The moment a return rate starts repeating within 90 days, nobody remembers the elegance of a lab report. They remember whether the next build shipped with the same defect.

That second wave is the real cost: not the first RMA, but the next shipment that quietly replicates it because everyone was “still analyzing.” A functional test yield chart with a sudden spike after a component substitution under shortage pressure isn’t an interesting plot; it’s a decision point. Usually, that decision is visible in the MRB minutes long before it shows up in a microsection.

The uncomfortable truth is simple: shipping while “not sure yet” is still a choice, and it has a predictable outcome when the mechanism is systemic.

There is a predictable pattern behind most messy, political failure-analysis spirals. It’s not that people lack microscopes. It’s that they lack a staged process that separates direction from certainty. The fastest loop is a disciplined one: 48 hours to triage and recommend containment, 5 business days to assemble an evidence pack that survives a meeting, and 15 business days (queues permitting) for a corrective-action package that lands in controlled documents. When someone says “the customer wants RCA in 24 hours,” what they actually need is language they can put in front of operations and the customer without overclaiming. They need to know what is known, what is suspected, what is being done right now, and what evidence would change the call.

The red-team move here is to challenge the mainstream reflex to stay silent until the root cause is proven. Silence forces shipping. Shipping multiplies scope. The alternative isn’t reckless certainty; it is scoped triage with confidence stated explicitly.

Intake Is Not Admin Work; It’s the Start of Evidence

Most “mystery” RMAs are just missing context disguised as technical complexity. The fastest way to waste a week is to start analysis on a unit that has no serial number linkage, no configuration state, and no record of post-failure handling. A crushed foam insert and a “DOA” note might look like carrier damage until someone notices a non-standard tape pattern, mismatched packaging insert part numbers, and pry marks that don’t fit the story. In that kind of case, the failure analysis isn’t on the PCB at all—it’s in chain-of-custody, returns handling, and repackaging. The corrective action might belong in a field service repack procedure rather than a factory work instruction. That only becomes obvious if intake forces the right artifacts up front: photos of the packaging and unit as received, plus a minimal RMA data sheet modeled on traceability fields (IPC-1730-style), even if customers hate forms.

A practical intake gate for pros is simple but non-negotiable: serial number, failure mode description, last known good state, firmware version, and environment notes that distinguish “how it failed” from “what you did after it failed.” If the organization is tagging returns in Zendesk (or any ticketing system), it quickly becomes obvious which fields are always missing (firmware version, humidity/chemicals, configuration). These missing fields map directly to “no fault found” rates. This is where the common NFF panic shows up: “We can’t reproduce it; it must be customer misuse.” Often, that is just a story the organization tells itself out of fatigue. Intake discipline is the cheaper alternative. Missing context creates the mystery; it also creates the arguments.

Intake has a hard limit worth stating plainly: once evidence integrity is compromised, it cannot be perfectly reconstructed later. That’s not moralizing. It’s physics and paperwork.

The 48-Hour Triage: A Decision System, Not a Vibe

Don’t treat 48-hour triage as a miniature root cause analysis. Its real job is answering a single question: “What should be different tomorrow morning?” The minimum viable triage system has a fixed sequence, because improvisation is how teams overfit to the first clue they like.

It starts with classification and integrity. Is the reported failure a hard fail, intermittent, cosmetic, or performance drift? Is the sample trustworthy—packaging intact, no obvious post-failure handling damage, chain-of-custody reasonable? Then come the minimal non-destructive checks that are fast precisely because they are scoped: visual inspection under a stereo microscope, power rail sanity, a basic functional attempt, and a quick thermal scan if it adds information without consuming days. The goal isn’t to “find everything.” It is to choose a path with stated confidence: likely manufacturing/process, likely design/interaction, or likely external handling/environment. That output matters because it drives who gets involved and what containment looks like. It also forces a separation between observations and hypotheses, which is the only way the report survives a room full of stakeholders.

The most useful triage deliverable is a single page that reads like a decision table: observations, ranked hypotheses, 2–3 decisive next tests, and a containment recommendation if the failure looks systemic or safety-relevant. The table must include confidence (low/medium/high) and it must be explicit about sample count. One unit does not represent a population, and pretending it does is how teams get humiliated later.

This is also where the “RCA in 24 hours” demand should be handled, not indulged. A triage statement can be fast and still defensible if it is framed as a staged commitment: within 48 hours, provide direction and risk framing; within 5 business days, provide an evidence pack; within 15 business days, provide a corrective-action package unless parts availability or destructive analysis queues block it. That structure gives operations and account teams something to say that is not a lie.

Once triage is working, it becomes obvious why some 8Ds fail. They jump from symptom to conclusion without building discriminating evidence. An automated SMT line does not have “operator soldering technique” as a meaningful root cause, but drafts like that happen because it feels satisfying and quick. The better path is to force the mechanism trace early: restate the symptom measurably, propose physical mechanisms (voids, cracks, corrosion, latch slip, threshold margin), list enabling conditions, and then identify observations that separate them. A defect spike aligned with a specific feeder lane and a solder paste jar lot is not a story; it is discriminating evidence. An AOI recipe masking a real defect mode is not a footnote; it changes the detection control. This is where supplier blame routing often goes wrong too. “Bad components” is a category, not a mechanism. If the question is attribution—component nonconformance versus assembly-induced damage versus system margin—the triage plan must include tests or artifacts that separate those bins.

