You’ve likely stood on a production floor, looked at a tray of freshly minted PCBs, and thought they looked perfect. The solder joints were bright and shiny. The fillets met IPC-A-610 Class 3 visual criteria. The quality manager even handed you a report saying the batch passed the cleanliness test. And yet, three months later, those same boards are coming back from the field dead, erratic, or draining batteries three times faster than the spec sheet allows.

This is the central paradox of modern electronics manufacturing: a board can be visually flawless and “compliant” with industry standards, yet chemically destined to rot.

When a high-reliability system fails intermittently—the kind of “No Fault Found” returns that evaporate on a bench test but reappear in humid environments—the culprit is rarely a broken trace or a bad chip. It’s almost always invisible. It is ionic contamination trapped in the shadows of the board, underneath components where no human eye or camera can see. You aren’t fighting a traditional manufacturing defect. You’re fighting physics. And if your strategy relies on visual inspection or bulk cleanliness averages, physics is going to win.

The Physics of Leakage

To understand why these failures happen, you have to stop thinking about “clean” as an aesthetic quality and start thinking of it as an electrical specification. Flux residue, the byproduct of the soldering process, isn’t just dirt. It’s a chemical cocktail that, under the right conditions, becomes conductive.

The mechanism is simple and brutal. Most modern fluxes are designed to be “no-clean,” meaning their residues are supposed to be benign. In a dry, climate-controlled server room, they often are. But flux residue is hygroscopic; it absorbs moisture from the air. When you combine that moisture with the ionic salts in the residue and apply a voltage bias across it, you create an electrolytic cell.

Current leaks. It might start in the nano-amp range—too small to trigger a hard short, but enough to wreak havoc on sensitive circuits. If you’re designing an IoT device or a medical implant, this is where your power budget goes to die. You might blame the battery vendor because your device lasted six months instead of two years, but the battery was fine. The board was simply consuming a parasitic load through a conductive film of wet flux, slowly bleeding the system dry.

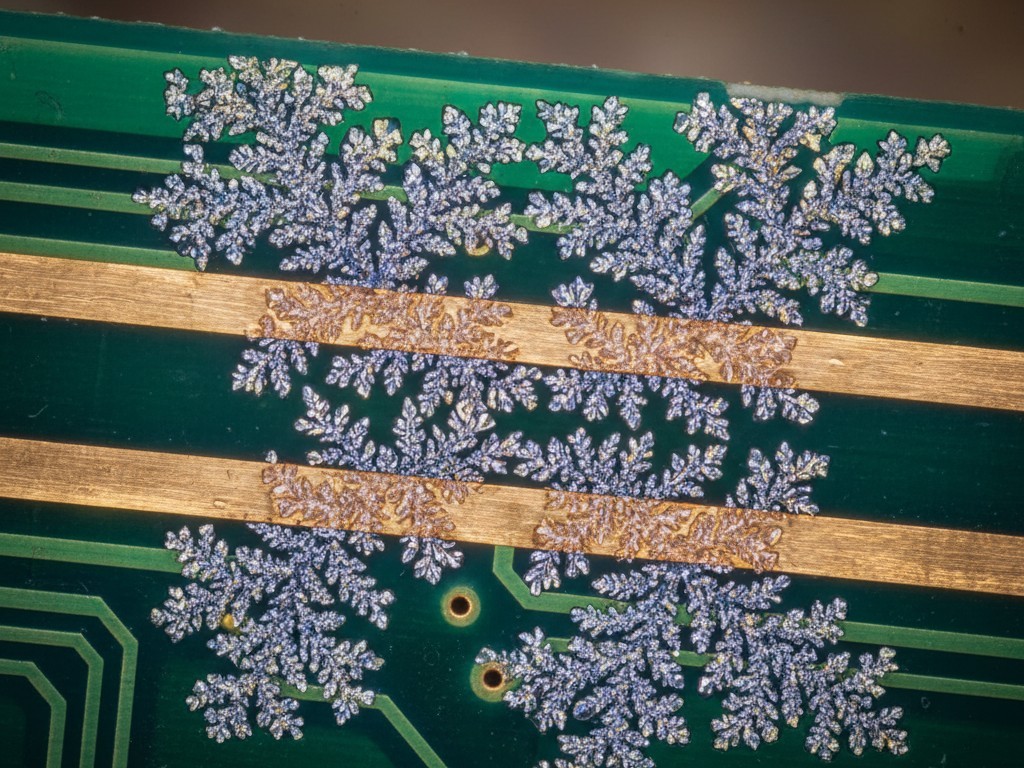

In more aggressive scenarios, this leakage evolves into electrochemical migration. Metal ions dissolve at the anode and migrate toward the cathode, plating out in fern-like structures called dendrites. I’ve seen these dendrites grow underneath conformal coating in high-voltage sensors used on oil rigs. The engineers thought the coating would protect the board, but they had coated over a dirty surface. The coating didn’t seal the moisture out; it trapped the ionic contaminants against the board, creating a pressurized greenhouse for dendritic growth. Eventually, the coating delaminated, bubbling up as the reaction released gas, and the sensor shorted out. Coating isn’t a band-aid for a dirty process. If the surface isn’t chemically neutral first, coating is just a force multiplier for failure.

