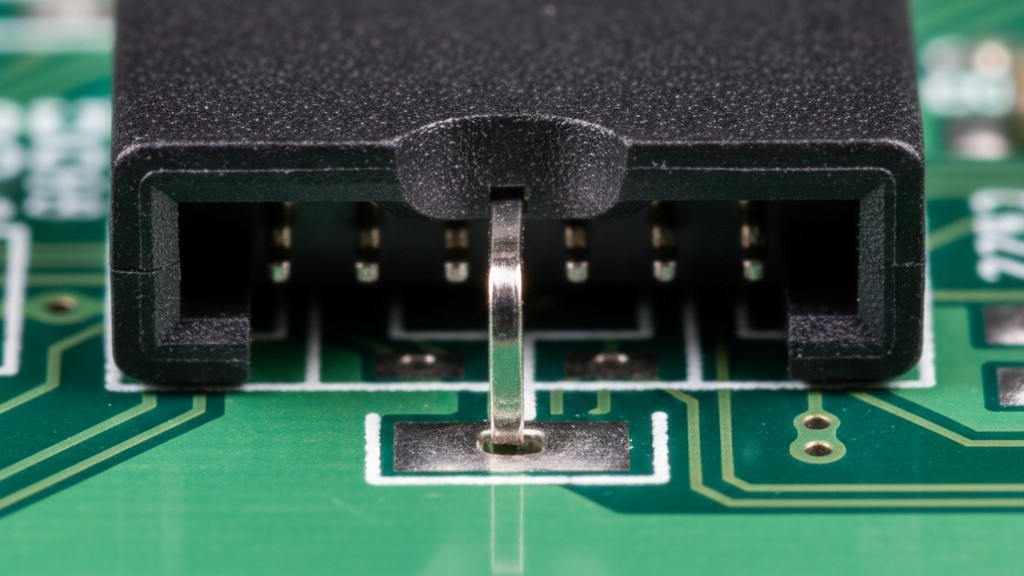

When a connector fails in the field—or worse, at the end of the line during In-Circuit Test—it’s rarely because the plastic melted. It’s because the housing warped, bowed, or twisted just enough to lift a pin off the pad. In the high-mix industrial world, we see this constantly: a pristine-looking connector testing as an “open” because the center pins are floating ten microns above the solder paste. The component didn’t melt, but it failed the physics of the assembly process. Understanding why requires ignoring the marketing bullet points and looking at the thermal mechanics of the materials involved.

The Physics of the “Banana” Board

Reflow isn’t just a heating process; it is a dynamic mechanical event. When a PCB enters the oven, the FR4 substrate begins to expand. As the temperature climbs toward the liquidus phase of SAC305 solder (around 217°C), the board grows in the X and Y axes. The connector sitting on top is also expanding, but almost certainly at a different rate.

This is the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) mismatch. If the connector is long—say, a 100-pin header or a PCIe edge connector—the difference in expansion between the plastic housing and the fiberglass board creates significant shear stress on the solder joints before they even solidify.

This stress reveals itself in the “banana” effect. If the board is thin (0.8mm or 1.0mm) and the connector is stiff, the board will bow to accommodate the connector’s refusal to expand. Conversely, if the board is thick and the connector housing is made of a less stable plastic, the housing will bow upward in the center, lifting the signal pins.

This is the root cause of the dreaded “Head-in-Pillow” defect. The solder ball melts and the pin gets hot, but they never merge into a single fillet because they were physically separated during the critical wetting phase. You can stare at x-rays all day blaming the stencil aperture, but if the plastic housing lifted the pin 0.15mm during the soak zone, no amount of solder paste tuning will fix the joint.

The Invisible Variable: Moisture

Even if you perfectly match your CTEs, a silent variable can still ruin coplanarity: water. Engineering plastics like Nylon (PA66, PA46) and Polyphthalamide (PPA) are hygroscopic—they love water. If a bag of connectors is left open in a humid warehouse for a week, those housings absorb moisture from the air.

When that moisture hits the 240°C spike of a lead-free reflow oven, the water inside the plastic doesn’t just evaporate; it flashes into steam. This internal pressure seeks an exit, causing micro-explosions within the polymer matrix.

In extreme cases, this manifests as visible blistering or “popcorning” on the surface. But the more insidious failure is a subtle warping invisible to the naked eye. The steam pressure deforms the flat seating plane of the connector, twisting it just enough to ruin the coplanarity specification.