A root cause that doesn’t change a control plan isn’t a root cause; it’s a narrative.

The evidence hierarchy is the guardrail that keeps triage from becoming theater. A professional failure analysis report labels what is observed (photos, logs, X-rays with settings, microsection images with cut location), what is inferred (hypotheses consistent with those observations), and what is concluded (only when evidence crosses a threshold). When these categories are mixed, the report becomes fragile. It collapses the moment a customer quality manager asks, “How do you know?” The fix is not better writing. The fix is better structure.

Containment Runs in Parallel (or You’re Just Watching)

Containment isn’t an engineering afterthought; it is a strategic product decision that buys time to prove a mechanism without multiplying risk.

The common failure mode is to treat containment as optional because “we’re still investigating.” That is backwards. If a critical failure mode exceeds a defined threshold in outgoing test—0.5% is a reasonable example for a serious mode in many contexts—it should trigger escalation to MRB within hours, not days. Containment can look like quarantine lots, targeted screening, or a ship hold with a scoped release plan, but it has to be explicit. It also has to be honest: containment actions are not root cause statements. A customer email that blurs the two may feel reassuring for a day and then become evidence against the organization when the story changes.

There is also a trap here for technically competent teams: “Let’s add more test.” More test is sometimes appropriate as containment or detection, but it is not a substitute for mechanism. Screening without mechanism turns into expensive filtering, and it tends to miss the activated failure mode anyway. Targeted screening can be smart when it is tied to a suspect axis—X-ray sampling on specific date codes, AOI program revision checks, torque verification on connectors, incoming inspection on a substitute regulator date code—but the point is to reduce shipped risk while the mechanism is being proven. It is not to pretend the mechanism is irrelevant.

Containment has constraints that cannot be hand-waved away. In regulated contexts—medical life-support, automotive safety cases—containment cannot mean bypassing validated processes or rushing uncontrolled rework. A controlled pause can be the safest option even when it is politically painful. This is exactly why containment should be treated as a leadership decision supported by receipts: yield by lot, failures by shift, correlation to a change notice, and a clear explanation of what is being held, screened, or released.

X-ray Isn’t a Verdict. Microsection Isn’t a Hobby. Certainty Has a Price.

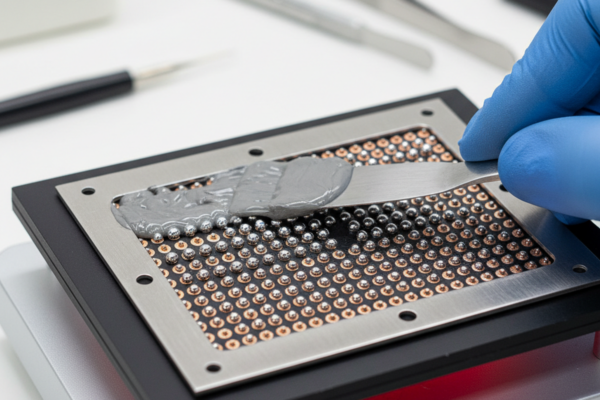

X-ray is one of the most misused tools in RMA triage because it produces images that look like answers. A 2D/oblique system—Nordson DAGE Quadra 7 class tools are a representative example—can be extremely effective if the method is disciplined. You must document kV, angle, and fixturing so images are comparable, and treat the result as a routing artifact, not a conviction. If the X-ray suggests possible interface anomalies under BGA corners but cannot confirm head-in-pillow or intermetallic separation, the correct output is not “solder defect confirmed.” The correct output is: “X-ray suggests an interface anomaly; destructive confirmation required.” That phrasing sounds less satisfying, but it survives scrutiny.

This is where the “Do we even need cross-section?” question lives. Cross-sections are expensive—often on the order of $450–$900 per location at common third-party labs—and turnaround can be 3–7 business days depending on queue. But they end arguments when they are scoped to a question. They can turn a week of blame ping-pong into an implementable control plan change tied to a stencil revision, a reflow profile window, or a paste handling limit. That is the real ROI: not the image, but the end of the debate.

X-ray also has a technical uncertainty that professionals should name out loud. Interpretability varies with settings and operator habits; grayscale is not a universal truth. “Looks fine” does not mean “is fine,” especially for fine cracks, certain delamination modes, or interface issues that evade 2D contrast. Microsection has uncertainty too, and it is different: sample prep can induce artifacts, and cut location can bias conclusions. A credible report states the rationale for cut locations and, when stakes justify it, uses multiple cuts to avoid overfitting a localized observation.