The Fallacy of Averages (Why ROSE is Dead)

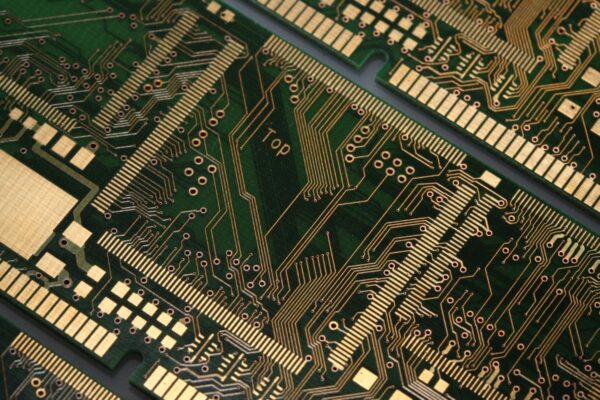

For decades, the industry relied on the ROSE (Resistivity of Solvent Extract) test to catch these problems. You dip the board in a solution, measure the change in resistivity, and get a number representing the average cleanliness of the assembly. If it’s below 1.56 µg/cm² of NaCl equivalent, you pass.

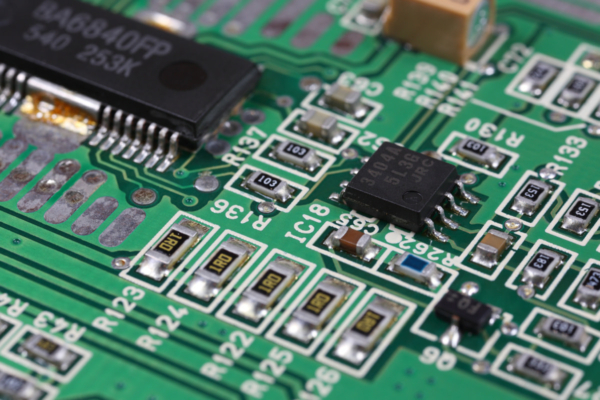

This method is a dinosaur. It was developed for through-hole technology where components were large, spacing was generous, and cleaning fluid could easily flush the entire surface. Applying ROSE to a modern high-density board populated with QFNs (Quad Flat No-leads) and 0201 passives is worse than useless; it’s dangerous.

Look at the geometry. A ROSE test averages the contamination across the entire surface area of the board. You could have a pristine board with zero contamination almost everywhere, but a massive concentration of active flux trapped under a single 48-pin QFN. Because the test averages that spike across the whole board, the final number looks low. You get a “Pass” on the report. Meanwhile, that QFN is sitting in a pool of halides, waiting for the first humid day to short out.

The standard limits are often grandfathered in from an era of much lower sensitivity. A value of 1.0 µg/cm² might be fine for a toaster, but for an automotive radar operating at high frequencies, or a pacemaker sensing micro-volt signals, it’s catastrophic. Relying on a bulk average to certify a high-density design is like checking the average temperature of a hospital to determine if one patient has a fever. It masks the local reality.

Localized Forensics: The Only Truth

If you can’t measure contamination locally, you’re guessing. To ensure reliability in ultra-low leakage designs, you must move from bulk averaging to localized forensics using tools like C3 (Critical Cleanliness Control) or localized Ion Chromatography (IC).