This is why adherence to IPC/JEDEC J-STD-020 Moisture Sensitivity Levels (MSL) is not optional for connectors. If you use Nylon or PPA-based parts, they must be baked if their floor life is exceeded. Many assembly houses skip this step for connectors, assuming MSL ratings only apply to BGA chips. They are wrong, and that assumption leads to “mystery” yield fallout that vanishes the moment a fresh, dry reel is loaded.

The Material Hierarchy

Reliability eventually comes down to the resin. Not all “high-temp” plastics are created equal, and this is where the datasheet often hides the truth. The market is flooded with “modified” or “glass-filled” Nylons claiming high thermal resistance. While they may survive the oven without melting, their glass transition temperature (Tg)—the point where the material turns from a rigid solid to a soft, rubbery state—might be dangerously close to your operating or reflow temps.

Liquid Crystal Polymer (LCP) is the gold standard for a reason. It has an inherently low moisture absorption rate and, more importantly, a CTE very close to copper and FR4. It stays rigid and flat right up through the reflow spike. If you are designing a critical signal path or a connector with fine pitch (under 0.8mm), LCP is often the only responsible choice.

Polyphthalamide (PPA) is the common “budget” alternative. It is a high-temp nylon that performs well if it is dry. However, its dimensional stability is inferior to LCP, and it relies heavily on glass fill for stiffness. It is acceptable for power headers or larger pitch parts, but it introduces risk in fine-pitch applications.

Nylon 46 / 6T: These are legacy high-temp nylons. They are tough and cheap but act like sponges for moisture. You will see these on many generic connector clones. They often rely on the “Note 3” in the datasheet—small print limitations on the number of reflow cycles they can endure. Be wary of “bio-based” variants of these plastics entering the market; while sustainable, the long-term data on their stability in harsh industrial cycling (thermal shock) is still being written.

The cost difference between a generic Nylon header and an LCP version might be pennies. But you have to weigh that against the Cost of Poor Quality (COPQ). If a Nylon header warps and causes a 2% fallout rate on a $500 PCB, those pennies saved on the BOM just cost you thousands in scrap and rework labor.

Mechanical Defenses

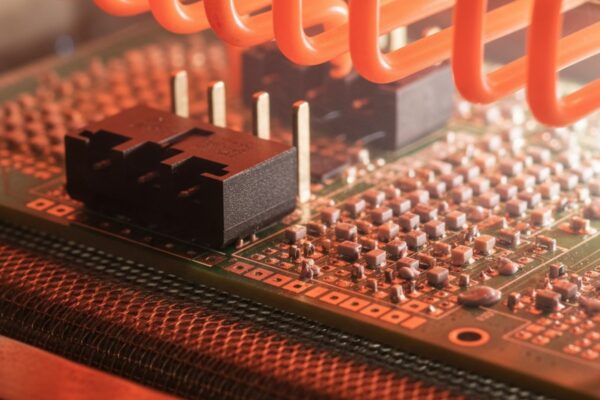

You cannot rely solely on the solder joint to fight mechanical forces. If a connector is tall or heavy, the leverage it exerts on the solder pads during vibration or thermal expansion is immense. SMT connectors purely held by signal pins are a liability in industrial environments. You need mechanical hold-downs—metal tabs or plastic pegs that anchor the housing to the PCB.

This is especially true if you are attempting a Pin-in-Paste (intrusive reflow) process, where through-hole connectors are reflowed. The paste volume calculation here is critical, but the mechanical stability of the housing during the oven ride is even more so. If the connector floats or tilts because it lacks hold-downs, you will end up with a skewed part that cannot mate.

For purely surface-mount parts, ensure your stencil design accounts for the “float” of the component. Sometimes, reducing the aperture on the center pads of a large connector can prevent the part from rocking on a cushion of molten solder, allowing the outer pads to seat firmly.

The Final Calculation

The goal of selecting a connector isn’t to find the cheapest part that fits the footprint. It’s to find the part that survives the brutal physics of manufacturing and the long haul of field operation. A datasheet rating of 260°C is a starting point, not a guarantee.

When you select a component, look at the material composition. Ask for the resin data. If the vendor can’t tell you if it’s LCP or Nylon 6T, walk away. The physics of thermal expansion and moisture absorption are undefeated. You can either respect them by choosing the stable material and the correct mechanical design, or you can pay for them later in the failure analysis lab.