The supplier-blame question often shows up here in a sharp form: “Is it the supplier’s fault?” The disciplined answer separates component nonconformance from assembly-induced damage and from system margin. A case where MLCC leakage current appears sporadically can look like a component defect until microsectioning and focused SEM/EDS (with methods clearly stated) show cracking consistent with board flex during depanelization. That outcome doesn’t “let the supplier off the hook” as a favor; it prevents the organization from spending money on the wrong corrective action. It also shows why the right destructive cut is not overkill: it is how the ecosystem stays stable while the mechanism gets fixed.

NFF and Intermittents: If the Lab Can’t Trigger It, the Stressor Is Missing

“No fault found” doesn’t work as a conclusion. Instead, treat it as a symptom of the gap between field conditions and lab assumptions.

Intermittent failures almost always have an activation stressor the lab is not replicating. The fastest way to find it is not to rerun the same bench test harder. It is to reconstruct the field stressor with a structured script: what happened right before failure, mounting and vibration environment, cable lengths and routing, cleaning chemicals, humidity, thermal conditions, and what changed in firmware or configuration. Field tech logs and videos are not “soft” data when they show a compressor kick cycle or a long cable run; they are often the missing variable. A reset storm that clusters after a firmware update and only on installations with 30–50 m cable runs isn’t a weird story. It points directly at an interaction between power integrity and sequencing, and it tells the lab what to simulate: added cable inductance, noisy supply conditions, and a supervisor threshold margin that might be fine in the lab and marginal in the field.

There is unavoidable uncertainty here, and it should be handled with competing hypotheses rather than vague hedging. Intermittents can be multi-factor. The professional move is to state what is being tested, what would falsify the current hypothesis, and what evidence would cause the conclusion to change. Treat the inability to reproduce as information: either the stressor is missing, the sample is compromised, or the mechanism is truly rare and needs sample size.

A practical intake-and-reconstruction bridge is a small set of questions that are asked every time and then actually used: firmware version and delta, environment signature, installation photos, cable lengths and grounding, and whether the unit was opened or repacked before return. Rather than looking for ways to blame the customer, the goal is to stop treating NFF as a dead end and start treating it as a data-collection failure.

Corrective Action That Actually Closes the Loop

The fastest way to tell whether an RCA is real is to ask a question that makes everyone slightly uncomfortable: which controlled artifact changes Monday morning?

If the answer is “we’ll remind people” or “we’ll be more careful,” the loop is not closed. If the answer is “operator error” on a fully automated SMT line, the loop is actively being dodged. Convenient stories are emotionally satisfying because they feel like closure. They are also cheap, which is why they recur.

Corrective action that prevents recurrence has a specific shape. It assigns owners and due dates, but more importantly it forces the action to live in a controlled system: an ECN/ECR for design changes, a PFMEA line item and Control Plan revision for process and detection controls, a Work Instruction revision for the step that operators actually perform, a Supplier SCAR when supplier controls truly need to change, and a test specification update when coverage is the lever. An 8D that cannot map D4 to one of those artifacts is not finished, regardless of how confident the narrative sounds.

This is where the “add more test” instinct should be red-teamed again. Testing is a filter. It can be an effective containment or detection control, but it rarely fixes a mechanical stress mechanism or a system margin interaction. If the mechanism is board flex cracking MLCCs during depanelization, more electrical test does not remove the stress; tooling and process changes do. If the mechanism is a design margin issue exposed by a component substitute, a screening test might catch failures, but the durable fix lives in design choices, approved alternates, and updated specifications that reflect the margin reality.

Supplier attribution belongs in the same disciplined frame. “Bad batch” is not a corrective action. A supplier control change might be appropriate, but the evidence has to distinguish component defect from assembly-induced damage. Otherwise the organization spends political capital and money on a supplier switch while the assembly mechanism persists.

A simple mechanism-to-control translation that closes loops looks like this: restate the symptom in measurable terms; translate to a physical mechanism candidate; list enabling conditions; identify discriminating observations; and convert the mechanism into a control that can be audited. Then define verification and an escape check. Verification might be outgoing yield improvement, a bend in the RMA curve, or screening results by lot. Escape checks are what prevent regression under future substitutions or process drift: periodic sampling, audit points, or controlled recipe verification. A 30/60/90-day check tied to actual production builds is not bureaucracy; it is how “fixed” becomes durable.

What Good Looks Like (and When to Stop Digging)

A good failure analysis output is not a novel. It is an evidence pack that drives decisions and can be re-opened months later without changing its story. The contents are usually boring and therefore powerful: photos, X-ray images with settings documented (XRY-03 style artifact IDs are enough), test logs, lot traceability, microsection images with cut locations (SEC-02), a timeline of changes, and a one-sentence annotation for what each artifact proves and what it does not. It also includes a stop rule. When evidence is sufficient to select a corrective action that will change a controlled artifact and reduce risk, the organization should stop digging for a more satisfying story.

There are legitimate reasons to stay provisional: sample count too low to sacrifice a unit, compromised chain-of-custody, or an intermittent failure that still cannot be activated. In those cases, the correct move is to label uncertainty explicitly, run containment that matches the risk, and continue collecting the right samples rather than collecting more opinions.

What closes the loop fast isn’t heroics. It is staged decisions, receipts that survive meetings, and a corrective action that lives in a document somebody controls.