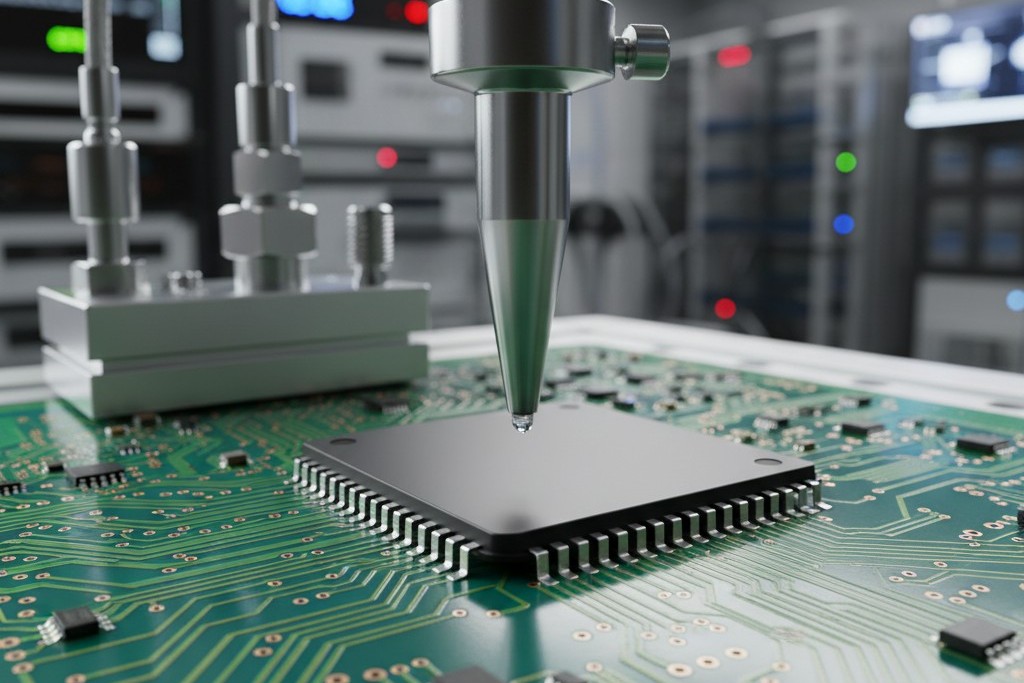

The process is surgical. Instead of washing the whole board in a bucket, these systems use a small nozzle to dispense a precise volume of extraction fluid onto a specific component—say, that suspect QFN or a tight cluster of BGAs. The fluid sits there, dissolving the residues trapped between the pads, and is then sucked back up and analyzed.

The results are often shocking. I’ve audited production lines where the bulk ROSE test showed a comfortable 0.2 µg/cm², but a localized extraction on the power management IC revealed levels closer to 15 µg/cm² of sulfate and bromide. That’s the smoking gun. That’s the difference between a reliable product and a field recall.

You also need to verify the future, not just the present. This is where Surface Insulation Resistance (SIR) testing comes in. SIR uses test coupons with comb patterns designed to mimic your board’s geometry. You subject these coupons to heat, humidity, and voltage bias for weeks (often 500+ hours). If the resistance drops, you know your process—flux, wash, and bake—is creating a conductive path.

When analyzing these results, you aren’t hunting generic “dirt.” You’re looking for specific ions. Chlorides and bromides are the aggressive killers usually sourced from flux activators. Sulfates often come from tap water rinsing or cardboard packaging. Sodium might come from human sweat. Knowing what is on the board tells you where the process broke down.

The Chemistry of Regret

Solving this often requires a tough conversation about “No-Clean” fluxes. The marketing term “No-Clean” is one of the most successful deceptions in electronics history. It implies “leave it alone and it will be fine.” A more accurate name would be “Low-Residue, High-Risk.”

For consumer toys or standard digital logic in dry environments, “No-Clean” is perfectly adequate. But for high-reliability, low-leakage circuits, that residue is a liability. The problem is that you can’t just rinse a “No-Clean” board with water. These resins are designed to be water-insoluble. If you wash them with pure DI water, you often don’t remove them; you just partially dissolve the carrier and leave behind a white, conductive sludge that is far worse than the original residue.

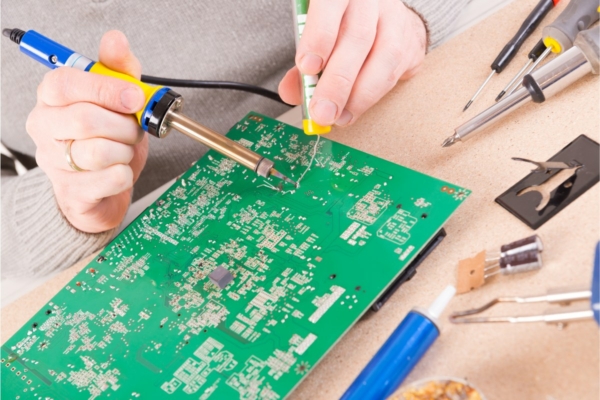

To clean a modern board, you need chemistry. You need saponifiers—engineered cleaning agents that react with the flux residue to make it water-soluble, allowing it to be flushed out from under those low-standoff components. You have to fight the geometry trap. If a component has a standoff height of 25 microns, water with its high surface tension (72 dynes) will struggle to penetrate that gap. You need a cleaning fluid with lower surface tension and a wash process that adds mechanical energy (sprays or ultrasonics) to force the fluid in and, crucially, drag the waste out.

Reliability is a Choice

There’s always a voice in the room that argues against this. They’ll say localized testing is too slow, or that adding a wash cycle with saponifiers costs too much. They’re doing the math wrong.

They are calculating the cost of the fluid and the machine time. They are ignoring the cost of the reputation hit when your flagship product fails in the tropics. They are ignoring the cost of flying engineers to a customer site to troubleshoot a “phantom” error that vanishes when the AC is turned on. Physics doesn’t negotiate with your production schedule. If you leave ions on the board, and you give them a path and a bias, they will move. The only choice you have is whether you remove them before the board leaves the factory, or wait for them to kill the product in the customer’s hands.